SINGAPORE, Oct 17 — Plumber Tan Zhong He knows he is good at his job. He also knows that his services are valuable — why else would people call him to fix their leaks and unclog their toilets?

So it frustrates the 26-year-old when his customers try to bargain on his fees after he has successfully solved their water woes.

“If people ask for quality service they should be willing to pay more for it. We’re also earning a living, not doing charity, so good and cheap is not an option,” he said.

By and large, it seems that most Singaporean youths agree with Tan that vocational workers like him deserve fair wages.

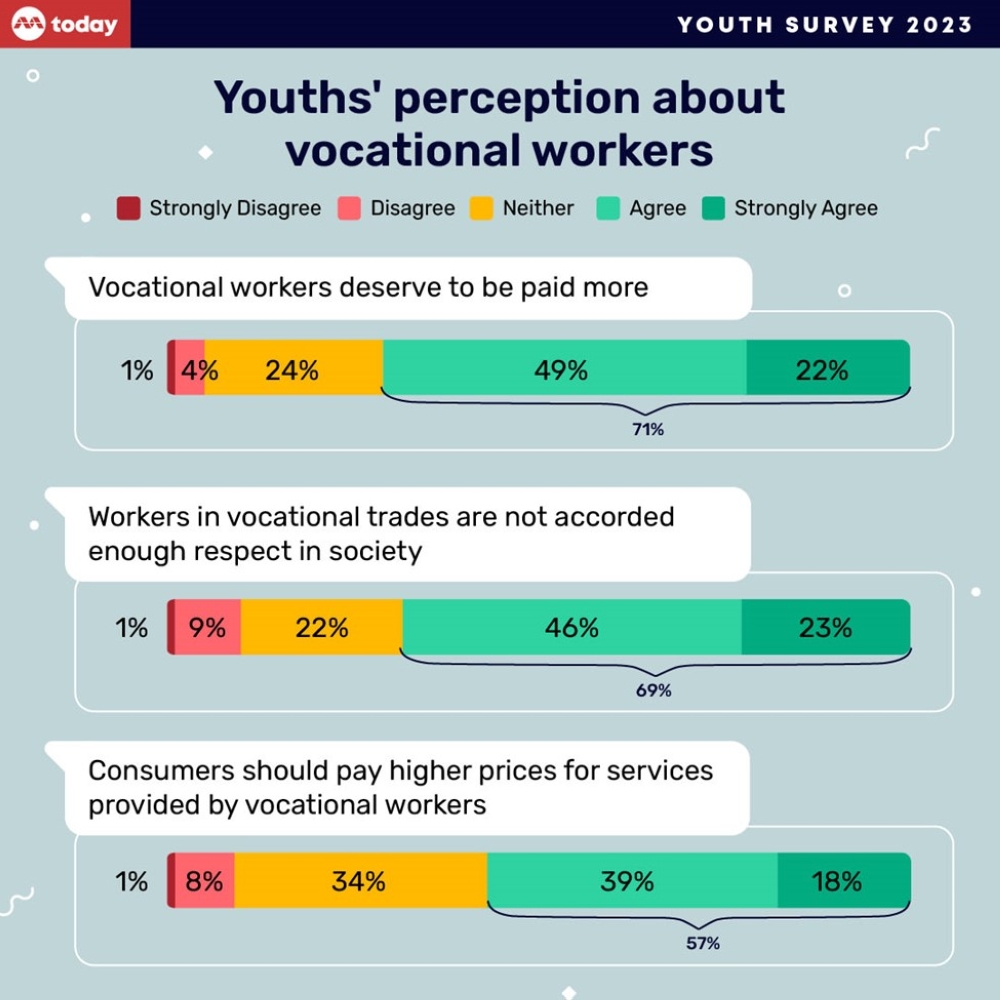

According to findings from TODAY’s Youth Survey 2023 — an annual survey that seeks to give a voice to Singapore’s millennials and Gen Zers on societal issues and everyday topics close to their hearts — 71 per cent of the respondents said blue collar workers deserve to be paid better than they are now.

The survey, which was conducted in August, polled 1,000 respondents aged 18 to 35.

This is the third edition of the survey and it looked at youths’ views on housing, the importance of a university degree, career development, the gap between blue collar and white collar wages, and civic participation.

Wage gap between white and blue collar workers ‘significant’

Almost eight in 10, or 78 per cent, of youths polled believe there is a significant wage gap between blue collar and white collar workers, and that society has the responsibility to address that gap, though fewer — 57 per cent — agreed that consumers should be the ones to bear the cost of narrowing this gap.

The issue of wage disparity between these types of workers is one that has caught the attention of the authorities, too.

Last month, Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong reiterated the growing divergence between the starting salaries of graduates from the Institutes of Technical Education (ITE), polytechnics and autonomous universities over the past decade.

He noted that this “college wage premium” exists in many parts of the world, but Singapore has a higher degree of so-called “occupational wage dispersion” than other advanced economies — a big gap in wages between those who engage in more knowledge-based or “head” work and those who engage in more hands-on and “heart” work, like technicians and service workers.

Statistics from the Ministry of Manpower show that in 2022, the median wage of those in hands-on jobs such as crafts, machine operators and assemblers was half that of the national median wage.

That year, the real median gross monthly salary for an ITE graduate was S$2,000, while that for graduates from the country’s autonomous universities stood at S$4,130, according to graduate employment surveys conducted by the institutes of higher learning.

“We must do all we can to reduce these wage gaps, encourage more diverse pathways, and instil dignity and respect for every job, every vocation, and every skill,” said Mr Wong.

Blue collar trades are essential work

Indeed, results from TODAY’s youth survey found that almost seven in 10, or 69 per cent, of youths believed workers in vocational trades are not accorded enough respect in society.

John Tay, a white collar professional who works as partnerships lead at Singapore-based venture capital firm Tin Men Capital, is among them. The 33-year-old noted that the Covid-19 pandemic had thrust blue collar workers and the importance of their work into the spotlight.

“Right at the frontlines, alongside the healthcare workers, were the workers powering our essential services. We do have a responsibility to ensure that they get paid fair value for their work and the important roles that they play,” Mr Tay said.

Anna Trinh, a training lead for home cleaning service Helpling, agreed, saying that blue collar workers should be accorded the same respect and recognition as other workers.

“After a long, demanding day of contributing to society, returning home to a clean and orderly environment is a well-deserved privilege. The individuals responsible for creating and maintaining that environment deserve appreciation and recognition as well.”

Echoing these sentiments, 30-year-old nurse Staffan Stewart recalled how some members of the public felt “terrified” upon seeing nurses on public transport during the pandemic and avoided them or even harassed them.

“It’s ironic how in nursing, we are dealing with life and death situations and are told that we are the frontliners, angels in white, and all the terms used to remind us that we are handling patients’ lives. Yet, despite all these, the salary that we get doesn’t reflect the importance of our skills.”

But there are those who disagree, and think that it is fair for white collar professionals to be paid much more.

Christopher Tan, 25, who delivers parcels for Shopee and also works as a crew on a yacht, believes that the higher pay for white collar workers is justified, because the job scope demands more certifications and more skilled labour.

“Certain desk jobs that require more skilled workers will pay more, because maybe it’s easier to find blue collar workers as compared to these specific niche jobs,” said Tan.

This was echoed by Dr Alywn Lim, Associate Professor of Sociology at Singapore Management University, who said that differences in wages are usually based on market forces.

“Occupations where skills and credentials are essential and in which human capital takes longer to nurture, for example, professional work where training may take many years, tend to have higher remuneration because those positions are more difficult to replace.”

He added that perceptions of inequality may arise not purely because of the gap in wages across industries, but because the salaries in some industries have been lagging behind inflation.

“The grievance that people may have is that wages are not keeping pace with the cost of living, which has risen dramatically recently and for key items like housing. This has obviously impacted lower income workers more substantially and thus the calls for more attention to blue collar wages.”

Dr Lim cautions that the solution may not be as easy as just raising wages, as an increase in wages without a corresponding increase in skills or productivity would mean more expensive products and services, which would also affect blue collar workers paying for these services.

Artificially raising wages can also lead to perceptions of unfairness, said Dr Lim, since wages are meant to correspond to how much value society assigns to different occupations in a meritocratic society.

“Wage equity is an interesting problem because, on the one hand, high wage inequality in a society may rigidify into hard class distinctions. This has obvious implications for social cohesion. On the other hand, meritocracy demands that there are different wage remunerations for different levels of expertise, replaceability and work,” he said.

“An artificial levelling of wages, that disregards training, education, skills and value, may also lead to a perception of unfairness.”

Joint effort needed to address the gap

Marcus Pang, a 27-year-old project coordinator at a local waterproofing company, believes consumers have to accept that if they feel blue collar workers deserve more pay, then they have to contribute, too.

But he added that the Government can also help to “elevate” this idea so it becomes a social norm, as current perceptions of vocational industries are deeply ingrained in society.

“You’re not paying them for that 20 minutes or one hour of work. You’re paying them for the years of experience that they have gathered over the years,” he said.

Similarly, Tay, who works at the venture capital firm, believes that consumers have to “accept a new norm” if they believe the blue collar workers in society deserve better pay, though businesses should also be more open to sharing the pot when possible.

“Companies and corporations have a responsibility of being nimble in shifting profits towards workers who have worked to achieve the growth,” he said.

Others noted that for consumers to be willing to pay more for services, the scope of blue collar jobs must be “enriched” and professionalised.

This is the case in Germany, where workers in blue collar industries are respected as highly skilled craftsmen, said Associate Professor Tan Ern Ser, a sociologist from the National University of Singapore.

“The difference lies in their possessing a combination of complex skills, involving both cognitive ability and master craft skills,” he said.

“To bring about fundamental change, we would need to restructure the education system, to rethink education and training curricula, and to redesign jobs to incorporate head, heart and hand ability and skills.” — TODAY