KUALA LUMPUR, June 29 — The recent uproar in Sabah surrounding the Bajau Laut tribe, sometimes known as the Pala’u has thrust this often persecuted community back into the spotlight.

The latest conflict between the state and the Bajau Laut in Sabah centres around the tribe’s eviction from their home.

But this latest episode goes back a long way and really highlights the challenges to indigenous rights as well as the state’s guardianship role.

Who are the Bajau Laut?

Predominantly dwelling in the waters of South-east Asia, notably in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia, the Bajau Laut, often dubbed the “sea nomads” or “sea gypsies”, are celebrated for their extraordinary diving prowess and profound affinity with the ocean.

Traditionally, they inhabit houseboats or stilt houses erected above the water, their livelihood hinging on fishing and foraging on marine resources.

While some have transitioned to land settlements, others steadfastly cling to their nomadic existence at sea. Both often walk blurred lines of official residency of any nation.

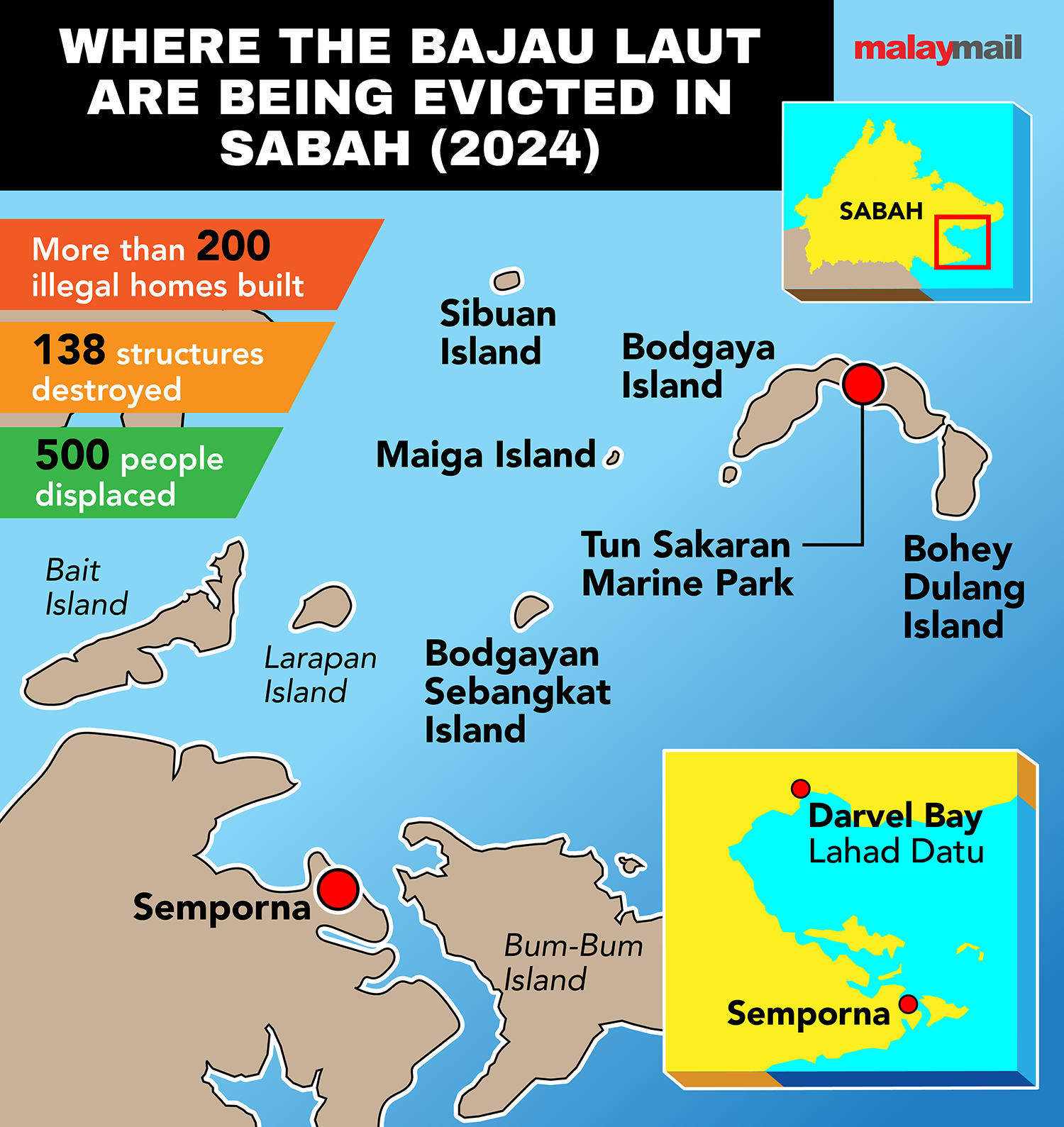

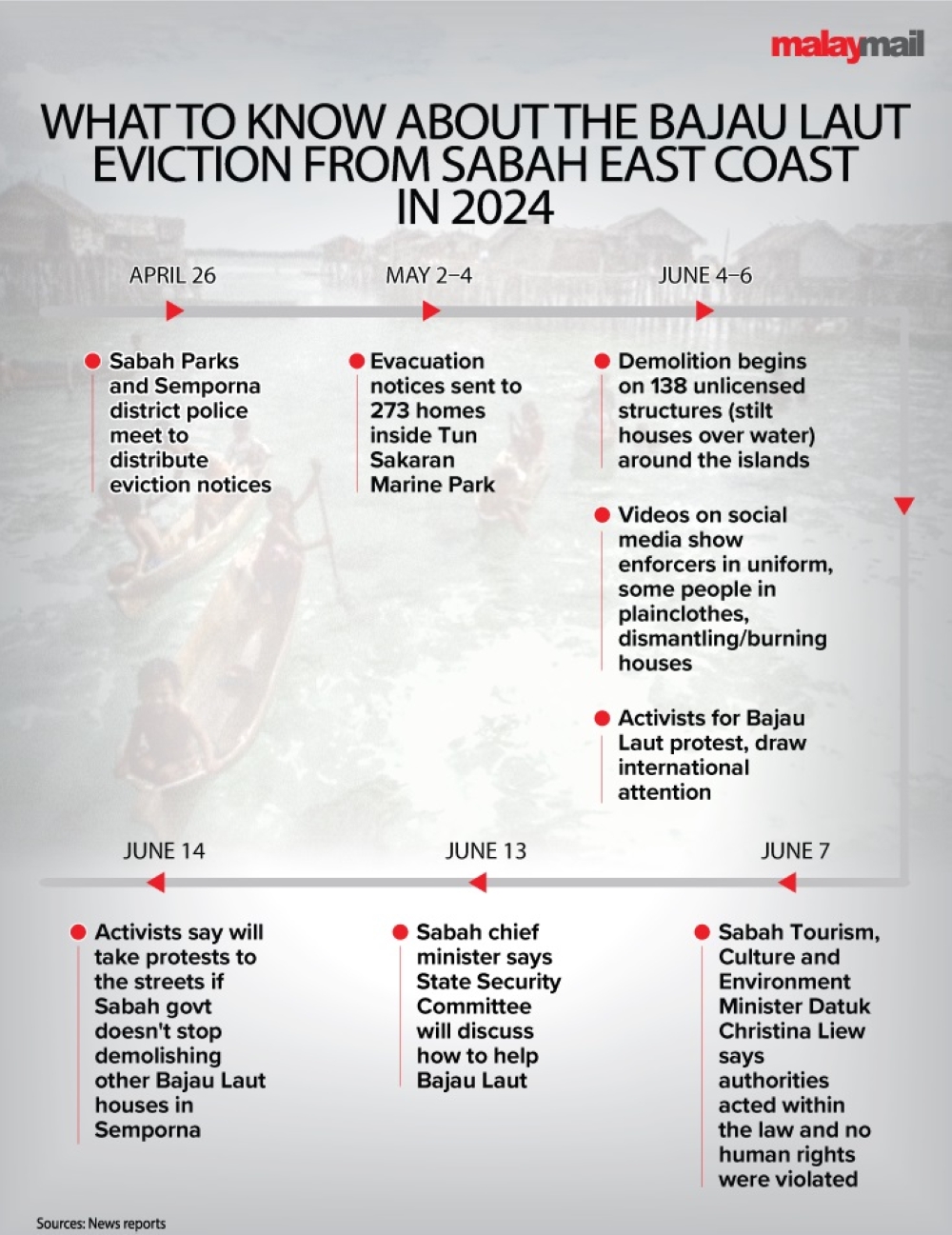

Recent tensions flared when authorities undertook the demolition and incineration of dwellings within the Tun Sakaran Marine Park on the east coast of Sabah where they are sometimes shunned even by the local, naturalised Bajau Laut who have taken up modern civilisation.

Why is the Sabah government going after them?

The Sabah authorities have a duty to fortify national security and safeguard the environment. As such the move to evict squatters was a response to the proliferation of unauthorised structures within the marine park's confines.

State Tourism, Culture, and Environment Minister Datuk Christina Liew underscored that these actions were necessary to quell security threats and curtail environmental violations.

However, the operation, encompassing regions around Bohey Dulang, Maiga, Bodhgaya, Sebangkat, and Sibuan Island, underscored the myriad challenges confronting the Bajau Laut community.

Clashes between nomads seeking a permanent home and the state

Many, despite the looming spectre of deportation, regard locales like Semporna, Sabah, as their home, even though their stateless status renders them susceptible to being labelled as illegal immigrants or undocumented migrants.

Birth registrations are often foregone by wary parents, fearing reprisal, thereby restricting their children's access to education and healthcare services.

While Indonesia and Malaysia have informally agreed not to detain children while in school, they remain vulnerable to arrest beyond school premises.

Criticism has also been levelled at the Bajau Laut for unsustainable fishing practices, including blast fishing and cyanide fishing, which inflict harm on marine ecosystems.

Furthermore, clashes over land rights, resource allocation, and encounters with local authorities have added to their woes.

Calls from human rights groups and NGOs echo for the cessation of evictions in Semporna and for increased aid provision to the Bajau Laut.

Advocates stress the imperative of dialogue and negotiation to forge sustainable solutions that uphold the dignity and well-being of this resilient community.

Recommended reading: