OCT 16 — Lawyer Datuk Rosli Kamaruddin on Monday (Oct 14) questioned why the police were invoking the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (Sosma) to detain Global Ikhwan Service and Business Holding (GISBH) members when the law was specifically created to allow the government to tackle terrorism.

The short answer is in Section 2 Sosma which says that the “Act shall apply to security offences”.

The term “security offences” is defined to include not only offences relating to terrorism (Chapter VIA of the Penal Code), but also offences against the State (Chapter VI of the Penal Code), organised crimes (Chapter VIB the Penal Code), and offences under the Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007 (Atipsom) [Section 3 Sosma].

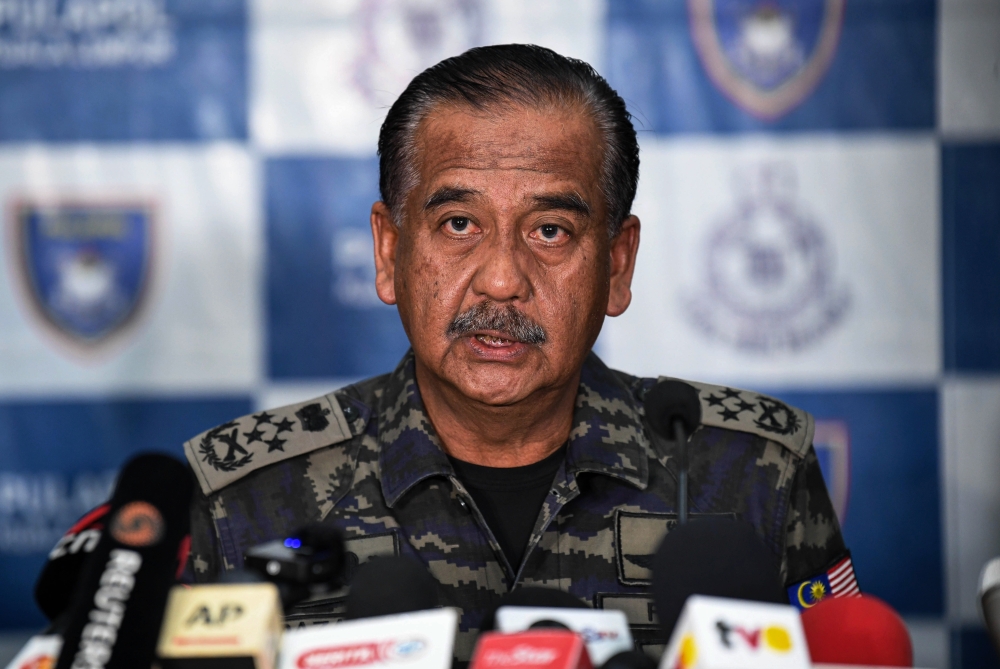

On September 17, Inspector-General of Police Razarudin Husain revealed that the investigation into GISBH had uncovered links to organised crime.

“The modus operandi detected involves moving individuals around to evade detection by authorities. Notably, the victims were not housed in a single location; their placements frequently changed, including those we managed to rescue,” he said.

If by organised crime the IGP was referring to an organised criminal group, then the law applicable is Sosma. It is not the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) — the general law on arrest and investigation.

Even the CPC explicitly states that its provisions do not apply where there is a written law for the time being in force regulating the arrest and investigation, among others, of such offences [Section 3 CPC].

Earlier in the day (Oct 14), a GISBH warden was charged at the Sessions Court at Butterworth, Penang, with sexually molesting a minor at a charity home operated by the firm.

The warden was alleged to have sexually abused the boy, then 13-years-old, by fondling the latter’s penis at Rumah Jagaan Harapan Al Mahabbah, Jalan Bagan Buaya, Bagan Buaya in Nibong Tebal, around two years ago.

If convicted of the charge under Section 14(a) of the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 (Soaca), he could be imprisoned up to 20 years and whipped.

A day earlier on Sunday (Oct 13) three members of GISBH were reportedly charged in the Sessions Court at Kota Tinggi for alleged human trafficking and sexual assault.

The Star reported that two managers of a GISBH-owned resort in Kota Tinggi faced charges of trafficking four individuals for forced labour. The victims involved in the human trafficking case include three women and one man, all aged between 30 and 57 years old.

The trafficking charges fall under Section 12 Atipsom, which carries a punishment of imprisonment for a term not exceeding 15 years, and a fine, on conviction.

The third accused person, a worker at the same resort, was charged under Section 14(a) Soaca with sexually assaulting a 16-year-old boy on two separate occasions.

All three accused persons pleaded not guilty to the charges when they were read out before Sessions Court judge Hayda Faridzal Abu Hasan.

If a group of two or more persons, acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious offences, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a material benefit, power or influence, the group belongs to an organised criminal group.

The offences under Section 12 Atipsom and Section 14(a) Soaca are serious offences. Sosma applies.

However, if it is contended that the arrest and, importantly, further detention of GISBH members are unlawful, a habeas corpus application to the High Court should not be delayed.

Article 5 of the Federal Constitution protects the liberty of a person. Article 5(1) says that no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty save in accordance with law.

Article 5(2) allows a complaint to be made to the High Court or High Court judge that a person is being unlawfully detained whereupon the court shall inquire into the complaint and, unless satisfied that the detention is lawful, shall order the person detained to be produced before the court and release him.

Wrongful deprivation of personal liberties should not be treated lightly.

The remedy of habeas corpus has been said to be “of the highest constitutional importance”, available “to the lowliest subject against the most powerful”.

So, why wait when personal liberties have been wrongfully deprived?

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.