- The proposed changes to citizenship laws will increase the number of people who have to apply for Malaysian citizenship.

- Malaysian Citizenship Rights Alliance (MCRA) says the Home Ministry is typically slow to process and unlikely to approve citizenship applications, which could worsen with the changes.

- The proposed amendment to reduce the age limit for certain citizenship applications from 21 to 18 will narrow the window for stateless children.

KUALA LUMPUR, July 12 — The Malaysian government will be creating a longer list of citizenship applications that it has to deal with if it changes citizenship laws by making more people apply for citizenship when they should automatically be Malaysians, the Malaysian Citizenship Rights Alliance (MCRA) has said.

While Home Minister Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution Ismail promised about three months ago to clear a backlog of 14,000 citizenship applications by year-end, but MCRA pointed out that the backlog will just grow back if the government pushes through with the proposed changes to Malaysia’s citizenship laws.

Suriani Kempe, one of MCRA’s spokesmen, said in a recent media briefing this month: “All he is doing is clearing of backlog, but if you are making more people applying for citizenship, you will refill your backlog quite quickly, right?”

But she said the Home Ministry has a “track record of slow processing time and low approvals” for citizenship applications, and that the government’s proposed law changes — via the Constitution (Amendment) Bill 2024 — would only worsen the waiting time.

“If more people have to apply for citizenship, it will mean more applications for KDN to process, longer processing times because more conditions and processes have to be fulfilled. That is the implication, that is the crux of the Bill,” she said, referring to the Home Ministry by its Malay initials KDN.

The longer it takes to process a citizenship application, the longer a stateless child will be deprived of rights — enjoyed by Malaysians — such as health and education, she said.

She said citizenship application processes could take up to 12 years and that many children who have applied do not get approved even by the time they reach age 21 — the current age limit for citizenship applications under the categories of “special circumstances” (under the Federal Constitution’s Article 15A) and for Malaysian mothers’ overseas-born children (Article 15(2)).

While the current home minister can show his dedication in making decisions for the backlog of 14,000 cases, Suriani said “there’s absolutely zero guarantee that the next minister will be processing this many applications”.

In other words, if the citizenship laws are changed, more people will now have to rely on the uncertain application process with an outcome that depends on who is the minister of the day, instead of the clear right to automatically be a Malaysian because of what the Federal Constitution says.

Another major change that the MCRA is objecting to is the government’s proposal to reduce the age limit for citizenship applications (for categories under Article 15A and Article 15(2)) from 21 to 18 years old, which means such children will lose out three years’ worth of chances and cannot apply to be a Malaysian under these two categories once they turn 18.

Suriani said another problem is that the government currently does not give any reasons when it rejects citizenship applications — including applications by Malaysian mothers for their overseas-born children.

“If the government is shortening the time where you can submit citizenship applications — it’s bringing down the age limit from 21 to 18; and on top of that you are not telling people why their citizenship applications get rejected, then people won’t know how to fix their applications to submit the correct application,” she said.

Referring to a March 25 news report where the home minister said citizenship applicants would be informed of the reasons for rejection, Suriani stressed the need for the government to have its processes in order and questioned how the public could trust the “entire amendment will not screw people over” if rejection reasons have not been given even after the minister’s remarks.

“When the government says ‘don’t worry, we will use rules and regulations to make sure people don’t fall through gaps’, none of the rules are made public, they don’t show the rules, so how are you going to make sure they are being enforced?” she asked.

Who will be affected?

In the Constitution (Amendment) Bill 2024, the government plans to delete the words “permanently resident” from a citizenship law (Section 1(a) of Part II of the Federal Constitution’s Second Schedule).

The effect of this is that it will remove automatic Malaysian citizenship rights for children born in Malaysia — to parents who are permanently here.

This means that instead of being entitled to be Malaysians, these children will now have to apply and it will be up to the government to decide whether they can be Malaysians.

While waiting for the government to decide on their citizenship applications, these children will be stateless or not citizens of any country in the world.

This is because their own parents are also stateless, as they are only known as permanent residents instead of Malaysians despite generations of being born and living here, including the indigenous communities (Orang Asli and Orang Asal) and third-generation ethnic Chinese and Indians.

Suriani said: “If the amendment is passed, the children of Orang Asli or Orang Asal who are stateless or have red ICs, they will now have to apply for citizenship. It will be up to KDN to decide whether to grant them citizenship and they may have powers to impose various conditions for the applicants.”

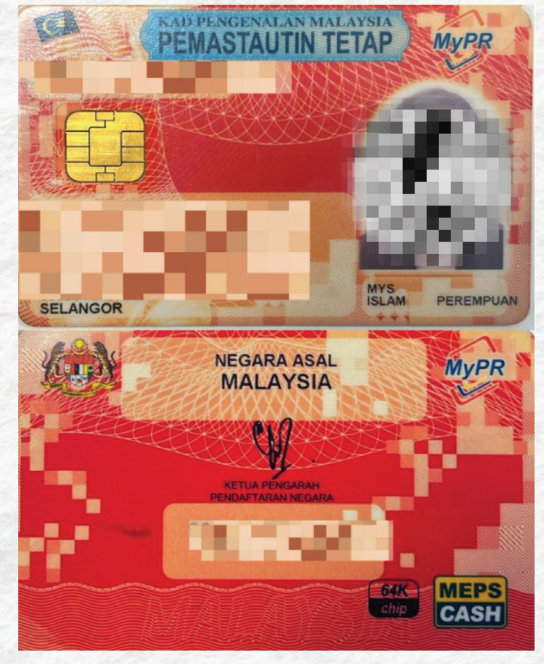

At the media briefing, MCRA’s spokesman Maalini Ramalo said the government has been inconsistently issuing red identity cards — or MyPR cards which recognises the cardholders’ permanent resident status — to different groups who are still stateless, including:

- Orang Asli, Orang Asal

- children born out wedlock

- children who were adopted

- pre-Independence cases (those born here before Merdeka Day, i.e. before August 31, 1957)

This means that the proposed new law change can affect any of them, and could also risk causing their statelessness to be passed down to their next generations, Maalini said.

Based on actual MyPR cards issued by the government to stateless persons, Development of Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA) Malaysia told Malay Mail that different information for “Negara Asal” (country of origin) have been seen on these cards, with some MyPR cards stating “Stateless” and others stating “Malaysia”.

Generally: Stateless ≠ refugees, migrants, foreigners

During the media briefing, MCRA also pointed out that the government tends to mix or lump three different things — refugees, migrants, stateless persons — into the same category.

But MCRA said refugees or migrants generally may be citizens of other countries and may have documents such as passports. As for stateless persons, they have genuine ties to Malaysia as they are born here or have Malaysian parents or were found and looked after by Malaysians; and are not foreigners or citizens of other countries and have never left Malaysia.

Maalini listed what people who are stateless are deprived of: "Citizenship is a doorway to other rights. Without citizenship, you can't access education, healthcare; you cannot work legally; because you don't have a passport and you don't have travel documents, you also cannot go anywhere. Which means if you are stateless, born in Malaysia, it's not like you can to another country make a new life there.

“You are not like a migrant, you are stuck here with zero rights and you cannot go anywhere, and right now the government's solution to this problem is if you don't have documents, we arrest you and put you in immigration centres. And then what?” she asked, saying that such individuals who cannot be deported as they have no country to be deported to would then just continue living in detention without rights.

While the government had tried to use foreigners in Malaysia as a reason to change the citizenship laws, Suriani said the country's existing citizenship laws do not give migrants and foreign workers access to Malaysian citizenship and changing those laws to tighten or limit citizenship conditions will still not change the status for these foreigners.

“They still won't be able to access, it doesn't affect them; it affects stateless Malaysians,” she said, and said any claims of foreign workers getting Malaysian citizenship would be due to alleged bribery or improper or illegal use of the system, and not because the country's citizenship laws are not strict enough.

“Amending the Constitution to restrict the rights of genuine Malaysians, ‘Anak Kita’, (our children) will not solve the problem of improper or illegal use,” Suriani said.

“By making it harder for ‘Anak Kita’ to apply for citizenship, this is how the amendments will increase statelessness in Malaysia.”

Sharmila Sekaran, another MCRA spokesman, said that it does not make sense to totally remove “permanently resident” from Section 1(a) in citizenship conditions in the Federal Constitution, and suggested that the government could instead amend it to “born in Malaysia and is permanently resident” and who are not citizens of any country. This would enable Malaysia-born children of such stateless persons who are permanently living in the country to be citizens.

Sharmila cautioned that if the government’s Bill is passed in its current form and becomes law, there would be a large group of people who will be shifted from the category of "citizenship by operation of law" to the category of “citizenship by registration”.

In other words, she said these people would lose their current automatic pathway to Malaysian citizenship, and have to go apply for citizenship — a process which is long, difficult, opaque and arbitrary with no reasons given for rejections and applicants do not know when decisions will be made.

For example, she said there have been cases where a family might see siblings having different outcomes for their citizenship applications: one child may be a Malaysian citizen by registration while the other sibling’s application is rejected, despite both of them having the same circumstances.

What’s next?

To become law, the Bill has to get two-thirds approval from all lawmakers in the Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara (at both the second and third readings of the Bill), as it involves changes to the Federal Constitution.

The Bill has yet to be voted on in Parliament and has to become law.

The Bill is scheduled for second reading during this current Dewan Rakyat meeting (which ends July 18). It is unclear if it will proceed to be debated on, as an MP had applied for the Bill to be referred to a parliamentary special select committee first.

Recommended reading:

- Malaysia’s citizenship law amendments: What it does and why it matters

- ‘Invisible’ in Malaysia: Why are people born here stateless and will the govt’s citizenship proposals fix or worsen the problem?

- Govt tables Bill to help Malaysian mothers; but wants to stop permanent residents’ children from getting automatic citizenship

- After parliamentary debate on citizenship amendments deferred, MCRA hopes to find joint solutions with Putrajaya