KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 8 — Ever wondered why the High Court on Monday granted a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA) to release Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi from all 47 charges in his Yayasan Akalbudi trial, instead of acquitting him?

Here's what legal experts have told Malay Mail on how the law works in Malaysia: After the attorney general (AG) exercises his discretion under the Federal Constitution's Article 145 and the Criminal Procedure Code's (CPC) Section 254 to discontinue an ongoing trial, the courts would then have only the option of either ordering a DNAA or an acquittal.

The experts said the courts cannot reject the AG's decision to drop the trial, but must make either one of those court orders.

A DNAA would allow the prosecution to charge the accused with the same charges in the future, as opposed to an acquittal where the prosecution cannot bring the accused back to the court to be charged with the same charges.

So how do the courts decide on these two options once the AG discontinues the trial? Here's a quick summary:

1. After the AG decides to discontinue the trial, under what situations would the court then grant a DNAA or an acquittal?

The short answer: Whatever the facts in each case, the legal test is whether there are "good grounds” or good reasons for why the courts should grant a DNAA instead of an acquittal.

Former Malaysian Bar president Ragunath Kesavan said the prosecution could withdraw charges against an accused by either saying it or indicating by its conduct (such as by the prosecution not turning up in court), with the court then having the power to decide whether to order a DNAA or acquittal.

Saying that there is no fixed list of reasons why a court would decide whether to acquit instead of granting a DNAA, Ragunath said it depends a lot on the specific facts in each case, such as where the accused is old; the witnesses are aged or deceased; where the trial has gone on for a long period and it would be prejudicial to the accused.

“In most situations where the matter has started, witnesses have been called, the courts would normally give an acquittal, unless there are exceptional reasons why there should be a DNAA.

“So in this case, based on the number of witnesses and stage of proceedings, it should have been an acquittal,” he told Malay Mail.

Mohamad Hafiz Hassan, a law lecturer at Multimedia University who teaches criminal procedure, said it appears that the main consideration is whether the prosecution has indicated that they do not wish to proceed with the case at all, referring to the acquittal of Lim Guan Eng in 2019 after the public prosecutor invoked Section 254 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

Criminal lawyer Tiara Katrina Fuad said the situations where the court will decide to grant a DNAA would differ from case to case, but said the prosecution must show “good grounds” on why the court should grant a DNAA.

Being part of the legal team involved in the 2022 Federal Court case of Vigny Alfred Raj a/l Vicetor Amratha Raja v Public Prosecutor which is currently Malaysia’s leading case on the issue of DNAA, Tiara Katrina said: “The law is and has always been that the burden is on the public prosecutor to justify a DNAA, to provide ‘good grounds’ to justify a DNAA.

“Case law has interpreted what good grounds means, it means a temporary impediment which can be surmounted within a reasonable period of time, that's the test.

“So if the Public Prosecutor can provide good grounds, i.e. it can show the impediment to the prosecution they are facing right now is temporary and they can surmount it within a reasonable period of time, that is a basis for entering a DNAA. If they cannot provide good grounds, then the court should order an acquittal, that's the case law,” she said, agreeing that good grounds would include “cogent” reasons.

The Federal Court case judgments can be found here and here.

When applying for the High Court to only temporarily release Zahid from the 47 charges through a DNAA instead of an acquittal, the prosecution had given 11 reasons for a DNAA.

Afterwards, when the High Court decided to grant a DNAA in Zahid’s case, the judge said the prosecution had given “cogent reasons” for why a DNAA should be granted.

These are the same “cogent reasons” that the AG’s Chambers had on Tuesday mentioned in its brief two-paragraph statement, where it referred to the High Court as having said the prosecution had given “cogent reasons” for its application for a DNAA. The AGC did not say why it decided to discontinue the trial against Zahid.

Note: Remember, unlike the AG’s decision to discontinue the trial where the AG is not legally required to give its reasons, the court would only decide to give a DNAA — instead of an acquittal — if the prosecution gave good reasons.

2. Will you start from zero if given a DNAA and ‘recharged’?

Short answer: No. You won’t have to restart the case.

Hafiz referred to Section 254A, which was introduced into the Criminal Procedure Code through a 2010 amendment and which came into force on June 1, 2012.

Under Section 254A, when an accused person has been given a discharge by the court and is recharged for the same offence, the trial “shall be reinstated and be continued as if there had been” no order given to discharge the person from the case. But it will only apply where witnesses have been called to give evidence in the trial before the court gives its order to discharge the accused person.

Tiara Katrina said Section 254A would automatically apply when a person who was given a DNAA is charged with the same charges again as the provision is mandatorily worded with the word “shall”, and that the reinstated trial will start where it last left off.

“It should be before the same judge, it should be in the same court, with the same bail conditions. It will be as though the trial never stopped,” she said, adding that there have been such court cases where Section 254A was applied.

“There's a qualification, Section 254A(2), it applies only when witnesses have already been called, which would apply in Zahid's case, if he's recharged,” she said.

With Section 254A, the court would not have to hear the same witnesses who had already testified all over again, and would just move on to hearing the next witness in the witness list, she confirmed.

She said for example that if a previous witness did not finish testifying before the granting of a DNAA, this witness would be asked to continue testifying in the now-reinstated trial.

Ragunath said there have been many cases where Section 254A was used, noting for example that these were used during the Covid-19 pandemic when trial has started but a witness is overseas and cannot come into Malaysia due to travel restrictions and where a DNAA was granted before the trial was reinstated.

3. Why can't a person be charged again on the same charges once they have been acquitted?

Short answer: The double jeopardy rule.

Hafiz cited the Federal Constitution’s Article 7(2), where a person who has been acquitted or convicted of an offence must not be put on trial again with the same offence, except where a court — which is higher than the court which acquitted or convicted him — quashes the conviction or acquittal and orders for a retrial.

He said the Federal Court had in the 2010 case of Palautah a/l Sinnappayan v Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri, Malaysia said the protection under Article 7(2) against being put on trial again only applies to criminal offences.

“It is a common law rule that no man should be placed in jeopardy twice. The rule has been codified in Section 302 of the Criminal Procedure Code,” he said.

Citing Article 7(2), Tiara Katrina said it is a constitutional prohibition to put someone who has been acquitted on trial for the same offence, adding that this is because of the principle of "double jeopardy”.

“It’s a fundamental principle of fairness that a person cannot be repeatedly tried for an offence for which he was previously acquitted or convicted, and it’s recognised in virtually all jurisdictions around the world,” she said, adding that Article 7(2) does not cover situations like DNAA.

On Monday, Zahid's lead defence lawyer Datuk Hisyam Teh Poh Teik said an appeal will be filed at the Court of Appeal against the High Court's DNAA decision in order to seek for an acquittal. As of Wednesday morning, Malay Mail understands that the appeal had yet to be filed.

Note: The DNAA in Zahid's case after the AG dropped the charges was when Zahid's trial had yet to conclude as his lawyers had planned to call in 17 more defence witnesses to testify in his favour, while Kinabatangan MP Datuk Seri Bung Moktar Radin's acquittal by the High Court involved different court procedures and laws.

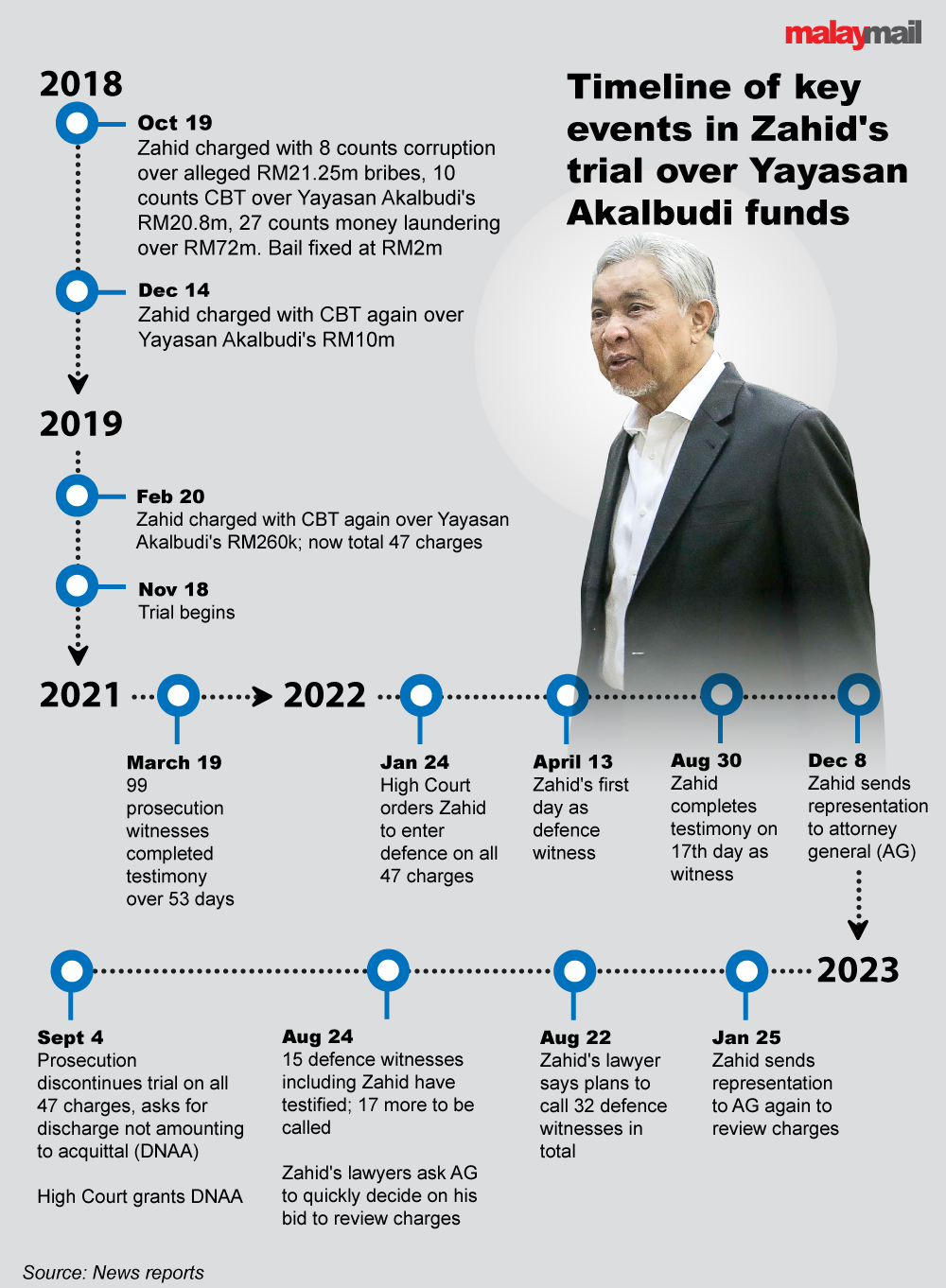

On Monday, the prosecution decided to discontinue and drop the Yayasan Akalbudi trial against Zahid — which resulted in the High Court granting a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA) on Zahid for all 47 charges he faced.

Zahid, who is also Umno president and Barisan Nasional chairman, faced 47 charges in this case, namely, 12 counts of criminal breach of trust in relation to over RM31 million of his charitable organisation Yayasan Akalbudi’s funds, 27 counts of money laundering, and eight counts of bribery charges of over RM21.25 million in alleged bribes.

The move to not pursue the trial was derided by both sides of the political divides, with Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim later stressing that he was not involved in the decision.

The Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) also defended its decision to discontinue the trial by saying that the prosecution had argued for a DNAA based on “cogent” reasons. In granting a DNAA in Zahid's case, the High Court had said the prosecution had given “cogent reasons” for why it applied for a DNAA.

The AGC's statement did not state why the prosecution decided to withdraw all 47 charges or to discontinue Zahid's trial.

This is Part 2 of Malay Mail's series on how the law works for discontinuing of trial, discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA), acquittals and why institutional reforms are necessary. Read Part 1 here.