JANUARY 9 — In case you missed the boat last week, here’s the news: this year, two early incarnations of The Walt Disney Company’s iconic mascot Mickey Mouse have finally entered the public domain, 96 years after their debut.

From January 1, 2024 onwards, two classic Mickey Mouse shorts, Steamboat Willie and the silent version of Plane Crazy, will be (mostly) free for the world to use, re-use, parody, upload, download, share, and re-share without having to consult The Walt Disney Company for usage rights.

True to fashion, the Internet immediately delivered: it seems that everyone is joining the party to welcome Mickey’s long-awaited “liberation” from his copyright guardians.

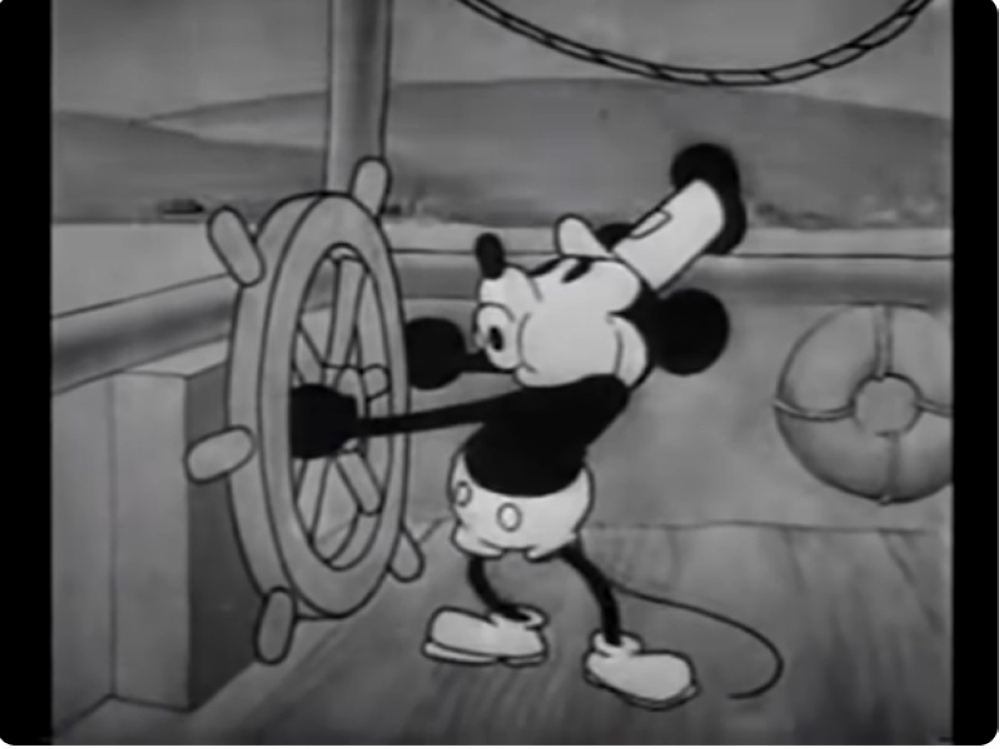

Already on TikTok and YouTube, there are thousands of remixes of Mickey Mouse in his instantly-recognisable getups as the hapless captain in Steamboat Willie and a bumbling pilot in Plane Crazy, from humorous voiceovers to music videos and even spliced edits of him merrily steering the Titanic right into an iceberg.

At least two movie trailers have been released in which Mickey Mouse is reimagined as a serial killer. This spontaneous outburst of public-driven creativity is, after all, a celebration that was almost a century in the planning, a global homecoming of sorts for everyone’s favourite animated rodent.

So how did Disney manage to maintain its copyright hold on Mickey Mouse as long as it did? For answers, let’s travel back in time for a look at historical US copyright legislation.

When Steamboat Willie and Plane Crazy first hit theatres in 1928, they were governed by the Copyright Act of 1909. Under this Act, a creative work could obtain federal copyright for 28 years from the date of publication, with an option for one-time renewal for another 28 years, for a combined total of 56 years. This meant that the copyrights on these cartoons were supposed to expire automatically in 1984.

In 1978, the Copyright Act of 1976 came into effect. This Act (the primary copyright legislation in force in the United States today) revised the subsisting copyright length for works published before January 1, 1978 from 28 years to 47 years. Disney’s rights to Steamboat Wilie and Plane Crazy were thus extended by another 19 years to 2003.

Then came 1998. As the clock ticked on Disney’s ownership of the shorts, Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act. The operative clause was that any copyright still within its renewal term was extended to 95 years from the original copyright date, after which the copyright would lapse in the following calendar year.

This, then, was the key amendment that granted Disney an extra 20-year lifeline on its copyrights in Steamboat Willie and Plane Crazy. On paper, the 1998 Act was officially called the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (after Rep. Sonny Bono of Sonny & Cher fame), but cynical observers were quick to nickname it the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act”.

To be fair though, Disney had not been the only one lobbying for the Act to be passed. Many of the major film studios supported its enactment, and the Act also protected many classic 1920s jazz standards written by the Gershwin brothers.

It just happened that, being such a well-known pop culture icon, Mickey Mouse inadvertently became the scapegoat (or scapemouse, if you will) for the passing of the much-vilified Act.

Come 2024 and that’s all water under the bridge. Now that Steamboat Willie and its companion cartoon Plane Crazy have at long last cruised into the public domain, what does this mean for the artistic geniuses among us?

Do we have free rein to repurpose Mickey Mouse for our own creative ends? Stencil his likeness on our merchandise? Turn him into memes that can be templated and recycled ad infinitum? Well, yes... and no.

You may notice that the version of Mickey in the Plane Crazy and Steamboat Willie shorts is significantly different from his later, more familiar iterations.

Mickey as he appears in the earlier cartoons has a more elastic rubber-hose body, noticeably larger eyes, and doesn’t wear gloves, to name a few of the more obvious dissimilarities.

It is this rendition of Mickey Mouse that is fair game for content creators to use as they please. The more recent versions of the Mickey character, such as that depicted in the 1940 animated feature Fantasia, will remain closely guarded in Disney’s copyright vaults, off-limits to public use for at least a few more years.

We must also remember that Disney still owns trademark rights in the name “Mickey Mouse” and the well-known “Mickey Mouse ears” silhouette, among many others.

While copyrights have a shelf-life, trademarks have no expiry date, as long as they are continuously renewed and actively used bona fide in commerce.

Since it is very unlikely that Disney will ever relinquish its rights over its flagship Mickey Mouse trademarks, would-be entrepreneurs must be careful to ensure that their products would not confuse or mislead consumers into thinking that such goods originate from The Walt Disney Company, when in fact they do not.

One final note: copyright lifespans differ from country to country. Under Malaysia’s Copyright Act 1987, for example, copyright in literary, musical, or artistic works persists throughout the author’s lifetime plus 50 years after their death, compared to 70 years in territories such as the United States, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, and Europe.

There are ongoing efforts by stakeholders, including the Recording Industry Association of Malaysia (RIM), to extend copyright protection to 70 years and harmonise our laws with other jurisdictions, although the latest amendments in 2022 did not address this issue.

We’ll revisit this space if and when Parliament does decide to add a few more years to Malaysia’s copyright life expectancy.

But in the meantime, let’s roll out the welcome mat for a certain somebody who has just anchored safely on shore. Say hello to the public domain, Mickey Mouse. The world has waited 96 years at the pier for you.

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.