KUALA LUMPUR, July 14 — The recent Auditor-General’s report again highlighted the country’s public transport conundrum, as it flagged the poor ridership of both of Klang Valley’s mass rapid transit (MRT) systems.

MRT1, also known as the Kajang Line, recorded an average daily passenger rate that ranged from 10.8 per cent to 37.4 per cent between 2017 and 2023. The Putrajaya Line, which began operating in 2022, saw an average daily ridership of just 20,842 passengers that year, just a fifth of its target.

Operator MRT Corp attributed some of the drop to the Covid-19 pandemic. The company, wholly-owned by Prasarana Berhad, said ridership for both the lines will improve on the back of policies to discourage driving. Some of these policies, such as congestion charges and higher parking rates, have not been implemented.

However, pro-public transport advocates have touted the planned third and final MRT line, known as the circle line, as the likely end piece that would connect and integrate all existing rail systems.

What exactly is a ‘circle line’?

The name is usually based on what transport system experts call an orbital line, which is meant to “orbit” around the centre in a radial or polar network structure, connecting various radial lines at points other than a central hub

Singapore Transport Critic, a blog on transport systems, the main benefit of an orbital line is easing congestion at central transfer points by redirecting traffic around the city centre.

“Orbital lines typically are designed such that every node forms a connection with an outgoing radial line, maximising its potential as an added form of connectivity in a polar network,” according to the blogger.

Countries with fully developed public transit systems typically have a “circle line”. For example:

- The Circle Line of the London Underground, for example, runs a loop around the city’s central area. Almost all of the route on the circle line and its stations are shared with one or more of the three other lines (Metropolitan, District and Hammersmith & City).

- Singapore’s rail system applies the same logic, with its MRT circle line running a loop route around central Singapore to connect the North-South, East-West and North East Lines to the city.

How would the MRT3 Circle Line work here?

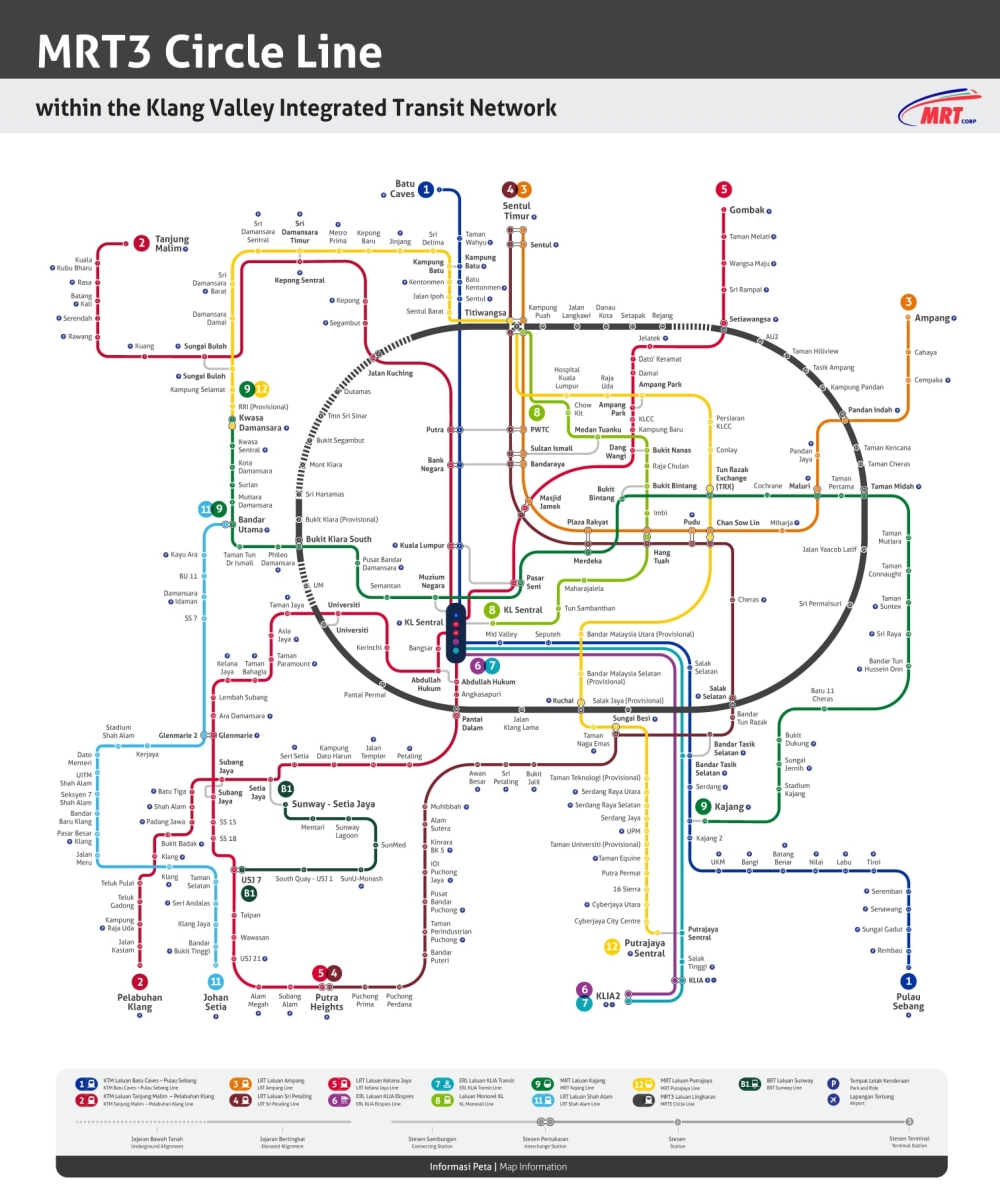

The planned line has a 51km alignment and will run along the perimeter of the capital city, connecting to existing MRT, LRT, KTM, and Monorail lines through 10 interchange stations.

There will be 32 stops along the line, with 22 elevated stations (39km), seven underground stations (12km) and three elevated provisional stations.

There will be 10 interchange stations: two on the MRT Kajang Line, two on MRT Putrajaya Line, two on the LRT Kelana Jaya Line, three on the LRT Ampang Line, one to the monorail, two with KTM Komuter and one with “city bus station”.

The circle line will mostly cover areas within Klang Valley that are close to one or two existing rail systems that are not directly accessible.

For example, with the circle line a passenger from Ampang could take the line and head straight to Mont Kiara, where it would also be connected with the Kajang Line via a new interchanging station at Bukit Kiara.

What’s the development status so far?

Transport Minister Anthony Loke Siew Fook said in January this year that the government wants to proceed with the project despite the Anwar government’s initial hesitation because of its massive cost, which is expected to be around RM1 billion per kilometre.

That same month, MRT Corp chief executive officer Datuk Mohd Zarif Hashim said the company is now focusing on the land acquisition process for the project, a process that is expected to take up to two years. The acquisition involves over 1,000 lots of land, with the majority being private lots, Zarif was quoted saying.

There is generally strong support for the circle line if not for the cost, which could reach up to over RM50 billion. Among the suggested alternatives are improving the bus system or building a tram system instead, both of which would cost substantially less.

However, the MRT Corp described the Circle Line as the “critical final piece to complete Kuala Lumpur’s urban rail network” that’s necessary to provide a comprehensive public transit system in the Klang Valley and its peripheries.

Policymakers also see the MRT systems as a catalyst for economic development apart from solving the valley’s worsening traffic problems. Urban connectivity is a key factor making cities like Tokyo, Seoul and Hong Kong thriving economic centres, something Kuala Lumpur has long lacked.

MRT Corp said the Circle Line also offers a chance to spur businesses in areas in the Klang Valley by opening up access to areas previously underserved by public transport systems.