KUALA LUMPUR, March 30 — Somewhere in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, modern folklore tells of a story of a million worth of real Malaysian banknotes hidden in plain sight.

Yet such a priceless treasure (and definitely not folklore at all) can be found nestled behind an acrylic tunnel wall within Bank Negara Malaysia’s (BNM) Museum and Art Gallery at Sasana Kijang along Jalan Dato Onn.

Siti Melorinda Khuzaina Sakdudin is one of its designated custodians to ensure its safekeeping.

“The RM1 million tunnel comprises early Malaysian banknote denominations and series including the latest (issued in 2012) which forms part of the greater Children's Gallery,” Siti Melorinda explained to Malay Mail in an interview recently.

As BNM’s Children’s Gallery and Art Gallery curator, the money tunnel is one of the few exhibits the 45-year-old curates, as part of her responsibility in ensuring the central bank’s role in the nation’s economic development and financial landscape are well communicated to museum-goers.

In an ever-changing world, museums offer a static space to reflect on our civilisations’ transformations and engage with various forms of human expression across different ages and cultures, and BNM’s Museum and Art Gallery is no exception.

Once taking on a traditional role in preserving and showcasing relics and artworks, museums have in recent years dynamically evolved into spaces for education, dialogue and inspiration.

“As curators here, I believe our role is about planning and executing exhibitions of our collection using the bank’s content which we want to share with the public and the message intended.

“As for the Children’s Gallery, my contents are related to the simpler parts of finances such as learning what is money and its history for children to easily understand — which I curate through engagements with other curators here to make a simplified version of their exhibits for them to interact with,” she said.

She explained that the Children’s Gallery is filled with hands-on games and activities based on the concept of “Save, Spend and Share”, a unique informal learning venue for elementary and primary school kids.

The galleries Siti Melorinda curates are two of six permanent themed galleries in BNM’s Museum and Art Gallery, the other four being the Bank Negara Malaysia Gallery, Economics Gallery, Islamic Finance Gallery and the Numismatics Gallery spread over four floors.

Noting that curatorship was more than just artefacts cataloguing, Siti Melorinda said being a curator posed its challenges and proper credentials are necessary to navigate such a specialised area of interest.

“Honestly, I have never dreamed of becoming a curator since I came from an accounting background but I have always found myself working in the arts and culture field upon my graduation from university,” she shared.

Inspired by her mother who had exposed her to the arts and culture since young and one local archivist Nur Hanim Khairuddin, Siti Melorinda found herself working at Akademi Seni Budaya dan Warisan Kebangsaan (Aswara) before eventually joining BNM’s museum department 18 years ago.

“I think the most important thing is passion, it helps you a lot. If you have an interest then it makes it easier to learn and pick up all the things, such as networking with other curators, conservators, organisations, and collectors either private or institutions-based because we have to choose the right artwork.

“As for the children, it was quite difficult for my team because we have to determine simpler words to be conveyed, so yes, an understanding of a suitable level of language to ensure our visitors pick up our content as well,” she said.

Among the toughest challenges she had faced came from the complexity of organising an exhibition which included obtaining consent from collectors, and logistical elements to ensure collections were delivered punctually in pristine collection.

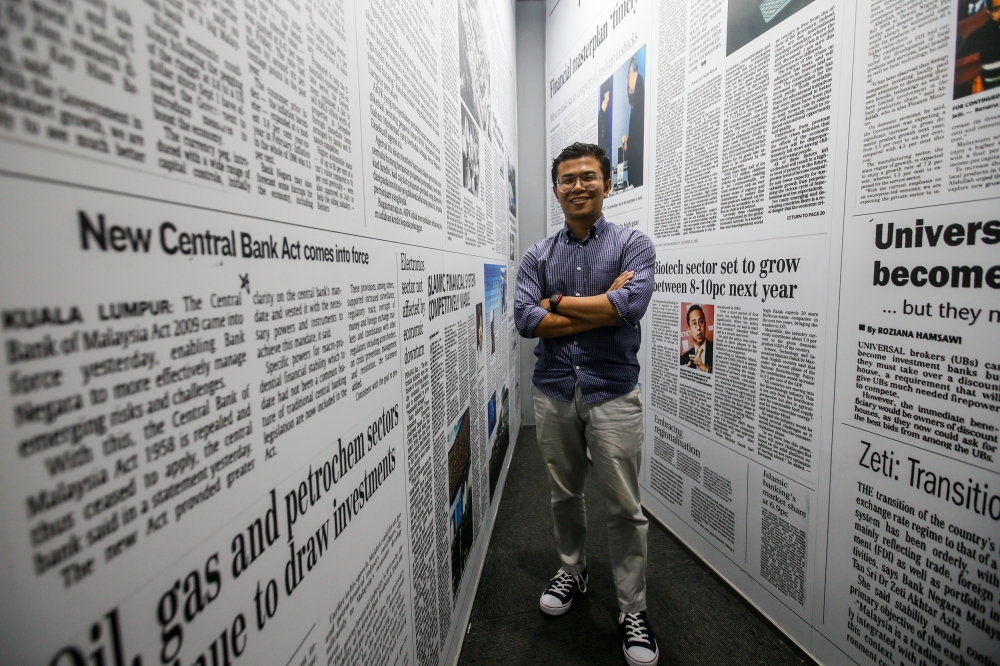

Like Siti Melorinda, fellow colleague Amirul Asyraf Ahmad Sabri too found himself in the most unexpected position as a curator just over two years ago when he started his career in 2017.

“That time when I was young, I thought museums were for historical things and for old people but then as time went by and since I was already working with BNM and my passion for educating others, I found that being a curator for BNM is not just about history, but bridging the bank’s current mandate and the nation’s issue.

“The way I see it, curatorship in a museum is beyond cataloguing artefacts and there are a lot of ecosystems you can venture into,” the 30-year-old who majored in accounting and finance said.

Curating for both the Economics Gallery and Islamic Finance Gallery, Amirul Asyraf too had his misconception in the beginning as he had accompanied his father who used to work in the National Museum as an adolescent.

“Curators, in general, have to know their artefacts and documents, in terms of the country’s economic and Islamic finance history as our mandate is to educate the public of BNM’s role.

“So there is also how we are going to explain this, using relevant topics and educate the public on what BNM has done for the country,” he added.

Among others, Amirul Asyraf said the trickiest part of being a curator is the procurement of artefacts and archived documents which have to then be curated and conform to the intended narrative.

As custodian to his galleries, Amirul Asyraf said the challenge lies in how one communicates and translates something intangible as economics and Islamic finances are both heavy concepts for the general public.

“If you look at a typical traditional museum, you would use descriptive language, but what we are trying to do here is to break the rule in a good way where we can change the tone to be closer to kids and the layman,” he said.

Citing his experience working in one of BNM’s core departments, Amirul Asyraf curators have had to strive towards adapting to the changing societal interests and technological advancements.

Having said that, Amirul Asyraf also revealed he shares a similar sentiment with Siti Melorinda that one requires passion in such a specialised field of work.

Apart from passion, Amirul Asyraf also said communication skills in both verbal and written form are also required to accurately interpret contents for eventual display to visitors.

“Especially passion in educating, so if you are passionate no matter what subjects are thrown at you, you will study it first and then make it fun.

“Lastly, adaptability and creativity because you see the world is constantly changing and the pace is very fast,” he said.

Notwithstanding the hurdles they faced, both Siti Melorinda and Amirul Asyraf said seeing their curation work become a topic of interest for people’s discussion is something every curator strived to be.

Moving forward, both curators told Malay Mail of their intention to continue educating the public through their curated works in the BNM Museum and Art Gallery.

“If people start talking about your exhibition, and they start sharing and you have teachers bringing their children and then use your exhibit’s content to teach, I think that is something I would feel very happy about.

“Be your trendsetter, if you find something new that others have not done, it is good for you,” Siti Melorinda said towards the end of the interview.

“Even though I am still quite new, my wishlist is how do I change an exhibition where people start talking about it and how to make an exhibition with its content about the central bank to be translated into all things daily or activities,” Amirul Asyraf added.