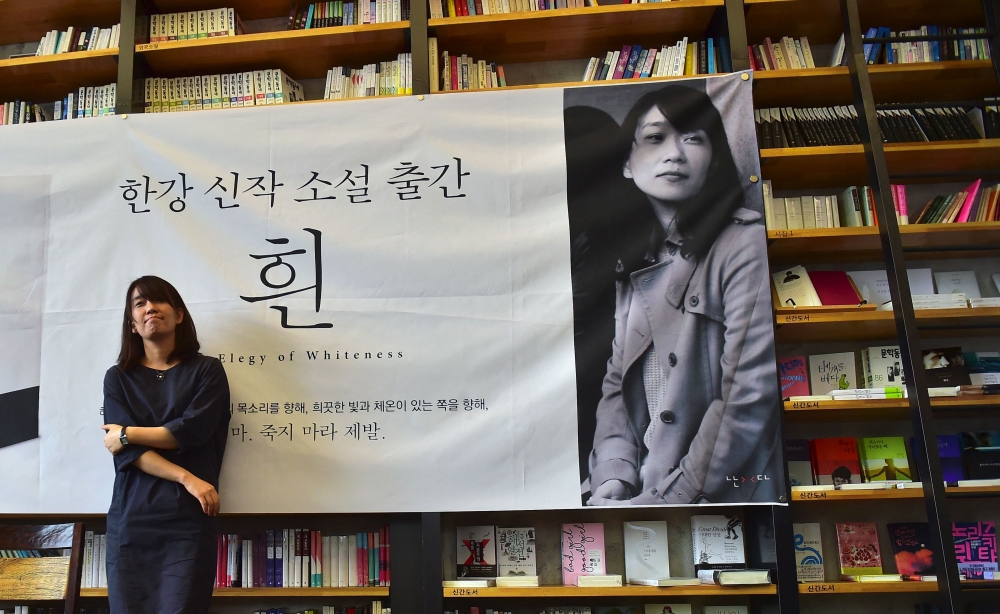

OCT 16 — “Did you hear about Han Kang’s father?” my friend asked me.

Han Kang, the recent Nobel Prize for Literature winner, and her father’s insistence on having a press conference though she herself didn’t want one?

Yes, of course I did.

It ended up becoming a discussion about South Korea, its toxic patriarchy, Han Kang and how much The Vegetarian perhaps mirrors her own lived experience as a South Korean woman.

In the book, you never get into the head of the protagonist.

Instead you see what her husband thinks, her brother-in-law thinks and how her own sister sees the situation.

The protagonist’s decision to stop eating meat is never treated as hers to make; instead her mother apologises to her son-in-law for his being inconvenienced and deprived.

Her father hits her, her mother again disrespects her autonomy by attempting to force feed her and it is never out of regard or concern, but anger at her not acquiescing, for insisting on departing from the norm of eating meat.

By attempting to leave behind the inherent violence of eating meat, instead she becomes a target for violence as she is sexually assaulted not once but a few times by more than one man.

This lack of autonomy and being punished for attempting to assert autonomy is a recurring theme through the book, and over and over again, the protagonist is told it would be better for her (and her husband, and her parents’ feelings) to acquiesce.

Yet, as that popular feminist saying goes, nevertheless she persisted.

The thing about The Vegetarian is if you take it at face value it seems more like a strange horror novel and the ambiguous ending might be unsatisfying if you like your stories to begin and end neatly.

Some say oh, it is one of her earlier less-polished works, you should read her other book(s) but I find I like The Vegetarian just fine, more than I thought I would.

I appreciate the way she depicts sexual assault as inherently devoid of reciprocal desire, as acts of violence and not to add drama to the plot, which alas, is a common failing among many writers particularly men.

Yet it also gets me thinking that actively choosing the high road, to do the good or better thing, is something people avoid because it is harder than doing nothing or instead being just plain mean.

I am ashamed sometimes of my own meanness and weakness, though I am rather unforgiving of meanness in others.

Yes, I was ornery to a doctor I knew, who said Malaysian medical conferences or any conference for that matter, should just not bother serving proper food.

Instead to reduce all the wastage as she called it, run events here the way it’s done in Western countries where you pay hundreds of dollars to be served bad coffee and maybe a sandwich in-between very long talks.

If I had to endure a conference and be served nothing but black coffee and maybe a stale croissant, I would probably stab the organiser with a fork.

But then I am Malaysian and 50 per cent of my brain cells are in my stomach.

She countered, “They still pay lots of money to go to those Western conferences, don’t they?”

My reply: “Why do we have to follow their s****y example?”

Why do we?

Why must we see people doing terrible, mean, inconsiderate things and consider that an example to follow?

I could apply that to world affairs or to my annoying neighbour who insists on throwing trash outside my bin, without even using a plastic bag.

We have choices and sometimes, those choices are terrible or have consequences that are even more terrible but I am grateful that for the most part, I do have autonomy.

Today, and I hope, every day, I choose what helps me sleep at night.

I will also live with the sad fact that my failing body is telling me, by its reactions to what I eat, that it truly wants me not to just read The Vegetarian but to be a vegetarian.

Perhaps that is the true lesson of my current cycle of suffering.