KOTA KINABALU, June 29 — Type in “Bajau Laut” and Google will show you hundreds of photos of joyful, carefree kids tumbling into clear turquoise waters atop coral reefs or smiling people living on their home boats or stilt homes overlooking the same sea.

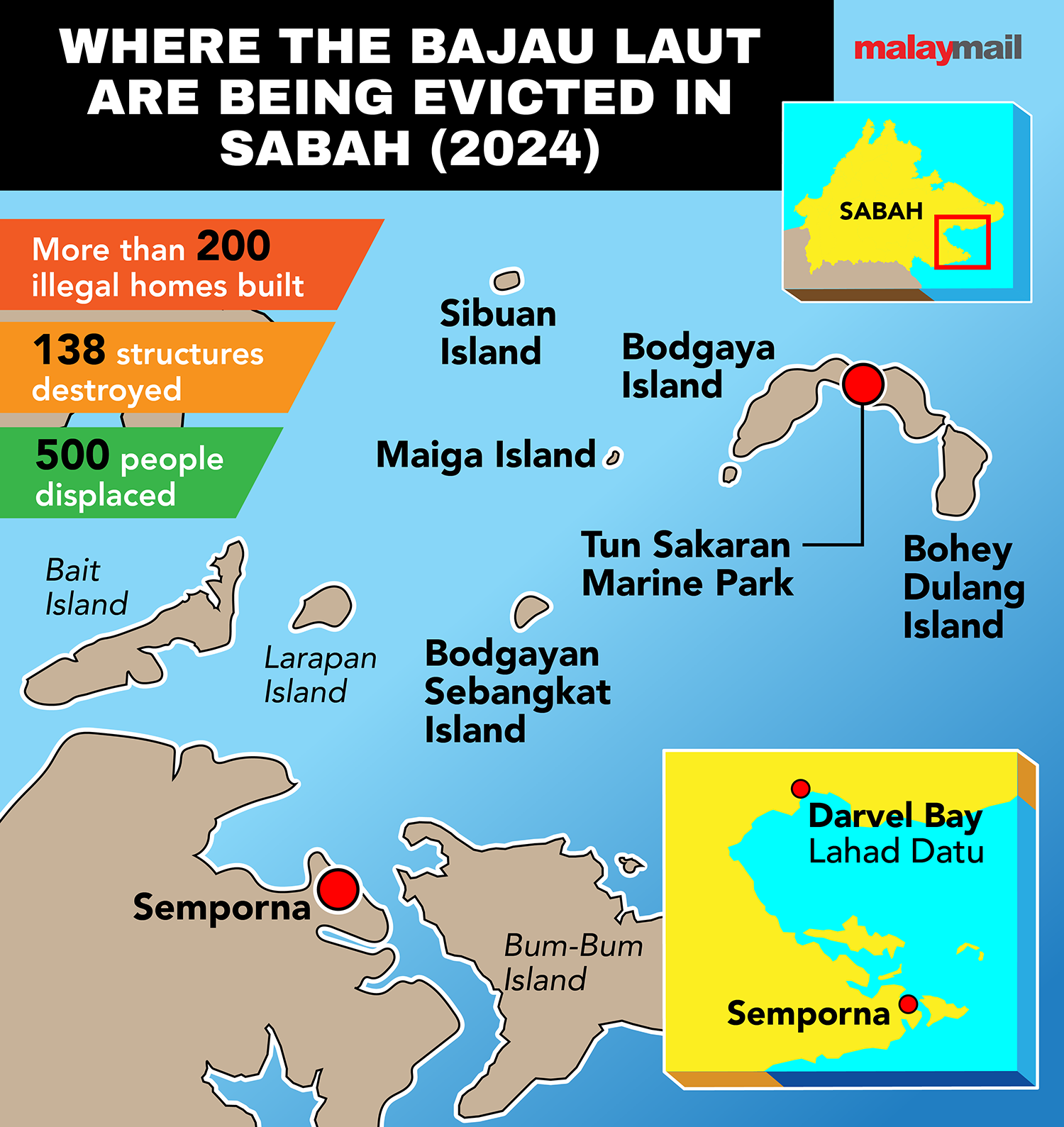

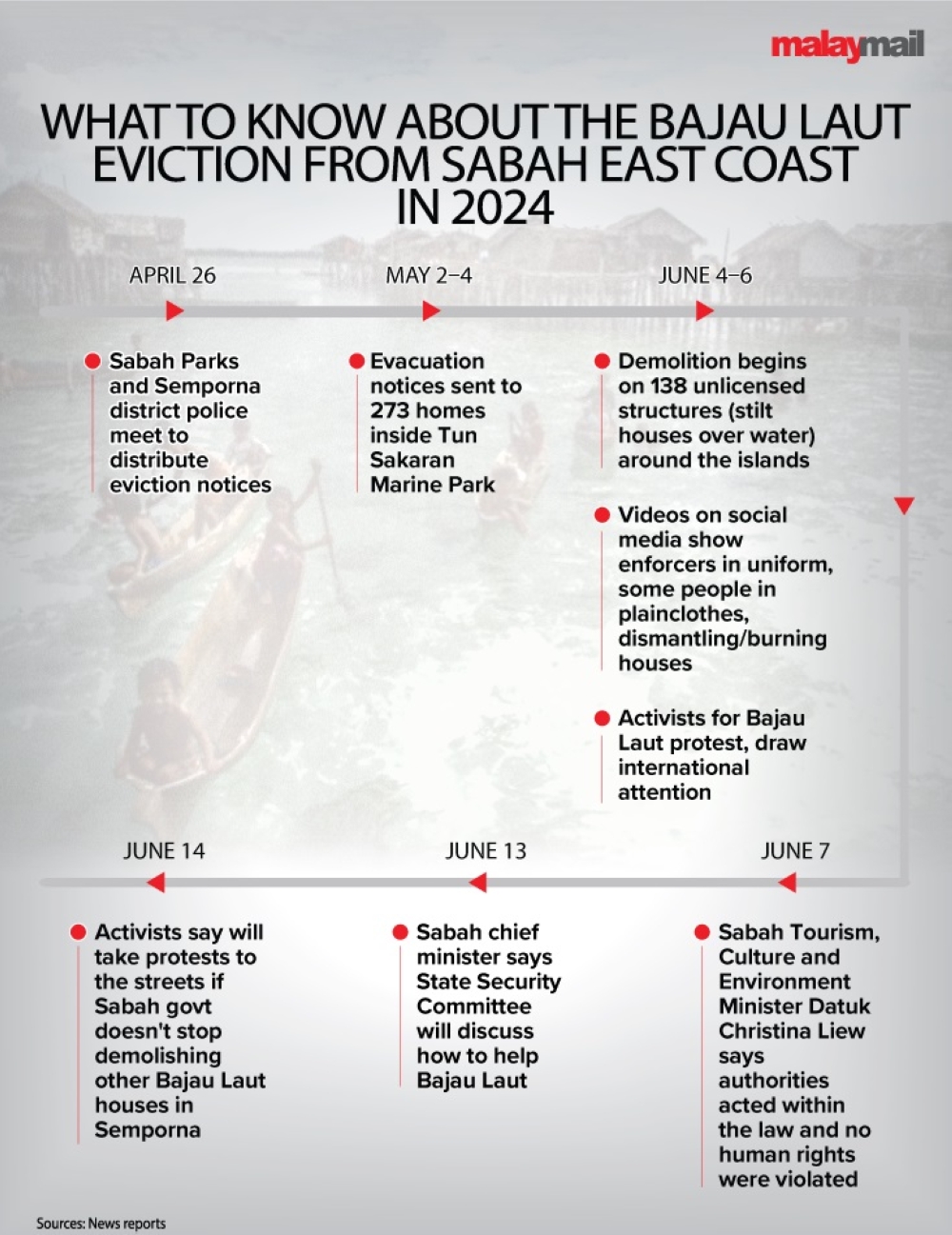

But the reality is far less picturesque and closer to the recent controversy of the forceful eviction of the Bajau Laut from their homes in the highly touristy Tun Sakaran Marine Park off the town of Semporna on Sabah's east coast.

The traditional homes housing families are now seen being sawed off their stilts, pushed down by men or taken down by boats manned by enforcement authorities.

Activists and advocates say that the Bajau Laut do not deserve the treatment they received after living in the Tun Sakaran Marine Park region, some for decades; but many others — the public, tourists, local businessmen — may have a different view.

The sea-faring, coastal Bajau Laut people have a history of roaming the Sulu Celebes seas around Sabah, the southern Philippines and Kalimantan Indonesia for centuries, but they belong to none of the countries.

Their self-sufficient way of life means independence from government systems, which also means no access to healthcare, education, basic infrastructure and identification. They speak their own dialect and do not subscribe to modern lifestyles.

Some have adapted to becoming land-based but a good number of them still roam the sea coasts in hopes of preserving the only culture they know — fishing and relying on the sea and coasts for their livelihood.

But depleting resources means that the Bajau Laut are made more vulnerable and their poverty has resulted in an unsavoury reputation.

Some of the children who have not been taken in by independent schools, roam the nearest town, sometimes selling fresh seafood and sometimes begging from tourists.

Their lack of access to healthcare can make them prone to disease and illnesses and increasing poverty may lead to activities such as fish bombing and exploitation by smugglers and kidnap-for-ransom groups.

With no citizenship, they may have no allegiances; and Malaysian authorities have sometimes portrayed them as being insiders to major crimes.

Activists for the stateless argue that there has been no evidence of such wrongdoing by the Bajau Laut and instead advocate for their acceptance into the system.

Actions such as the recent eviction is a clear indication of how the Bajau Laut community have been sidelined and discriminated against for decades with no regard for their culture or future.

NGOs argue that Sabah’s Parks Enactment 1984 of which Tun Sakaran Marine Park is declared under, provides for existing native customary rights but those rights are trampled on by land owners who are looking to develop the island for tourism purposes.

It remains unclear at this point whether or not the land has been earmarked for development.

But with no education or awareness, or even illiteracy, the Bajau Laut will always be on the losing end to any party.

Recommended reading: