KUALA LUMPUR, May 8 — The refashioning of government-owned 1Malaysia Development Berhad’s (1MDB) financial dealings into a purported US$2.318 billion investment abroad was not economically beneficial at all, and it was only meant to give false comfort to 1MDB’s owner and board of directors that the company’s funds were still intact, a former Singapore banker told the High Court.

Kevin Michael Swampillai, a Malaysian who was a senior banker in the now-shuttered BSI Bank’s Singapore branch, believes the US$2.318 billion was intended to help 1MDB officials evade scrutiny from the auditors who were auditing the company’s accounts.

Swampillai said BSI bank officials even suspected that the 1MDB officials’ obsession with achieving the exact figure of US$2.318 billion of valuation for assets to back the “investment” sum, was because the company wanted to plug a hole or cover for losses by 1MDB.

But Swampillai also acknowledged that the bank had gave in to a threat from Low Taek Jho — who was portrayed to be then prime minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak’s advisor — to not dig further or ask too many questions about 1MDB transactions, as the bank wanted to avoid losing 1MDB which was a lucrative client.

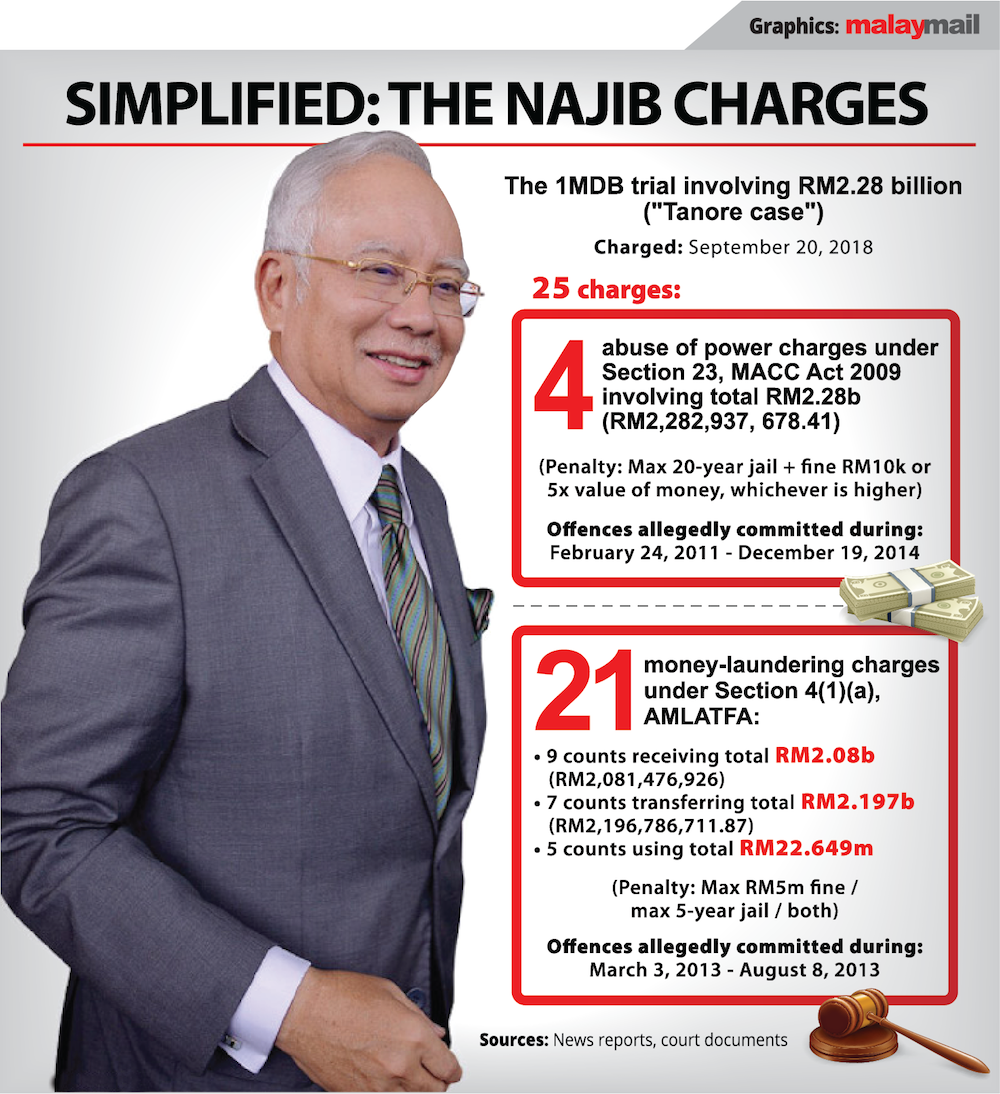

Swampillai said this while testifying as the 44th prosecution witness in Najib’s trial over the misappropriation of RM2.28 billion of 1MDB funds, which were alleged to have entered the former finance minister’s private bank accounts.

Was the US$2.318b fixation to cover up 1MDB’s losses?

The BSI bank was tasked to help carry out 1MDB’s Cayman Islands subsidiary Brazen Sky Limited’s US$2.318 billion investment via Hong Kong-based fund manager Bridge Partners International Investment Limited.

But for the 1MDB unit’s purported “investment”, Swampillai said 1MDB officials — who were also directors in Brazen Sky — were “very fixated” on the number US$2.318 billion and that they had kept bandying about that figure during discussions with the bank.

In order to justify the US$2.318 billion sum for the purported “investment”, 1MDB had to prove the value of assets — to support that US$2.318 billion figure —- in the form of two drill ships.

Swampillai said 1MDB officials even stated that they would prefer the two assets’ valuation to be stated as worth US$2.318 billion, but said 1MDB officials never gave any documents to show the price these ships were bought at and did not provide any valuation report which mentioned the ships to be valued at that exact figure.

“I as well as a few other people in BSI bank, my superiors also felt, we were wondering whether that US$2.318 billion figure that was being bandied about, whether it was to plug a hole in 1MDB’s balance sheet. So I remember that conversation taking place, so we suspected there were losses somewhere in the group,” he said.

A threat to stop prying

While BSI had asked 1MDB and Brazen Sky for information on the two drill ships, such information was not given and the bank had by now become very used to the lack of information from 1MDB, Swampillai said.

Swampillai said BSI’s Yak Yew Chee — who was the bank’s relationship manager handling clients like 1MDB — had helped convey a “threat” to the bank to back off from asking too many questions, as 1MDB might close down its accounts and stop giving its business to the bank.

Swampillai said Yak had conveyed the message and threat in an email to between 15 to 20 persons within the bank — right from the CEO, deputy CEO, compliance department, Swampillai himself and everyone involved in this 1MDB transaction, and said he believed the message came from Low or Jho Low due to the level of information that the bank requested.

Recalling that there was more than one email from Yak with such messages, Swampillai agreed with Najib’s lawyer Tan Sri Muhammad Shafee Abdullah that a number of individuals found it strange that Yak passed on the message as if he was not part of the bank but part of Jho Low’s outfit.

“I remember the emails vividly because it’s not always an employee of the bank would convey a threat issued by someone who’s not even a client of the bank, in that way, in that tone,” he said, adding that Low was personally also a client of BSI but he had no legal standing or connection to the 1MDB transactions.

Swampillai said the threat that BSI would lose all the revenue it had been getting from the 1MDB group of clients was a “powerful threat”, agreeing that the bank compiled to save its commercial interests and was willing to be wilfully blind to some obvious facts.

The last time that Swampillai had met with Yak was early this year in Singapore, and said he had the impression that Yak is living in China and returns to Singapore whenever required for questioning by Singapore or Malaysian authorities.

Zero benefits

The purported US$2.318 billion investment was from a “restructuring”, where 1MDB’s stake in a company would be acquired for US$2.318 billion, but with 1MDB not paid with cash but was only paid on paper with six “promissory notes”.

But Swampillai said there were many “red flags”, as the six purported promissory notes were a set of “IOUs” — usually referring to written promises to pay money owed to the other — that do not stand up to scrutiny.

Swampillai agreed that this US$2.318 billion purported investment had absolutely “no benefit” to 1MDB, and agreed with the benefit of hindsight that it was to carry out further fraud by evading auditors who were trying to find out the value of 1MDB’s purported assets in the form of the two ships.

The purported investment had no redeeming feature for 1MDB, with Swampillai saying this was a costly exercise for 1MDB: “I would also add it is very expensive to the company, it had no economic benefit but they had paid a lot in terms of fees.”

With hindsight, Swampillai believes the only reasons why the US$2.318 billion “investment” structure was carried out was to produce a false valuation report on the value of the two ships to avoid detection by the auditors, and to give the impression that these assets were no longer drill ships but converted into investments in six hedge funds — via the six promissory notes —- to give false comfort to 1MDB’s stakeholders and possibly to its board of directors that the money is secure in a credible fund.

Swampillai said 1MDB deputy chief financial officer Terence Geh had in late 2012 told him over the phone that 1MDB’s then auditor KPMG was “snooping around” these transactions and wanted to know the basis of the valuation for the US$2.318 billion investment in the Bridge Funds.

Previously, Swampillai testified that with the benefit of hindsight and with information made public in recent years, he believed Low intended to give the “optical illusion” — by using fiduciary funds such as Bridge Partners — that 1MDB funds were invested in genuine investments.

But Swampillai previously said that those “investments” were textbook or classic examples of sham transactions or fake investments, as the money which left 1MDB and was passed around different bank accounts of different companies would never make it back to 1MDB. He had also said the promissory notes were empty promises to 1MDB and that it looked as if 1MDB was giving away its money for free through its purported “investments”.

Najib’s 1MDB trial before judge Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah will resume tomorrow, with Shafee expected to continue cross-examining Swampillai.