KUALA LUMPUR, May 6 — The Federal Court last month decided to cancel the Kuala Lumpur City Hall’s (DBKL) approval to build apartment blocks on part of Taman Rimba Kiara’s land, ending residents’ nearly six-year-long battle to save and keep the entire public park intact.

Here’s how the Taman Tun Dr Ismail (TTDI) residents succeeded in stopping the apartment project by a private developer, and why the Federal Court found DBKL’s development approval to be wrong and illegal.

But first, what is this Taman Rimba Kiara case about?

In a nutshell, the case involved a park meant for public use and how half of its land was given out for a private project to build multiple apartment blocks, and whether DBKL had acted wrongly and illegally when approving the project.

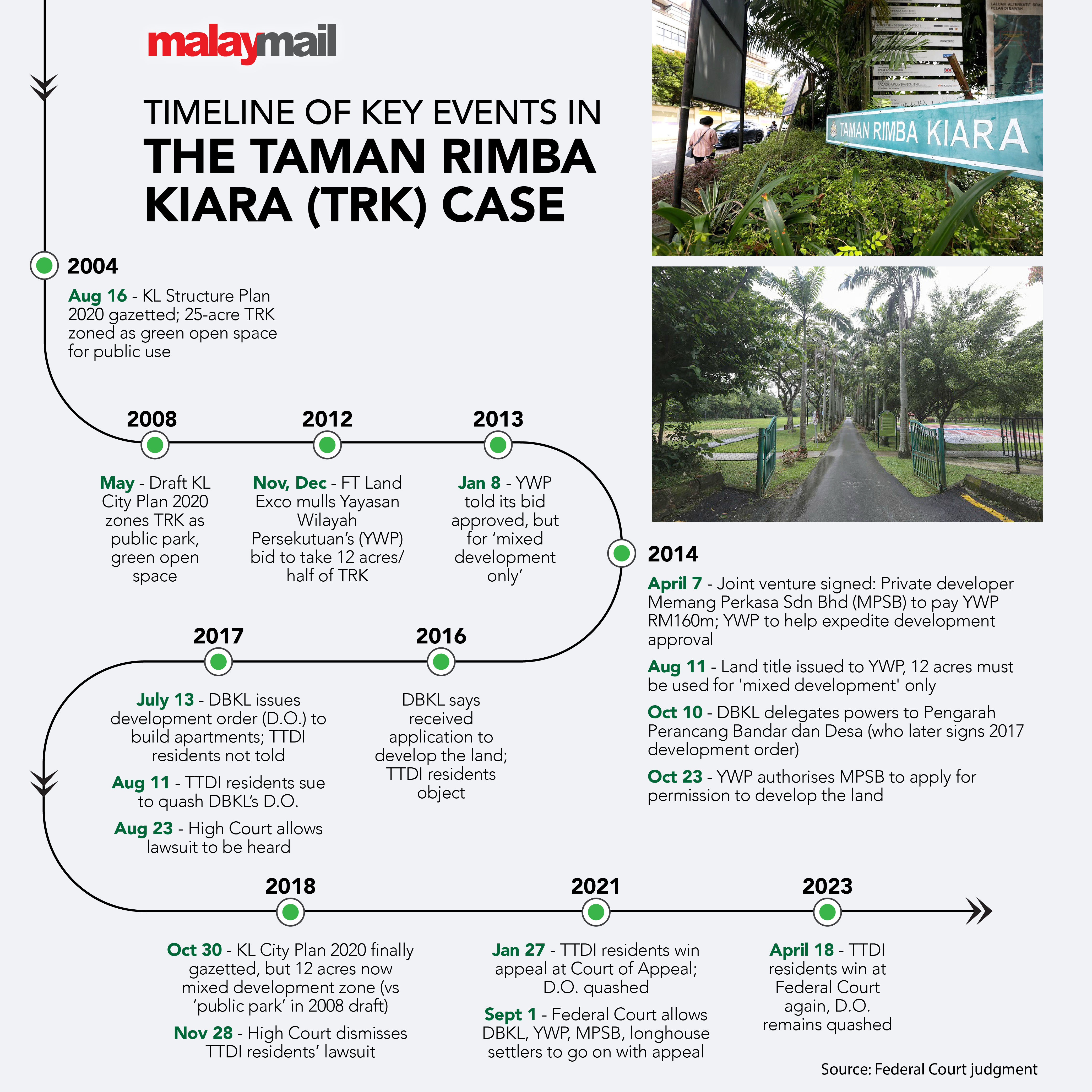

While the 25-acre Taman Rimba Kiara had previously been recognised as a green space for public use, the plot was broken up into two parcels in 2014, with half (12 acres) transferred to Yayasan Wilayah Persekutuan (YWP) for development.

Months before this transfer took place, however, YWP — which had the Kuala Lumpur mayor sitting on its board of trustees — entered into a joint venture with private developer Memang Perkasa Sdn Bhd (MPSB) to develop the same 12 acres.

In July 2017, DBKL issued a development order — without informing TTDI residents who had objected — to allow YWP and MPSB’s joint project to build apartments.

In August 2017, TTDI residents filed a lawsuit, seeking court orders to cancel the development order and to have DBKL adopt and gazette its city plan (which had recognised the 12-acre project site as a public park).

After losing at the High Court in 2018, the TTDI residents won at the Court of Appeal in 2021 and won yet again at the Federal Court on April 18 this year, which means that the apartment project must stop.

Jumping into the 290-page judgment

The Federal Court's unanimous decision to cancel DBKL’s development approval was made by a three-judge panel chaired by Chief Judge of Malaya Datuk Mohamad Zabidin Mohd Diah and composing of Federal Court judges Datuk Nallini Pathmanathan and Datuk Rhodzariah Bujang.

Here is Malay Mail’s summary of the key points in the 290-page Federal Court judgment written by judge Nallini, as well as facts from other court documents.

Two reasons on why DBKL’s development approval for half of Taman Rimba Kiara’s land was wrong and invalid:

KL mayor went against the law

The Federal Court said the mayor had wrongly and illegally exercised his discretion under the Federal Territory (Planning) Act of 1982 (FT Act), when DBKL ignored an existing master plan for Kuala Lumpur’s development (which marked the project site as a green space for public use) and approved the apartment project there.

There are two important development plans in this case: the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2020 that was gazetted in 2004 (which marked Taman Rimba Kiara as a green space for public use) and the more detailed Kuala Lumpur City Plan 2020.

The 2008 draft of the Kuala Lumpur City Plan 2020 still marked Taman Rimba Kiara as a public park and green open space, but the version which was finally gazetted in 2018 marked the project site (half of Taman Rimba Kiara) as a “mixed development” zone.

During the 10-year gap when the Kuala Lumpur City Plan 2020 had not been gazetted, many events happened: YWP came to own half of the Taman Rimba Kiara land, started a joint venture with the private developer, and the private developer had obtained approval from DBKL to start building apartments there, while TTDI residents had also sued to challenge the development nod.

Could DBKL — via the KL mayor — just ignore those development plans where Taman Rimba Kiara was zoned as a green space for public use, and go ahead to approve turning part of the land into a private residential space?

The FT Act’s Section 22 gives the KL mayor the power to exercise his discretion to either approve or reject applications for development approvals, even if his decisions do not comply with the development plans.

But the KL mayor does not have absolute powers to arbitrarily ignore development plans, as Section 22(4) imposes certain limits such as still requiring the mayor to consider the development plans as well as matters necessary for “proper planning”.

The Federal Court said the gazetted development plan KL Structure Plan (which zoned Taman Rimba Kiara as a green space for the public) “cannot be ignored or be shrugged off” and was a legally-binding document that DBKL must follow.

The court rejected the mayor’s argument that the KL Structure Plan was just a policy document that allegedly has no legal effect, saying the term “policy” cannot be used to bypass the need to comply with the FT Act.

The FT Act requires development in KL to be carried out according to the KL Structure Plan and KL City Plan.

The KL mayor tried to justify the apartment project’s approval, by insisting that DBKL could ignore the development plans meant for 2020 and could apply an older development plan — the Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) gazetted in 1967.

But the Federal Court said the CDP was an older and “outdated” map, which was only meant to be used in the transition period before new development plans for KL are developed and gazetted, and cannot be relied on to delay the gazetting of any development plans under the new FT Act.

The Federal Court pointed out that the newer KL Structure Plan was complete and the draft KL City Plan already prepared, and that both were part of the new structure plan system under the FT Act 1982, meaning it would be wrong to still rely on the 1967-era CDP in such a situation.

The Taman Rimba Kiara land is not even within the area covered by the CDP, and the mayor had no legal basis and was “fundamentally erroneous in law” to use the CDP to issue a development order for a development outside the CDP area, the court said.

Ultimately, the Federal Court concluded the KL mayor’s use of discretion to approve the apartment project was “fundamentally flawed” and illegal and invalid and “bad in law”, as he did not act within the limits of his powers under Section 22 and had gone against the purpose of the FT Act.

Saying that Section 22 was breached, the Federal Court said: “This in itself renders the exercise of discretion by the Datuk Bandar invalid and renders such exercise an illegality.”

This is one of the reasons why the Federal Court said the Court of Appeal was correct to quash the development order.

The KL mayor had conflict of interest

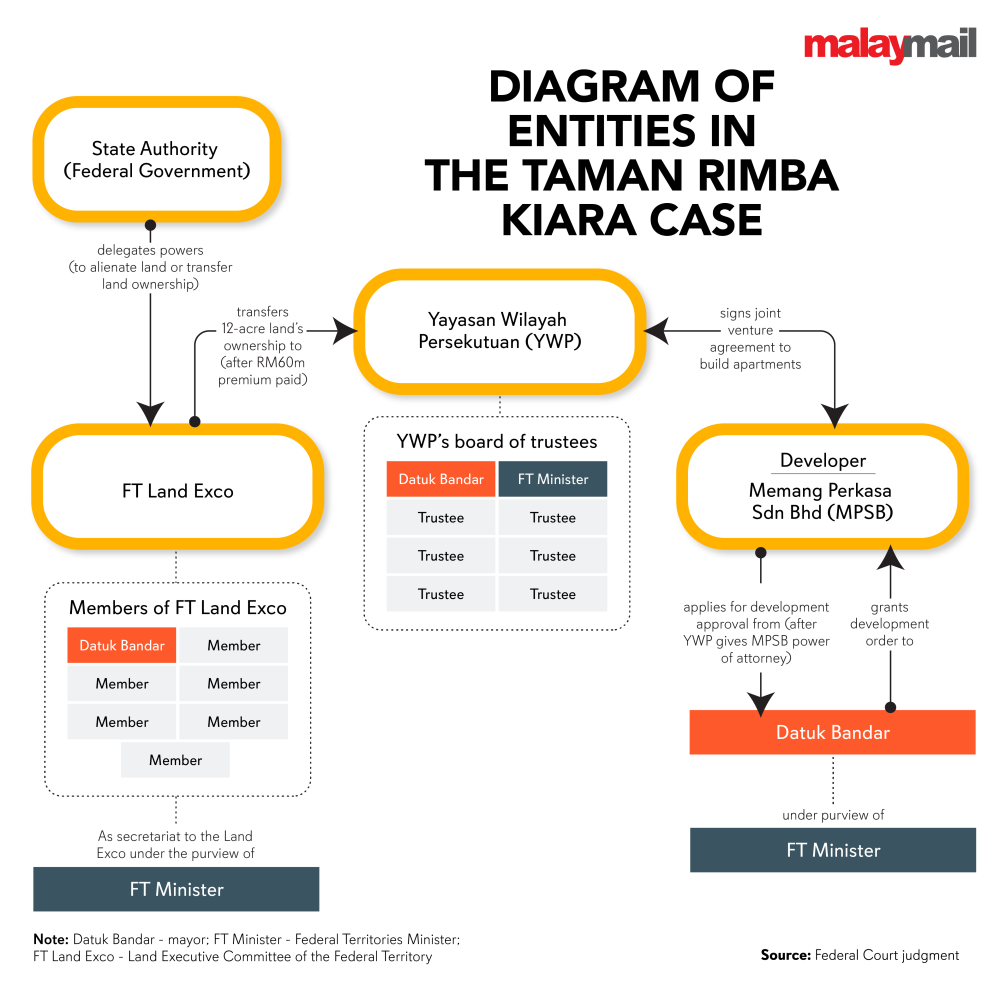

The Federal Court also decided that the KL mayor was not a disinterested party in the matter, due to the multiple roles he held, and that this point alone meant DBKL’s development approval was invalid and should be quashed.

“As we have concluded that there was a conflict of interest and/or bias afflicting the decision of the Datuk Bandar, which is a separate and independent ground of challenge, it follows that on this ground alone the Impugned Development Order is void and ought to be set aside,” the Federal Court said.

The Federal Court said the mayor was simultaneously a member of the authority that decided to alienate the land to YWP, a trustee of the project site’s new owner YWP that applied for development approval via its joint venture partner, and the institution with “complete control” to decide any development on the project site.

YWP was not only the landowner, but was also the applicant for permission from DBKL to develop the land (as YWP had given a power of attorney to authorise MPSB to apply for the development order on YWP’s behalf).

The mayor sat as a member of the Land Executive Committee of the Federal Territory (FT Land Exco) which had the power to decide to alienate the land to YWP and change the initial government land into private land that could be developed on.

Commenting on the KL mayor’s land exco role, the Federal Court said he should have been aware that the land was zoned as a green open space in the KL Structure Plan (gazetted in 2004) when the land was changed to a “mixed development” zone when it was alienated to YWP via a land title issued in August 2014.

Under an April 2014 joint venture agreement for “mixed development”, developer MPSB agreed to pay RM160 million to YWP with this amount dependent on a developer order being secured, while YWP was also required to assist MPSB for its applications with the aim of speeding up all approvals for development.

As a YWP trustee, the KL mayor would have been aware of the need to rezone half of Taman Rimba Kiara’s land for mixed development as the joint venture’s project was inconsistent with the existing land use under the KL Structure Plan.

As a YWP trustee, the mayor would also be aware the joint venture agreement would depend on the DBKL approving the development, and also be aware that YWP would have to pay over RM60 million to MPSB if the agreement is terminated or fails.

(By the time of the TTDI residents’ lawsuit, MPSB had already paid over RM66 million out of the RM160 million — over RM60 million as premium to the Land and Mines Office of Kuala Lumpur for the project site’s land — and RM6 million to YWP.)

The KL mayor did not personally sit in meetings to decide whether to approve the development application for YWP and MPSB’s joint venture project and did not personally sign the development order; he also delegated his duty to grant the development order to a planning committee and the development order was eventually signed by DBKL’s deputy director-general (planning).

But the Federal Court said the KL mayor as an institution still had conflict of interest when it approved the development.

The Federal Court focused on institutional conflict of interest instead of conflict in the mayor’s personal capacity, as the Federal Capital Act 1960’s Section 5 made clear that the “Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur” is an institution or body corporate, and that this meant the exercise of discretion to grant the development order was taken by the institution and not the person holding the office of the head of this institution.

Stressing it is the institution of the Datuk Bandar that approves any application for development, the Federal Court said: “The delegation and sitting out of meetings and the act of the Datuk Bandar himself not signing the Impugned Development Order does not cure institutional conflict.”

The Federal Court said DBKL did not exercise its discretion to grant the development order independently, fairly, or lawfully. Being in conflict of interest would taint DBKL’s granting of the development approval and make it unlawful.

DBKL should justify departures from KL Structure Plan to approve development

The Federal Court said DBKL did not tell objecting TTDI residents why it decided to approve development on half of Taman Rimba Kiara’s land at the time of its decision, nor did it give such explanations in this lawsuit.

Even without a law expressly saying so, the Federal Court said DBKL still has the legal duty to write to TTDI residents and explain its decision to deviate from the KL Structure Plan and to approve the development.

This was important as the TTDI residents were entitled to know why the development approval was justified, for transparency in DBKL’s decision, to ensure the legality of its actions, and to let those harmed decide if they wished to challenge DBKL’s decision in court.

The Federal Court said DBKL must clearly justify itself when there were legitimate objections to its development approval, and not only later in court when a lawsuit is filed against DBKL’s decision. (This is because DBKL’s defence of its decision in court documents is separate and different from its duty to explain to the public.)

Informing the public about the reasons for DBKL’s decision at the time of decision would enable the public to understand why the decision was made, instead of having to file lawsuits to find out the reasons.

DBKL has duty to make full and fair disclosure of all relevant facts to the court

As part of their duty of candour in lawsuits like the Taman Rimba Kiara case, public authorities like DBKL are expected to assist the court with “full and accurate explanations of all the facts relevant to the issue” to be decided and are also expected to disclose materials which the court would reasonably require to deliver an “accurate decision”, the Federal Court said.

Even with a clear allegation of conflict of interest against DBKL, the Federal Court said DBKL chose not to tell the court that the KL mayor — due to the National Land Code’s provisions — sits on the FT Land Exco (which decided to transfer ownership of the project site’s land from the government to YWP).

The Federal Court said it only discovered this during the court hearing when it asked questions, and when DBKL’s lawyer immediately confirmed the mayor’s Land Exco role.

“We concluded that the fact in issue, namely that the Datuk Bandar sat on the Land Exco which took the decision to alienate the land to Yayasan is relevant and significant, as this is a matter of public record, which ought to have been disclosed to the Court from the very outset,” the Federal Court said.

This fact of the mayor’s role in the Land Exco was important for the Federal Court to decide if DBKL had acted illegally and had a conflict of interest when approving the development.

Saying that DBKL had a public interest duty to disclose this important fact to the court, the Federal Court rejected arguments that it should not consider this fact for its decision, and said there should not be suppression, camouflaging or hiding of a “deliberate failure of disclosure.”

Just because an important fact was not disclosed to the court, the Federal Court said it could still decide on such facts — once it becomes aware of it — especially when it is related to possible breaches of any laws.

The Federal Court said the avoidance or suppression of this important fact would affect the court’s supervisory role to decide if DBKL had conflict of interest and if there were any illegalities.

The Federal Court said lawyers’ duty to their clients are subject to the lawyers’ overriding or primary duty to the court, as Malaysia’s adversarial court system depends on lawyers conducting themselves with “candour, courtesy and fairness” for justice to be achieved.

“Our adversarial system can only properly function to administer justice, if there is full disclosure by all parties in their capacity as officers of the court.

“If the court’s hands are tied to the selective and piecemeal extraction of facts and law, the result is an artificial advancement of our law based on the private interests of a select few at the expense of justice for all,” the Federal Court said.

DBKL can’t use government's broken promises to justify illegal acts

According to court documents, the Malaysian government had in the 1970s acquired the Bukit Kiara rubber estate, and had built 10 rows of longhouses on the Taman Rimba Kiara land for 100 families of the estate’s former workers to temporarily live in while promising to build them better housing there.

But since living there in 1980, the settlers are still waiting for the permanent housing promised to them decades ago. DBKL and the settlers described the longhouses as “dilapidated”.

In resettlement agreements signed during December 2015 to March 2017 between the settlers and the two joint venture partners, the developer MPSB agreed as part of its project to give 100 free units to them and to allocate another 100 units for their family members or nominees to buy at a preferential price of RM175,000.

The developer planned to build a 350-unit affordable apartment block (including those 200 units to be allocated to the settlers and their families) and eight blocks of serviced apartments on the land which DBKL approved to be developed.

DBKL had in court cited the resettlement agreement as one of its reasons for issuing the development order, and claimed that any delay in the development of the land would “delay” the settlers’ relocation to the apartments with modern facilities.

But the Federal Court panel said that DBKL’s failure to fulfil its decades-old promise does not justify the breaking of laws to enable housing to be allocated to the longhouse settlers.

The Federal Court said DBKL could not use the lack of providing of housing for the settlers to justify the granting of development order, as this development approval converts a public space for public use to a mixed development for private purposes and especially when this order goes against the FT Act.

The court said the issue of housing for the longhouse settlers is a “separate obligation owed” by DBKL to them, and the longhouse settlers should directly seek redress from DBKL instead.

The fact that the longhouse settlers have waited for decades and may continue to wait for new housing does not justify the development from going ahead, since there was violation of laws, the judges ruled.

Yes, TTDI residents can sue

One important issue was whether TTDI residents and the management bodies of TTDI residential buildings had the legal standing to sue, as it could either result in the KL mayor, YWP and the developer and one of the longhouse settlers’ groups winning their appeals, or enable TTDI residents’ lawsuit to be adjudicated.

The Federal Court decided that all 10 who filed the lawsuit had legal standing to do so, as they are “adversely affected” and their rights to use and enjoy the public park were encroached when half of Taman Rimba Kiara was converted for private development.

But even though the five management bodies of the Trellises Apartment, Kiara Green Townhouses, Residence Condominium, TTDI Plaza Condominium, The Greens Condominium had legal standing to sue, the Federal Court said they lacked capacity to file this lawsuit as they could not sue on behalf of every single owner and resident in their buildings.

Instead, these management bodies should have filed a representative action — otherwise known as a class action lawsuit — which is when several individuals have the same interest in a court proceeding.

But the Federal Court’s decision to quash DBKL’s development approval still stands, as the remaining five — TTDI residents’ association and four individual TTDI residents — do have legal standing and capacity to file this lawsuit.

What’s next?

On April 18, the Save Taman Rimba group, the Bukit Kiara longhouse settlers, the TTDI residents’ association said they want to work with YWP and the government to deliver “affordable, low density, permanent housing” for the settlers within the existing four acres where the longhouses are located, by using an alternative viable plan which does not destroy the adjacent green area in Taman Rimba Kiara.

As the Federal Court had invalidated the rezoning of Taman Rimba Kiara for development, the three groups urged for the new KL mayor and Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim (who oversees KL as the Federal Territories Department is now under the PM’s Office) to restore the land’s status as a “city park and public green space” in all current and future KL development plans including the KL City Plan 2020 and the KL Structure Plan 2040.

On April 30, Segambut MP Hannah Yeoh, whose constituency covers the Taman Rimba Kiara area and who had been supporting the Save Taman Rimba Kiara group’s court battle, urged the longhouse settlers to set aside their differences and have a common stand in order to push for new housing for them.

Yeoh also said she was looking to secure funding for the longhouse residents to help them when the process for their relocation starts.