JULY 4 — Foreign direct investments (FDI) are an injection of resources from the rest of the world into a country.

It usually brings new technology and forms of organisation, thus promoting growth and economic progress.

Nonetheless, Malaysia was among the Asean countries leading in attracting FDI, illustrating an overall success story over the past decades.

However, Malaysia demonstrated a reversal of this behaviour in the period preceding the pandemic, with a significant decline in these flows, thus agitating the economic and political debate following these adverse outcomes.

This raised the pressure on the government to focus on its responsibility in creating an efficient and viable environment as well as tailored incentives to stimulate FDI.

The recent data released by the Statistics Department showed a new high in FDI reached in 2021, with RM48 billion in monetary terms, reigniting the debate about the government’s merits and demerits in attracting foreign investment and investors.

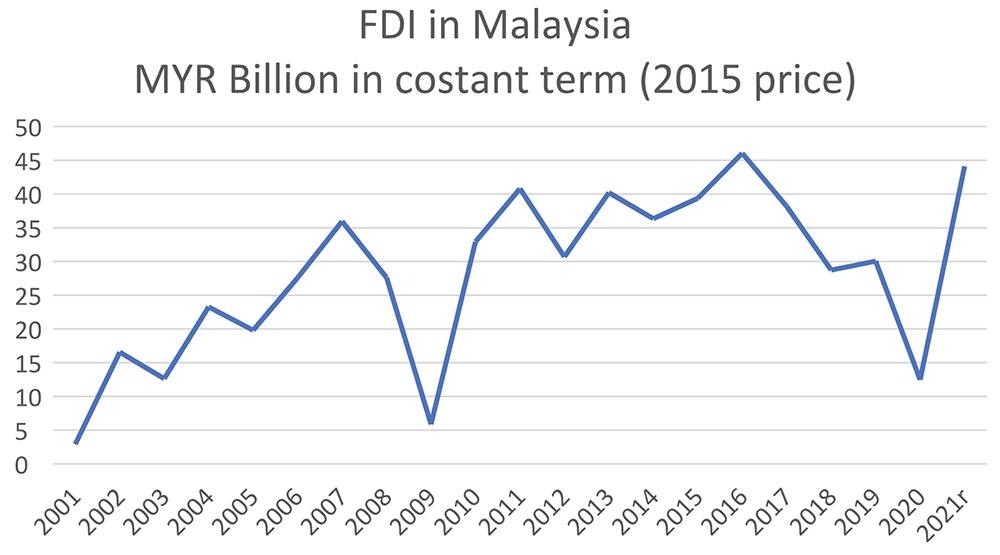

Dynamic of FDI inflows in Malaysia measured in real MYR terms (2015 constant prices)

The graph above shows the FDI measured in real terms (at constant prices), apart from the 2009 international financial crisis that bent the trend of FDI and reduced the economy’s growth.

It clearly shows the two distinct periods of positive FDI trend — with 2001-2007 signifying a more substantial upswing while 2011-2016 seeing a more moderated one.

However, given the fact that Asean FDI was on the rise, 2017-2019 appear with an odd perception. As a result, it has sparked debate and criticism toward the government, given that the sharp decline in FDI was unjustifiable.

The general academic explanation of FDI is based on a series of push and pull factors, but no one-size-fits-all model applies.

Both macro and micro perspectives in extensive studies focus on structural characteristics of the economy, like natural resources, market size, infrastructure, the openness of the economy, labour productivity, human capital, operating costs, and financial determinants like interest rate, exchange rate, and inflation.

The micro aspects added to the explanation are typically qualitative in nature, focusing on proactiveness and effectiveness in dealing with attraction related to the host country’s offers and policies.

Nevertheless, the general perceptions of corruption and political stability also play a critical role in building the investors’ confidence.

In short, the investors are typically clear about the objectives, and the attraction stems primarily from the rent-seeking benefit enabled by the host country.

To understand better the prevalent nature of the FDI determinants in Malaysia, we conducted an econometric analysis, contrasting two different approaches within the eclectic theory of Dunning.

The theory was inspired by the belief that investors were meant to benefit from the host country’s market, resources, efficiency, and strategic assets.

Stressing the emphasis on the importance of institutions, we have also considered these qualitative factors to measure the effectiveness of institutions, political stability, and corruption.

It is an approach that aims to broaden the variables in order to provide a better explanation for the recent changes.

In doing so, we benefited from market experts represented by eminent representatives of the major Chambers of Commerce of foreign countries operating in Malaysia.

The type of analysis conducted distinguishes between variables affecting the long-term dynamics of FDI from those influencing only the short-term fluctuations around the long-term trend.

In conducting the analysis, we focused on the main determinants explaining the majority of the FDI variability in a parsimonious way.

Despite the irregular pattern of FDI observed in the graph, long-term determinants are found to explain more than 94 per cent of the overall dynamics of FDI.

The analysis includes the consideration of two dummy variables which account for the two shocks coming from the international financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic that induced the lockdowns.

The two main variables explaining the FDI and sharing a common trend with FDI in real terms are the real GDP and the rental (measured in percentage terms) coming from Malaysia’s important natural resources.

Intuitively, investments are incentivised by the return they produce, either in terms of the economy’s overall performance or in terms of income — the form of rental — derived from the exploitation of the abundant natural resources that characterise the economy.

Considering the short-term variables explaining the effective dynamics of FDI in fluctuating around the long-term trend, other important variables emerging from the estimates are the openness of the economy and labour productivity, both with a positive contribution to the FDI.

Within this modelling, the surprising result obtained in 2021 is explained by back-to-trend dynamics, countering the divergence from it in 2017-2019, before the pandemic.

In other words, the rebound of the economy in 2021 has set in place the macroeconomic conditions bringing to the positive performance of the FDI.

The econometric results do not simply imply that the institutional and qualitative variables regarding the business environment and the incentives do not play a role in determining the FDI.

All these variables are very important in relative terms: the choice to invest in Malaysia is compared with the one of investing, for example, in Indonesia.

In evaluating the relative conveniences, similar incentives neutralise each other or play only a specific role at the moment they are put in place.

Still, they do not exert a systematic and homogeneous influence on the FDI that can be accounted for in the econometric analysis.

A final consideration is relative to the effects of the structural breaks we observed in 2009 and 2020.

The overall result of FDI modelling confirms and is consistent with other analyses in terms of permanent damages of the shocks to the economy.

This implies that once the shock has passed, there are no “back to normal” dynamics in key variables such as growth potential, productivity, and FDI; instead, we are left with lower levels of these variables, indicating a deterioration of the economic system’s capacity to perform as before.

From this point, so-called “structural reforms” that can put the Malaysian economy on a solid long-term growth path with strong fundamentals are critical.

The downtrend of recent years in private investment is not a good sign, and much more has to be done to exploit and incorporate into the productive structure the potential coming from digitalisation and IR 4.0.

The pandemic diverted attention and resources from these strategic targets; it is time to refocus and re-energise a long-term policy centred on these targets.

The final result of these policies will not only place Malaysia within the high-income countries club but will also push it to become a country with a prominent role as one of the most modern and dynamic countries.

* Paolo Casadio is Professor of Economics and Finance at HELP University; Chee Khoon Ng is pursuing his DBA at HELP University with a thesis on FDI.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.