- More Singaporeans are speaking English at home, as mother tongues fade into the background

- While some parents and students view their mothers tongues simply as an academic requirement, others stress its cultural significance

- Among the attempts to make mother tongue learning more engaging is a new primary school syllabus being progressively rolled out from this year

- Though some young Singaporeans feel indifferent about their mother tongues, experts caution against the dilution of Singapore’s linguistic diversity

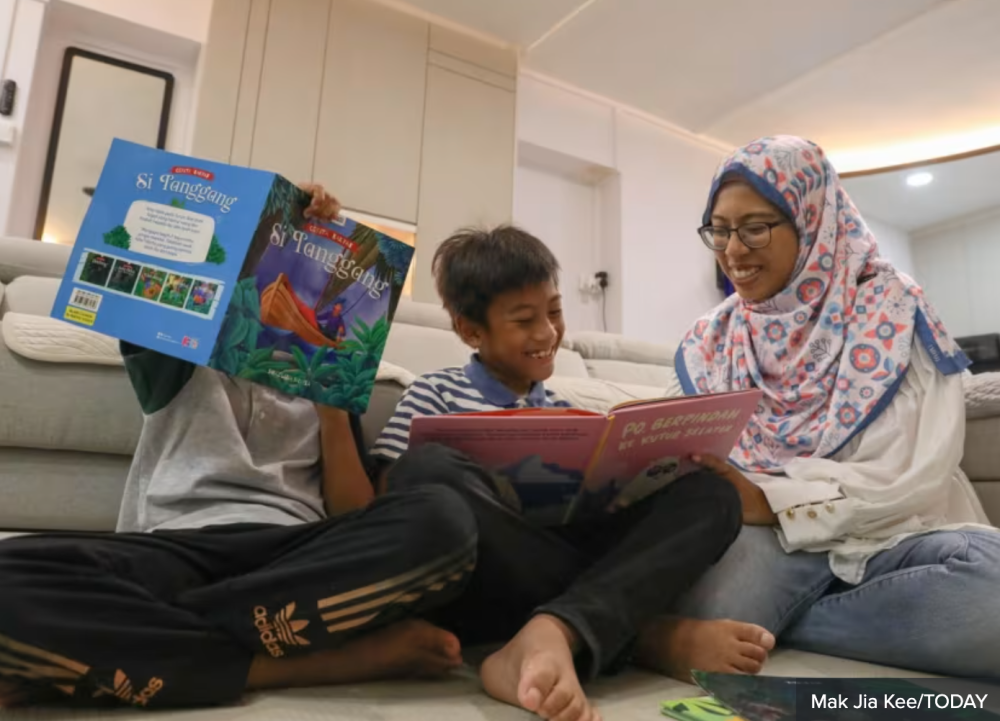

SINGAPORE — Mother of three Nur Asyikin Naser uses the limited time she has while driving her children to school to cultivate their love for their mother tongue by playing Malay language audiobooks during the commute.

At home, the 35-year-old secondary school Malay language teacher would introduce Malay stories and movies to the kids, aged four to nine. She also encourages her two older children in primary school to keep a bilingual journal, and to write short cards in Malay for their grandparents.

Ms Asyikin recently connected with nearly 100 mothers on a WhatsApp chat group providing Malay language penpals for their children.

“On Facebook, this mummy was lamenting that her daughter’s writing in Malay was very atrocious, so she suggested forming a small group (for their children) to exchange letters. It became quite a big thing, because there was a lot of response,” Ms Asyikin said.

While she has succeeded in fostering a love for their mother tongue in her own children, it remains a work in progress for her other “children” — the students in her Malay language classes.

Ms Asyikin said many of her students struggle to form sentences in Malay during lessons due to a lack of practice outside of class.

As for 35-year-old digital marketer Roystonn Loh, who is a father of three children, aged two to seven, he has seen his children’s eyes “glazing over” when family members try to speak to them in Mandarin. After all, English is the main language at home for the Lohs.

An attempt to maintain a “dual-speaking” home environment, where Mr Loh spoke only Mandarin and his wife, English, lasted for just two weeks before both parents reverted to English.

“At work, you speak in English, so it’s hard to switch and maintain this duality. And your children are more or less the reflection of you,” he said.

With English having been the main language of instruction in schools here for decades, Mr Roystonn Loh’s children are among the younger generations of Singaporeans who feel less at home with their mother tongues and are more comfortable using English.

With Singapore celebrating National Day on Friday (Aug 9), TODAY takes a closer look at the evolution of this fundamental marker of identity and culture.

Losing language, so what?

A 2020 study by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) on race, religion and language found that 61 per cent of parents between 26 and 35 years old used English the most frequently with their children.

In contrast, only 45 per cent of parents aged between 56 and 65 used English most frequently with their children.

The widespread use of English at home was also accompanied by more Singaporean Chinese and Indian respondents increasingly identifying with English as opposed to their mother tongues or heritage languages.

Malay respondents were more likely to indicate that they identified most with their mother tongue, indicating “strong links” between Malay language and identity, the IPS study said.

This shift in using English as the “home language” can be attributed to a pragmatic attitude among parents and grandparents in Singapore, said Dr Goh Hock Huan, an education research scientist at the Centre for Research in Pedagogy and Practice at the National Institute of Education (NIE).

Some may also lack confidence in using their mother tongue, while inter-racial and transnational families are more likely to use English at home, he added.

The mother tongue policy in schools, which usually assign children a mother tongue other than English on the basis of their ethnicity, also influences their attitude towards learning the language, said Associate Professor Susan Xu Yun from the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS)

The three official mother tongue languages are Chinese, Malay and Tamil.

“To these children, mother tongues that are not spoken at home by their parents or grandparents are merely one of the many subjects in their 12-year formal education,” said Assoc Prof Xu, head of the Translation and Interpretation Programme.

“Without much motivation, practice and exposure, their mother tongue proficiency developed through school syllabuses is understandably limited.”

Undergraduate student Liow Wan Yu, 21, is fluent in Mandarin but has little opportunity to speak it with her peers, who predominantly come from English-language speaking homes.

“Having to speak it (Mandarin) at home helps a lot. I think once Chinese is no longer an examinable subject, that’s when most of my friends lost touch with the language,” said Ms Liow.

The widespread use of English at home was also accompanied by more Singaporean Chinese and Indian respondents increasingly identifying with English as opposed to their mother tongues or heritage languages.

For Mr Loh and his wife, Mandarin proficiency was not a concern until he realised that there was a gap between his daughter’s current mother tongue ability and the primary school subject requirements.

His concern over his children’s Mandarin proficiency is “purely academic”, as he is comfortable sharing Chinese culture and traditions with his children in English.

But others feel there is more at stake: For them, speaking their mother tongue at home connects their family to their culture and heritage.

Ms Asyikin, the Malay language teacher, said many of her teenage students default to using the informal pronoun “aku” to refer to themselves instead of “saya”, which is more respectful when addressing teachers and elders.

“To me, it’s not just about language, it’s also about identity. When you speak the mother tongue, there are certain values, such as respect and politeness, that you learn, as compared to English,” she added.

Though some maintain that culture and language are separable, Dr Goh from NIE said that language transmits “cultural resemblances” through its actual use and script, which another language “cannot fully reflect and transmit”.

While cultural practices and traditions may not be “language-bound”, each language opens up more worldviews, said Associate Professor of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies Tan Ying Ying from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

She pointed to Chinese ideas of kinship, reflected in the meticulously categorised terms for familial relationships such as 舅舅 (jiu jiu) for maternal uncle, which provides a “glimpse” into what it might mean to be part of a Chinese family system.

There are also practical benefits from mother tongue fluency, such as maintaining connections with older generations.

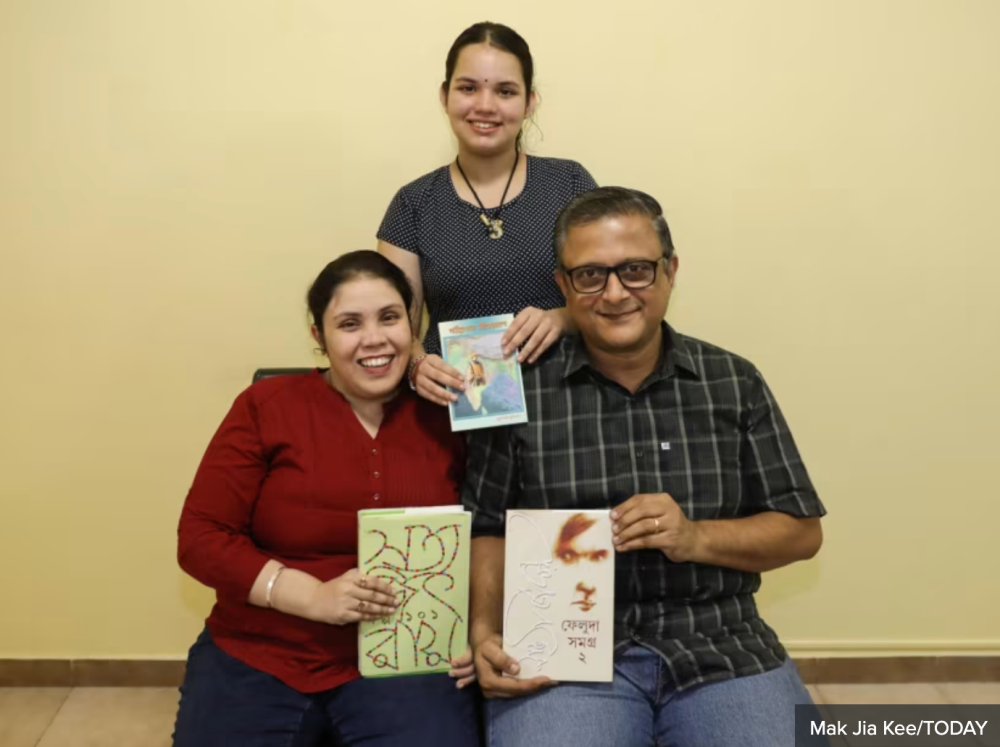

For 14-year-old Shreya Archita, having Bengali as her mother tongue language means waking up early on Saturdays for lessons, since her school offers only Tamil.

Yet, she looks forward to these lessons and has received awards, such as being the top-scorer in Bengali in Secondary One.

More than good grades, her nightly phone chats in Bengali with her grandfather, who stays in Kolkata, India, also motivates her to keep learning the language.

“Speaking Bengali makes me feel connected with my family and more aware of my roots. You need to learn English because it’s universally important, but with Bengali, it’s special. I feel proud of it,” said Shreya.

Home’s where it begins

With the bilingual scale having tilted heavily towards English in recent times, authorities are working to balance it by making mother tongue learning more engaging and accessible.

Last year, Minister for Education Chan Chun Sing announced a refreshed primary school mother tongue curriculum incorporating games and technology during lessons.

In response to TODAY’s queries, the Ministry of Education (MOE) said schools are progressively implementing the new curriculum, and a new series of printed and online readers have been designed to nurture a love for mother tongue language reading.

The ministry emphasised the important role that parents — as the “first teachers” in a child’s life — play in shaping their children’s attitudes and mindset towards language learning.

“In the early years when children are developing their language skills, it is important for parents to show interest in their child’s mother tongue language and model the willingness to learn with their child, even if they may not be proficient in the language,” said MOE.

Parents and experts also largely agree.

Ms Archita Biswas, a 41-year-old quality specialist, cultivated her daughter Shreya’s interest in Bengali through the practice of sharing fairy tales at mealtimes.

Besides getting her daughter hooked on classic Bengali literature, Ms Archita would come up with her own stories to immerse Sherya in the linguistic world of her mother tongue.

“More than talking, it was using Bengali expressions, like if a tiger is saying something, I won’t say that the tiger is ‘growling’ (in English). Instead, I will use the Bengali word হালুম (ha-l-u-u-m),” she said.

Her husband, Mr Vedha Giri, speaks Tamil, so the 49-year-old banker uses Google Translate and his knowledge of other Indian languages to help Shreya with her homework.

Stories were also a means for Ms Ksther Lim, 46, to introduce both language and culture to her son, now 15, as she read him Chinese tales explaining the Mid-Autumn Festival and Chinese New Year celebrations.

Encouraging the teenager to be an “effective” Mandarin speaker, rather than insisting on him being perfectly fluent, helped him understand the importance of staying connected to Mandarin, she said.

The human resource professional said she emphasised to him the practical benefits of speaking his mother tongue, such as avoiding awkwardness at family gatherings with their Mandarin-speaking relatives, and the future need to converse with Chinese-speaking colleagues.

The importance of a parent’s role in the learning of one’s mother tongue cannot be stressed enough, experts said.

Dr Sun Baoqi, an education research scientist from NIE’s centre for research in child development, said one study found that using mother tongue at home and having parents help with mother tongue homework had positive direct effects on students’ motivations to learn.

Mother tongue language tuition, on the other hand, did not appear to lead to any predictions of student motivation or learning behaviours, according to the NIE study.

Parent-teacher collaborations have also proven to be a useful tool.

Ms Uma Devi R Jayagumar, the lead Tamil teacher at preschool My First Skool, said students have responded well to efforts to assignments that encourage out-of-classroom interactions with parents.

She regularly prompts children to practise Tamil at home through exercises such as a journaling assignment where students interview their parents on their occupations.

Another exercise that her students love involves sharing new Tamil riddles during class, which has encouraged the children to research new riddles with their parents.

“It takes two hands to clap, because I can have one hour of lessons and then it’s not reinforced at home. Consistency and exposure are needed,” said Ms Uma.

Language and Singaporean identity

If home is indeed the most important environment for fostering Singaporeans’ connection to their mother tongues, will the trend towards monolingual, English-speaking households impact the identity of a nation that just celebrated its 59th birthday?

Young people are likely to say no.

Ms Ying Xuan Ling, a 22-year-old undergraduate student, said being fluent in Mandarin is “not one of the top qualities” she associates with being Singaporean.

Now an international student studying fashion communication in London, her cohort comprises mostly European and American students, and she only speaks Mandarin with other Chinese friends.

“I don’t think (my concept of cultural roots) has changed much being in London, and the idea of being able to speak Mandarin is viewed as an ethnically Chinese quality, rather than Singaporean,” said Ms Ying.

Others agreed, saying that English is more inclusive than their ethnically-designated mother tongues.

Among them is 15-year-old student Aldrin Ardiansyah Fakhrul-Arifin, who said speaking Malay does not make him more, or less, Singaporean.

Instead, he finds cultural celebrations with family during Hari Raya, and with friends during Chinese New Year, more significant in shaping his identity.

For multiracial families like that of Ms Marsya Ruzana Aw’s, a diverse linguistic background means they have to speak mostly English at home, as it is a “unifying language”.

The 27-year-old grew up speaking Mandarin with her grandparents on her Chinese father’s side and spoke Malay with her mother’s relatives. But she finds it “less critical” that her children actively use both mother tongues.

“The main challenge is persuading my children of the benefits of learning additional languages. Even though their grandparents speak Chinese, integrating the language into their daily lives can be tough,” said Ms Marsya, who is married to a Malay husband and has two children aged three and four.

She plans for her children to learn Mandarin as their mother tongue to “give them more opportunities” when they enter school. She will teach them Malay at home or encourage them to pursue it as a third language.

Dr Tan from NTU noted that it is not surprising that today’s youth are more indifferent to any perceived cultural loss from reduced fluency in their mother tongues, or that they have a stronger connection to English.

Monolingual speakers of English may not feel that they have lost anything because English is highly valued in Singapore, and people may be judged more for poor English as compared with other languages, she added.

“I don’t blame kids these days for saying, ‘I’m perfectly okay with English because I’ve got friends from different ethnic backgrounds, and we all speak English together, because there’s also a sense of building national identity (in that),” said Dr Tan.

At the same time, she cautioned, such a mindset is leading Singapore down the “monolingual road” and its linguistic diversity will eventually be lost.

“If we believe in the idea that languages are repositories of culture, then every language loss is a culture loss,” said Dr Tan.

“If you have three different languages, you actually get glimpses into three different worlds. So if we are monolingual, then we literally have a monolingual worldview.”

Dr Goh from NIE said that having fewer effective bilinguals may result in a lack of local talents in sectors that require mother tongue expertise, such as education, journalism and entertainment.

“In street interview footage using mother tongue, it is quite common to see local interviewees speaking in literal translations of their mother tongue from English,” said Dr Goh.

“As the public becomes accustomed to such expressions, it could potentially impact communication in mother tongue languages and exacerbate imbalanced bilingual development.”

Ultimately, linguistic and cultural diversity is “at the core” of the Singaporean identity, said Dr Xu from SUSS. A monolingual society is likely to be homogenous, potentially perpetuating inequalities such as favouring English-speaking majorities over mother tongue-speaking minorities.

The mother tongue, which as an academic concept is frequently associated with one’s first language, “holds the key” to one’s ethnic identity, said Dr Goh.

“However, this has no conflict with the national identity, as Singapore is a multiracial and multicultural immigrant society. In the past, being able to speak more than one language was a form of local identity and a definite showcase of the kampung spirit.”

Some examples of this kampung spirit would be in saying greetings in the mother tongue of different races and showing respect and acquaintance by speaking some mother tongue languages during different festival occasions of different ethnic communities, he added.

To be fair, there are youths who are keeping this practice alive. Ms Liow the undergraduate, for one, is learning Malay so she can connect better with her Malay friends.

“I started with Malay because it's also the national language and most similar to English, through Duolingo and some Youtube videos. Then when I told my Malay friends, they were quite excited and tried to help me learn the language," said Ms Liow.

“That sparked further conversations (with a friend) about her religion, and to some extent she trusted me enough to share about her feelings about the Muslim community in Singapore.

“Maybe she would have told me nonetheless, but I think it helps people feel more comfortable with you, and feel like you are actually trying to get to know them.” — TODAY