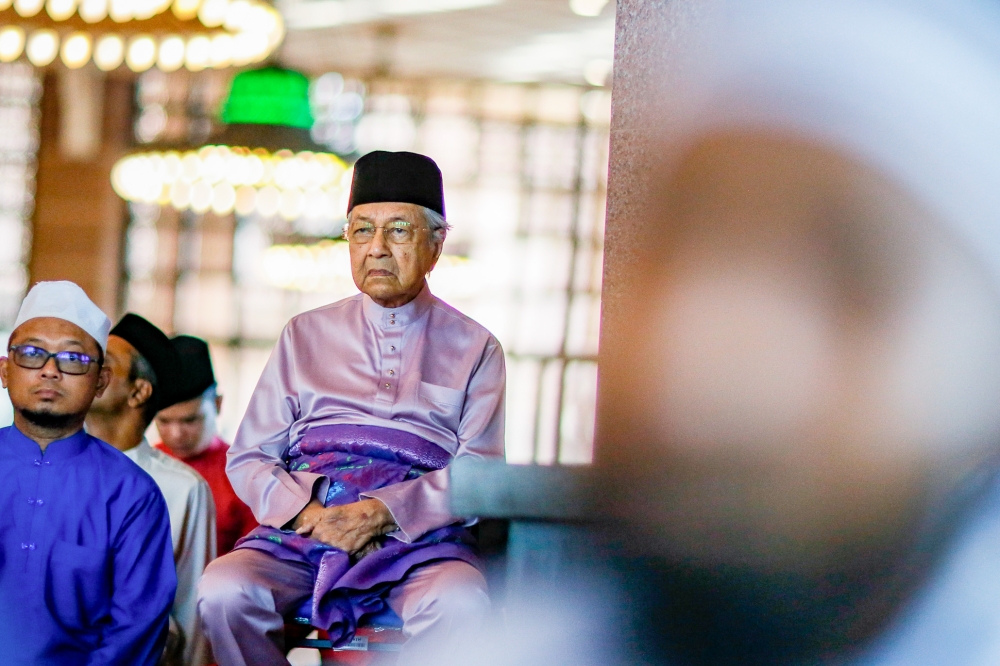

KUALA LUMPUR, July 14 — Quiet after leaving Parti Pejuang Tanahair and Gerakan Tanah Air, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad threw himself back into the media spotlight by claiming that promoting a multi-ethnic Malaysia is unconstitutional.

The two-time former prime minister justified his claim by pointing to the alleged “Malayness” of the Federal Constitution, which he said has never mentioned that Malaysia is meant to be multiracial.

His remark has since been backed by some in the pro-Malay lobby including his former party Pejuang, but how accurate is this assertion?

Contrary to the claim, Malay Mail’s check of the Constitution found that the word “Malay” is explicitly mentioned mostly to refer to the Malay language and the Malay Peninsula.

This is especially on several Articles regulating citizenship such as Articles 16, 16A and 19 — where citizens are required to have a sufficient or elementary knowledge of the Malay language.

As for the Malay ethnic group, there are three instances where it is referred to, the first being the jurisdiction of the Parliament to enact laws in Article 76. Clause (1)(2) of the Article states that the Dewan Rakyat cannot enact laws over “any matters of Islamic law or the custom of the Malays”.

Additionally, Article 89 handles the specific matter of Malay reservations, while Article 90 also handles Malay holdings in Terengganu.

The one Article commonly cited by pro-Malay groups is Article 153 which handles reservation of quotas in respect of services, permits, and so on for Malays and East Malaysian natives.

Finally, Article 160 provides the definition of “Malay”: “a person who professes the religion of Islam, habitually speaks the Malay language, conforms to Malay custom”.

Pro-Malay not equal to anti-multiracialism

Speaking to Malay Mail to comment on Dr Mahathir’s remark, constitutional lawyer Andrew Khoo said while the Constitution is pro-Malay in certain provisions, it is clearly not being anti to other ethnic groups.

“It is not binary. It’s not a zero-sum game. The Constitution contains certain pro-Malay provisions, but the Constitution itself as a whole is pro-Malaysian.

“It is pro-Malay in a sense that it protects Malay land, and places the Malays in a special position together with the natives of Sabah and Sarawak and then there is some protection of the Malay Regiment,” Khoo said, referring to Article 153.

Referring to Dr Mahathir and Pejuang information chief and lawyer Rafique Rashid Ali who backed the former, Khoo said it seems that there is a misunderstanding and misrepresentation of what is in the Constitution.

“The Constitution gives a certain degree of privilege and protection, to Malay land, it’s very clear — it’s Malay land — and then also to Malays and natives of Sabah and Sarawak. But it does not mean that it then takes away protection from other groups of people.

Offering more explanation, International Islam University of Malaysia’s law lecturer Nik Ahmad Kamal Nik Mahmood said the mention of “Malay” in the Constitution was the result of independence negotiations led by a Malay nationalist party Umno, along with the Malay Rulers.

“The draft Constitution contained special provisions on the special rights of the Malay, Malay language as the official language, the special position of the Malay Rulers in the Conference of Rulers (one of the rulers would be Yang di-Pertuan Agong), provision for Malay reservations, and privileges in certain aspects.

“To say it is pro-Malay and at the expense of other races is not correct as rights of other races are protected and it included citizenship, religious freedom, and enjoying the other rights as citizens of the country,” the professor said.

How the Constitution is ‘colour-blind’

Khoo said the Constitution does not make a distinction within the three branches of government — the executive, the legislature or the judiciary — as there is no test required barring certain ethnic or religious group from holding positions in them.

This makes the Constitution not simply pro-Malay, but also pro-Malaysian, Khoo said.

“There is no requirement for you to be of any one particular race or religion, in order to be a member of the executive, legislature, or judiciary. Your right to life, your right to all the fundamental liberties, in Part Two of the Constitution is not dependent on you being of a particular race or particular religion.

“In other words, the Constitution is colourblind. It’s race-blind,” he said.

Khoo however conceded that there is no mention in the Constitution that Malaysia is a “multiracial” or “multiethnic” country.

“But if you read the entire Constitution, you will see that broadly speaking all the rights and liberties and all the privileges like voting and things like that, is race-blind, it’s ethnicity-blind.

“All we want to say is that the Constitution prohibits discrimination on the basis of race and religion, there are certain provisions that protect certain aspects of Malayness, like Malay reserve land, equality in terms of job, but otherwise all the other rights or benefits of citizenship are available to all Malaysians regardless of race, regardless of religion,” he said.

Similarly, Khoo said the Constitution does not explicitly mention that Malaysia is a secular state.

“Malaysia is not a secular country because we have a [religion of the federation], so we cannot be a secular country, but then again they fail to understand, what does it mean to be a secular country?

Khoo again pointed to how the organs of government have no race or religious requirement, nor does one have to be a Muslim to be elected as an MP or a judge.

“In that sense, we are multi-ethnic because we can be any race, and any religion and we can still be appointed and elected to offices within the government. That is the test of a secular country and test of a multi-ethnic country,” he said.

Would a guarantee for equality threatens the Malays?

The Constitution does however protect Malaysians regardless of their ethnic background.

Article 8 which guarantees equality states that “All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law.”

Specifically, Clause (2) of the provision reads “there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent, place of birth or gender” when it comes to law, appointment to office, holding property, or establishing a business.

However, Khoo argued that this equality ultimately is not absolute since it is bound by other exceptions in the Constitution, such as Article 153 — therefore guaranteeing the special rights enjoyed by the Malay majority.

“Tun Dr Mahathir spoke about Malays losing their grabs on power and losing their special rights and privileges due to the current political situation. [But] so long as the provisions in the Constitution remain, there is no issue of Malays losing their rights,” he said, pointing to how Article 153 is sufficient to protect Malays’ special position in the country.

Constitutional lawyer Kee Hui Yee agrees similarly that Article 153 is clear that the special position of the Malays and natives of Sabah and Sarawak are to be safeguarded in accordance with the provisions under the Article.

“This provision cannot be amended without the consent of the Conference of Rulers — hence, enough safeguard is in place,” Kee said, referring to Article 159(6).

Citing Professor Andrew Harding, a scholar in the fields of Asian legal studies and comparative constitutional law, Kee said that parts of the Constitution are unusual (or unique) in the sense that it sought to “advance the position of the majority” rather than to protect the minority — referring to the Malays.

“The justification for such special privileges is that historically, they are the economically disadvantaged groups.

“The Reid Commission accepted that special privileges should be given to the group but it did recommend that such special privileges be reviewed by the Parliament after 15 years (as stated in the report of the Constitutional Commission 1957),” Kee said.

Pointing to Article 8 and citing Harding, Kee said the Constitution is not a blank cheque that allows any kind of discrimination in favour of the Bumiputera.

“I do not think that [the Constitution] is pro-Malays as we must recognise that when the Constitution was drafted, a lot of compromises were taken into consideration. The provisions in the Constitution safeguard the interests of all races. Special privileges to Bumiputera, vernacular schools, citizenship, freedom of religion and etc,” Kee said.

On the other hand, Nik Ahmad Kamal suggested that Tun Dr Mahathir may be highlighting possible realities, that despite entrenched constitutional provisions, Malays’ rights and privileges could just be on paper only.

“That, I believe can become a reality if nothing is done to ensure the privileges mean something,” he said.

Dr Mahathir made his controversial remark as part of his attack against Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim’s administration, as he falsely accused the latter of being beholden to DAP in the Cabinet to turn Malaysia secular and without a religion of the federation.

The remark was also made after he was lambasted for playing the racial card ahead of the six state elections.

In response, deputy minister overseeing the law and institutional reform, Ramkarpal Singh clarified that the Constitution is not silent but recognises Malaysia as being multiracial, while Dr Mahathir’s claim that the Constitution never mentioned Malaysia as a multiracial country has no legal basis.

The Malaysian Bar also denounced Dr Mahathir’s statement as unacceptable and a mockery of the cherished principle of the rule of law, accusing it of serving no other purpose than to incite racial sentiments among the populace.