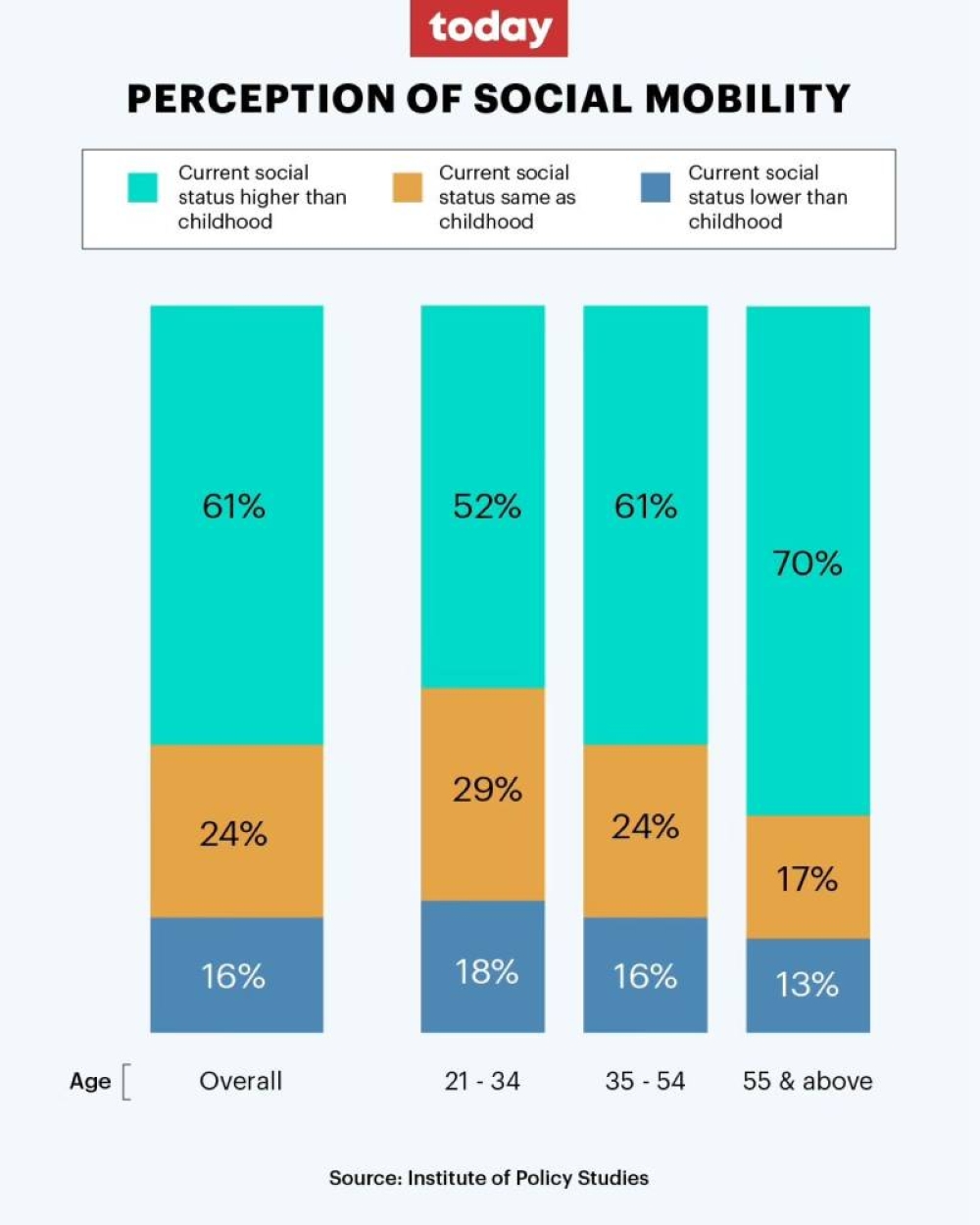

SINGAPORE, Jan 16 — Younger people between the ages 21 and 34 are less likely to have seen their social status rise, compared to those who are older, a study by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) released on Monday (Jan 16) has shown.

The study, titled “Survey on Singapore workforce’s preparedness for the future of work, their work aspirations and perceptions of social mobility”, showed that respondents aged 55 and above are more likely to have seen a rise in their social status.

Seven in 10 among this group do so, compared to 61 per cent of those aged between 35 and 54, and 52 per cent of those aged 21 to 34.

The study, which surveyed 1,010 working adult Singaporeans aged between 21 and 84 in October last year, took stock of social mobility in an effort to understand “how Singaporeans are likely to fare in jobs of tomorrow and where vulnerabilities may lie”, a release on the study said.

Social mobility and inequality in Singapore have been hot-button issues in recent years.

In 2018, then-Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam urged Singaporeans to keep the “escalator” of social mobility moving. He warned that once it stops, those caught in the middle will be steeped in “pervasive anxiety” of not only trailing those advancing further, but also looking over their shoulder at those who are catching up.

A report by the World Economic Forum in 2020 on social mobility found that despite outperforming its South-east Asian neighbours, Singapore ranks 20th out of 82 countries surveyed.

How IPS tracked social mobility

The researchers used what is known as MacArthur’s Social Status Scale or MacArthur’s Ladder, where respondents were presented with an image of a ladder with 10 rungs and asked to imagine that it represents their society.

“The top rung (10) represents people with the most wealth, education and respected jobs, while the bottom rung (1) represents the most impoverished and least educated with the least respected or no jobs,” said IPS. Respondents were then asked to rank themselves on this ladder.

First, they were asked to recall their childhood circumstances at age 18 or earlier and provide a ranking, and then were asked to consider their present circumstance and provide a current ranking.

“An increase in ‘ladder scores’ from childhood to present circumstances suggests upward social mobility, and vice versa for a decrease in ‘ladder scores’,” said IPS.

The study found that overall, six in 10 respondents report higher scores now, meaning they experienced upward social mobility compared to childhood. This compared to 24 per cent who report no change in scores, and 16 per cent who report a decrease in scores.

The results were also broken down by age, and the breakdown showed that younger respondents are less likely to have seen upward mobility than older folk.

“The simple explanation is that (older respondents) have had more time to accumulate wealth, and also we know that in the past 50 years, Singapore has undergone massive improvements in mobility,” said Chew Han Ei, a senior research fellow at IPS and a co-author of the study.

However, it may not be only time that makes it more difficult for youths to accumulate wealth compared to the older generations.

Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong noted last year that among the concerns that Singapore faces is that social mobility is slowing, with those who have done well pulling further ahead of the rest due to their entrenched advantages.

Agreeing, Mr Ang Yew Shen, a 33-year-old director of sales at a wealth management firm, said that young people can still climb the social ladder.

They can succeed by thinking out of the box and knowing how to market themselves or their products through sales and on social media, for instance.

“Sometimes it’s not about the time, it’s about the person — whether they are willing to take on and seek opportunities out there,” he said.

Different perceptions of social class over time

The rungs on the ladder were divided into different brackets, where rungs one to four are classified as the lower social status bracket, rungs five to seven are the middle bracket, and rungs eight to 10 represent the upper class.

The study found that for those who put their childhood social status in the lower bracket, about nine in 10 report higher scores for their lives now, compared to just half from the middle brackets and 13 per cent from the upper class brackets.

More respondents also placed themselves in the middle and upper social class brackets now.

About half of the respondents reported that they were in the middle social class, while 11 per cent were in the upper class when they were children. But in their current lives, about seven in 10 said that they are in the middle social class and 19 per cent are in the upper class.

Conversely, 38 per cent of respondents reported being in the lower social class as children, but only 12 per cent stated that they have remained there. — TODAY