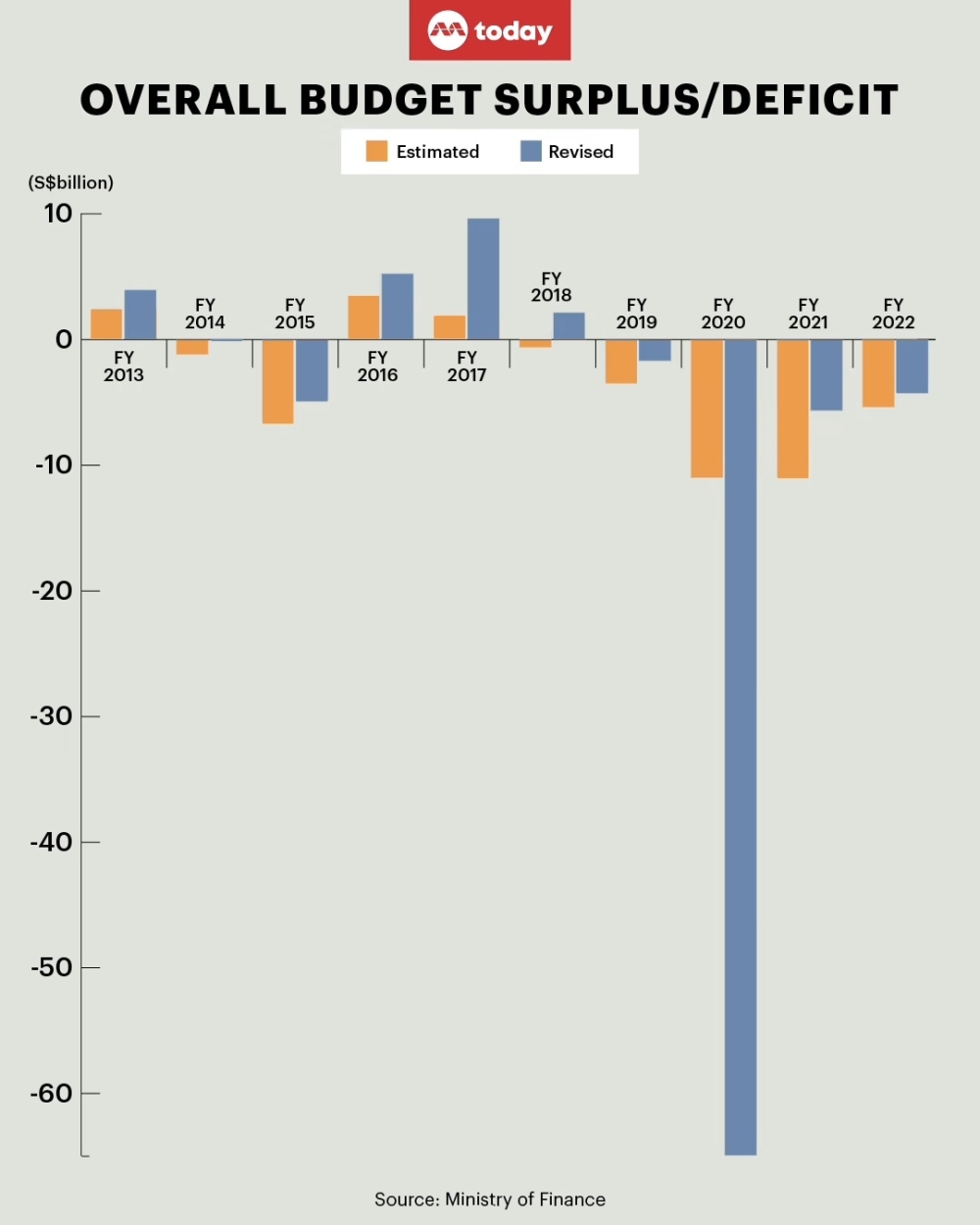

SINGAPORE, Feb 17 — Apart from the headline-grabbing Budget 2023 measures, it has not gone unnoticed that the Government’s financial numbers have tallied with a general trend over the past decade: Its budget deficits are usually not as large as predicted, while surpluses are usually bigger than expected.

In the analysis of revenue and expenditure released in tandem with the 2023 Budget statement, the overall budget deficit in the financial year (FY) 2022 was S$4.22 billion (about RM14 billion), lower than the S$5.34 billion forecast when Budget 2022 was announced in February that year.

Such overestimation of deficits or underestimation of surpluses has been the norm over the past 10 years, with just one exception: In FY2020, when Covid-19 first hit Singapore.

In that year, the estimated deficit was S$10.95 billion while the revised deficit turned out to be a whopping S$64.9 billion. That initial estimate was made when the Budget was delivered in February 2020, before the full economic impact of the pandemic was clear.

Other than that year, every other year has seen a prudent estimation of the budget surplus/deficit, with FY2018 even seeing an estimated deficit of S$600 million turn into a revised surplus of S$2.12 billion.

This “prudent approach” is also seen in the way the Government uses its national reserves, as Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Lawrence Wong put it on Tuesday (Feb 14) in his Budget 2023 speech.

The Government will draw on the reserves “judiciously, only when there are compelling reasons to do so”, Mr Wong said.

For instance, in FY2022, the Government drew on past reserves to fund Singapore’s emergency Covid-19 public health and related expenditure.

While President Halimah Yacob had earlier concurred with a drawdown of up to S$6 billion specifically for this purpose, the stabilisation of the public health situation meant that a lower amount of up to S$3.1 billion was expected to be drawn from the past reserves.

At the same time, the total expected drawdown on Past Reserves from FY2020 to FY2022 was S$40 billion, which was lower than the initial draw of S$52 billion for which the Government had sought and obtained the President’s agreement.

This has raised questions about whether the Government is too conservative and what is the trade-off for citizens?

For instance, can the Government continue justifying tax increases when the Budget shows a higher-than-expected surplus or lower-than-expected deficit for most years?

TODAY put these questions to economists and policy experts.

Can the government be considered conservative in its budget approach?

Experts were divided on whether the Government can be considered “fiscally conservative” in the technical sense.

Associate Professor Eugene Tan, a law lecturer at the Singapore Management University, said that successive governments under all three of the nation’s prime ministers have been and are prudent in managing the national budgets.

This is not necessarily a bad thing.

“This means that the Government has been prudent and disciplined in the use of fiscal resources, manifested in balanced budgets and surpluses in most years,” he said.

He added that such prudence is a “governance norm” as it is backed by constitutional requirements of balanced budgets and a demanding process before drawdowns on past reserves can be made.

Mr Christopher Gee, head of the governance and economy department at the Institute of Policy Studies, said that the term “fiscal prudence” would be a better way to characterise the Government’s spending patterns, rather than “fiscal conservatism”.

He said that fiscal conservatism tends to be associated with:

1. Balanced budgets

2. Tax cuts

3. Reduced government spending

4. Minimal or low government borrowing

Mr Gee said it can be argued that Singapore takes an approach of achieving balanced budgets and minimal or low government borrowing.

However, the other criteria of tax cuts and reduced government spending do not apply so much here.

The Ministry of Finance (MOF) last week released a paper saying that the Government may need to raise more revenue in the years ahead to keep up with higher spending on healthcare and infrastructure, for example.

“On keeping a balanced Budget, Singapore governments are held to this by the constitutional requirement for Budgets to be balanced within the term of each government, and in terms of minimal or low government borrowing, it is really the only consistent indicator that the government is fiscally conservative,” Mr Gee said.

What is the trade-off of fiscal prudence?

The experts said that fiscal prudence may be perceived by the public as overly conservative during times of stability, but it is during times of crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic that the dividends of such an approach is appreciated.

Sumit Agarwal, a professor at NUS Business School, said that although the Government had either overestimated deficits or underestimated surpluses in the Budget for nine of the last 10 years, the one year in 2020 during Covid-19 where it did not do so “dwarfed” all the other years of prudence.

That year, the estimated deficit was off the mark by more than S$50 billion. In comparison, the total funds from the overestimated deficits and underestimated surpluses of the other nine years totalled just under S$25 billion.

Sumit said that citizens should not prejudge the prudence during times of stability because such funds could be needed in a future crisis.

“People should not be thinking that the Government is trying to extract higher taxes just because they show more deficits but end up not spending it,” he said.

“We don’t know what kind of shocks the Government will experience in the future, and so this will all be balanced out in the big picture.”

Why is fiscal prudence important for Singapore?

OCBC bank’s chief economist Selena Ling said that when it comes to fiscal prudence, it is important to keep in mind Singapore’s context, given that it is a small, open economy that is “largely dependent on the global economic environment and could turn on a dime”.

“Given the heightened economic volatility and uncertainties, (fiscal prudence) is not necessary a bad approach as it has helped the country build up significant reserves since independence,” she added.

“From an inter-generational perspective, this is also good because you’re not spending today at the expense of future generations.”

Mr Gee said that the fiscal stance that Singapore takes is “unlike most governments elsewhere in the world”, but this has resulted in the country being able to accumulate a substantial public surplus in its reserves.

“The happy result (is) that the net investment returns contribution (NIRC) now forms the Government’s single largest source of revenues, larger than any another tax revenue source since 2016,” he added.

The NIRC framework allows the Government to spend up to 50 per cent of the net investment returns on net assets invested by Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC, the Monetary Authority of Singapore and state investment firm Temasek Holdings and up to 50 per cent of the net investment income derived from past reserves from the remaining assets.

What happens to the ‘spare’ S$10 billion in the contingencies fund?

Mr Wong also spoke on Tuesday in Parliament about the Government’s plans for the Contingencies Fund, which is a reserve of money set aside to cover urgent, unforeseen expenditures.

In May 2020, the Government raised the Contingencies Fund’s balance from S$3 billion to S$16 billion to ensure that it could respond quickly to urgent and unforeseen cashflow needs arising from the fast-evolving pandemic, Mr Wong said.

He also said that with the return to normalcy, the balance of the Contingencies Fund will be reduced from S$16 billion to S$6 billion.

There is no legal mechanism to make a reduction to the fund, so the Government will amend the Constitution for this purpose, he added.

Responding to queries from TODAY, MOF said on Thursday that the S$10 billion taken from the Contingencies Fund will go into the Consolidated Fund.

“The Consolidated Fund is analogous to a bank account held by the Government, which contains the balances of funds from revenue collection and is used to pay for government expenditures.”

Mr Wong said that the Contingencies Fund is a separate fund that the Government taps to meet “urgent and unforeseeable needs with concurrence of the President” and that any advance from the Contingencies Fund must be repaid.

Transferring the balance in the Contingencies Fund to the Consolidated Fund does not change the amount of resources that the Government can spend, MOF said.

“To spend, the Government has to move a Supply Bill through Parliament.”

The reserves are also not affected by this change.

“This is because the total amount of assets owned by the Government is the same whether the amount sits in the Contingencies Fund or the Consolidated Fund,” MOF added. — TODAY