KUALA LUMPUR, March 14 — My watch asking me if my period has started yet is not what I thought the 21st century would look like. Not that it’s a bad thing as it’s long past due for periods to be considered “just another” health metric, the way heart rates and sleep patterns are.

Yet it was just a week ago when the official supporters club of a certain politician called a recent free menstrual pad drive shameful, asking “Mana maruah kau?” (Where is your honour?)

This stigma associated with menstruation is old and crosses cultures and countries; in Nepal, despite a law banning them, menstruation huts where women are made to sleep apart from others during their periods still exist.

Women’s health in general is under-researched and underfunded. In the UK, less than 2.5 per cent of publicly funded research goes to reproductive health, despite there being one in three women there who will suffer from reproductive or gynaecological issues.

Meanwhile, there are five times more studies about erectile dysfunction which affects 19 per cent of men, compared to studies about PMS that affects nine out of 10 women.

On telling your iPhone about your period

The Apple Women’s Health Study, run by a team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, might seem opportunistic on paper but the reality is that a widespread and publicised study backed by a large corporate name matters.

The study has 10,000 participants spread over ages and races in the US, a fairly large sample size. This is possible due simply to Apple having access to a large user base for data gathering.

Why does collecting all that data matter? Apple’s statement sums it up thusly: “Without substantial scientific data, women’s menstrual symptoms have historically lent themselves to dismissal, or have even been minimised as overreaction or oversensitivity.”

It’s an opt-in process: US users can simply access the Research app and let their period tracking data be used as part of the study.

Apple’s period tracking is opt-in in the way it’s designed. If you have no desire to track your period, or have an app you prefer to use instead, you could choose to turn off notifications and on the Apple Watch, hide Cycle Tracking.

The only significant hole I see is how gendered it is, leaving out those who are intersex or trans.

As to accuracy, I would say as someone who has been tracking my own period over the years, the app is fairly easy to use — on the iPhone it is embedded within the Health app and on the Watch, it is a separate app.

Of course you need to feed it more data to make it more useful; the more periods it tracks, the better it can gauge when your next period is.

Besides just tracking which days you had flow, you can easily add symptoms such as fatigue, appetite and sleep changes as well as factors to consider such as pregnancy, lactation and contraceptive aids.

I found it personally useful as I had a record of a time when my periods were regular as clockwork, and a time where it was incredibly erratic — being able to see that map of my cycles made it easy to describe my symptoms to a doctor.

Something as simple as writing it down goes a long way into not just creating an adequate treatment regime, but to get a doctor to take your discomfort seriously instead of waving it off as “just your period.”

What is there to learn

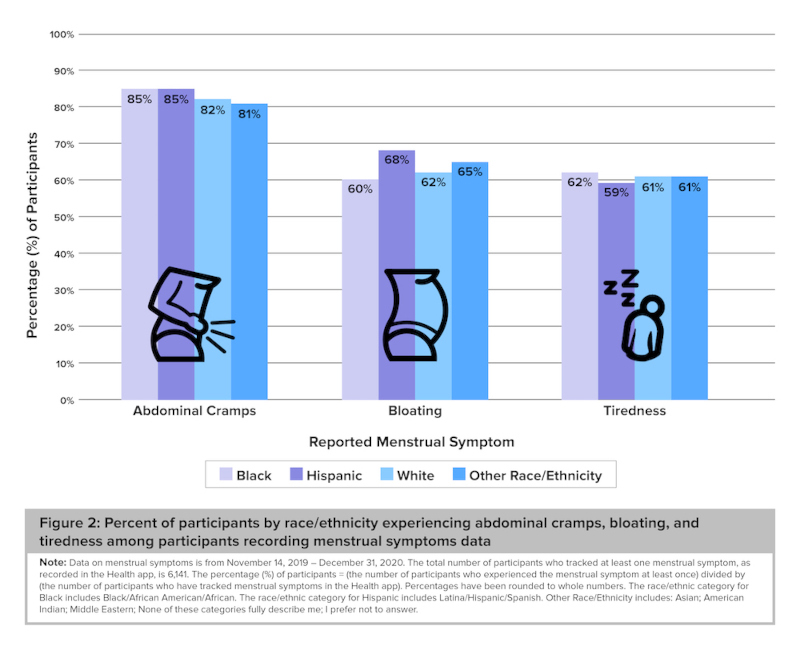

So far the study has provided insight into just how common many reported menstrual symptoms are among women across various different demographics.

Abdominal cramps for instance were reported in over 80 per cent of women in all different ethnicity categories, with abdominal cramps being the most reported symptom in the study overall.

Having that data made easily and publicly accessible is important not just for other researchers but for women themselves; to know they’re not alone, that many women share the same issues they do.

In a statement, Dr Michelle Williams, Dean of the Faculty at the Harvard T.H. Chan School said, “By building a robust generalisable knowledge base, the Apple Women’s Health Study is helping us understand factors that make menstruation difficult and isolating for some people, in addition to elevating awareness of a monthly experience shared by women around the world.”

Of course, the argument could be — the average woman knows this, that discomfort, the pain, the general inconvenience of menstruation in general. Why haven’t we just been listening to them?

Large-scale projects such as these might be a start to more widespread, well-funded studies about women’s health beyond just menstruation. Recently there were reports about women in general showing more side-effects to Covid-19 vaccines, despite them participating in previous trials.

The consensus was that these trials did not distinguish and examine side effects by sex, and did not try to ascertain whether lower dosages could be an option for women so they would have fewer side effects.

With more data, perhaps we can look forward to a future where women would have access to better health care options than what they do today.

In the meantime, I guess I’ll keep talking to my watch about my period.