KUALA LUMPUR, April 26 — Australia’s investigators had decades ago highlighted Sabah’s “Double Six” Tragedy — where then Sabah chief minister Tun Fuad Stephens and all 10 others onboard died in a June 6, 1976 plane crash — was an “accident bound to happen sooner or later”, a newly-revealed report said.

The Australian investigators’ 1976 report said it was possible to discount or rule out the theory of sabotage in the first few days of a Malaysia-led investigation in 1976 on the crash, and pointed to an earlier preliminary investigation which found overloading at the back of the aircraft to be the cause.

The Australian investigators’ report numbers 11 pages and was part of the 52-page record declassified by the Australian government today.

In the report, Australia’s investigators highlighted multiple points seen as relevant to the crash, including the airline Sabah Air’s alleged “illegal” and “poor” operations, as well as shortcomings and poor flying abilities by the pilot of the Nomad N22B aircraft which crashed.

The Australian-owned company Government Aircraft Factories (GAF) manufactured the Nomad aircraft which crashed in 1976, and had sent its acting chief designer David Hooper and chief test pilot Stuart Pearce to Malaysia to assist in Malaysia’s own investigation on the crash.

In the report signed by Hooper and Pearce on the findings of GAF’s separate investigation on the crash, they said the relevant information included Malaysia’s Civil Aviation Department (CAD) failing to completely fulfil its obligations as the local certifying authority.

The report said the CAD had never approved Sabah Air’s draft Operations Manual and that means the airline was operating illegally, and said the draft document contained inaccuracies on aircraft operation and with deviations from the flight manual to the extent optimum performance would not be achieved during flight operations.

In the same report by the GAF investigation team on the 1976 crash, it claimed the pilot Captain Ghandi Nathan to have “sub-standard ability” and several shortcomings in his personal file with Sabah Air, despite his experience being some 3,000 flying hours.

According to the GAF report, the pilot Ghandi was reported to have poor ability to deal with simulated emergencies, and that Sabah Air’s previous chief pilot M. Nadan had after flight checks on Ghandi repeatedly reported the pilot as having “substandard ability with emergencies, instrument flying” and operating single-engine aircrafts and recommended further training.

The GAF report also cited interviews with one of the two remaining Sabah Air pilots, where this pilot named Captain Cameron said that the airline’s pilots never bothered to physically calculate the loading of baggage onto an aircraft before take-off, and that they would simply eyeball the baggage’s location and take off if it looked satisfactory.

This pilot had also said they did not use the loading charts in the flight manual as they were too difficult to understand.

Sabotage ruled out

Earlier, in the GAF report, the Australian company’s investigators said sabotage was high on the list of theories considered by investigators as a cause of the 1976 accident.

“It was possible by various means during the first few days to discount this theory,” the GAF report said, noting that the CAD’s R. Williams’ “thorough and painstaking examination of the wreckage revealed no evidence of any pre-crash malfunction or failure of any complement or structure which would cause the aircraft to crash”.

The GAF report added that it was concluded that there was overloading in the rear baggage locker of the aircraft.

What happened before the crash?

In outlining the chronology of events before the “Double Six” crash, the GAF report said the Nomad aircraft had been on two earlier flights between Labuan and Kota Kinabalu on that day, and that there were no reported aircraft issues which required attention by maintenance engineers and that the flight appeared normal.

On the third flight which was the one which the plane crashed, Captain Ghandi supervised the loading of baggage in the front compartment, while a co-pilot — who was later bumped off the flight — supervised the loading of baggage into the rear locker.

“None of the baggage and freight was weighed prior to placement in the aircraft and the driver of the vehicle which brought the baggage to the aircraft reported that the rear locker was about three quarters full,” the GAF report said.

Captain Ghandi was also said to have told his acquaintances on that day that he was tired and unwell, due to what he believed to be tainted food he had ate the previous night.

He was also said to have sat in the pilot’s seat when the 10 passengers were boarding and that he did not supervise the loading of the passengers onto the plane.

In giving the likely crash sequence where the plane went into a spin and nose-dived into the sea after being given clearance for landing at Kota Kinabalu, the GAF report gave technical details on what investigators believed happened, including how the pilot may have lost control of the aircraft when landing due to overloading at the rear.

“In view of Ghandi’s reported difficulties with aircraft emergencies, his sub-standard flying ability and his self-confessed illness, it is doubtful if he realised what the problems were and in losing control of the aircraft was unable to appreciate the situation sufficiently in order to regain control,” the GAF report said.

The GAF report also said that its investigators had sighted the contents of a preliminary investigation report in 1976, where it was stated that “the cause of the accident was that the pilot had allowed the aircraft to be loaded well beyond its aft CG limit and as a result of this, he lost control and crashed during the final approach to land”.

The aft CG limit is a reference to the rear of the aircraft loaded beyond its limit, which affected its centre of gravity or its stability and balance.

The preliminary report was said to be presented at a Malaysian Cabinet meeting on June 16, 1976, with the Malaysian government then declining to issue a press release but agreeing that the GAF “could advise its customers and operators that as a result of the investigation, the structural integrity of the aircraft was assured”.

The GAF report said Australian personnel were not authorised to make public any of the findings of Malaysia’s investigation and that the Malaysian government had called for a complete report by June 30, 1976 where it would presumably make the findings known. But the GAF report said it was not confident that the full Malaysian report would be published in this timescale.

GAF says not aircraft’s fault

In the 11-page GAF report marked as “Company Confidential” but now declassified, the two GAF investigators said they believe their detailed knowledge of the Nomad aircraft enabled them to help the Malaysia-led investigation team in the probe and to expedite a series of logical conclusions, particularly on failures in the flying control systems found when examining the wreckage, loading calculations, operational and handling considerations.

“During the discussions of likely causes and findings, a number of uninformed comments were made. We believe that had the GAF personnel not been present to correct inaccuracies, the investigation may well have concluded in a different light, possibly with criticism being levelled at the aircraft,” the report by the Nomad aircraft’s manufacturer GAF said.

The GAF investigators also said the Australian company’s investigation team on the Sabah crash should not be too closely associated with Australia’s Department of Transport, as the department had attempted to be seen as impartial by making comments during the investigation “which were perhaps seen by others to imply criticism of the Australian product”.

In making recommendations in the GAF report which was distributed internally among 13 individuals including key company officials, the GAF investigators said it was “problematical whether in fact diplomatic representations are really necessary since it is normal international practice for the manufacturer’s accredited representatives to be available to investigation teams in all serious aircraft accidents”.

The GAF report also recommended that the factory issue press releases at the earliest opportunity during such investigations in order to minimise “rumours and false statements”.

In the same 52-page record, the GAF’s manager J.H Dolphin signed on June 21, 1976 an internal communication to GAF members, which said GAF had two concerns, where it was shocked with the tragic loss of life in the Nomad crash in Sabah, and that “secondly, there was fear that the crash and therefore the tragedy could have been due to a failure of the aircraft”.

While saying that GAF and the DOT cannot make any statements and will have to await Malaysia’s official announcement on the investigation’s findings, Dolphin had said: “Nevertheless I am very aware of the second matter of concern mentioned above, and in that respect, I believe we can cease worrying.”

The GAF manager did not elaborate further why GAF could stop worrying that any aircraft failures could have caused the crash, but only expressed hope that Malaysia would announce its findings in the near future.

Sabah’s former chief minister Tan Sri Harris Salleh recently reached an agreement with the Australian government when seeking for the National Archives of Australia’s (NAA) full release of Australia’s records on its own investigation on the Double Six crash. These were Australia’s 52-page record dubbed B5335 and a separate cache of documents dubbed B638 (136-page Part 1 and 20-page Part 2).

Following the settlement between Harris and the NAA, Australia’s Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) on April 24 allowed full access to the documents.

Harris’s lawyer Jordan Kong confirmed to Malay Mail today that the law firm Jayasuriya Kah & Co which was acting for Harris had received the Australian investigation report (B5335 and B638) this morning, and that Harris had asked for the reports to be made available to the media and the public.

The 52-page record which contains Australia’s investigation report by the GAF investigators can be found here.

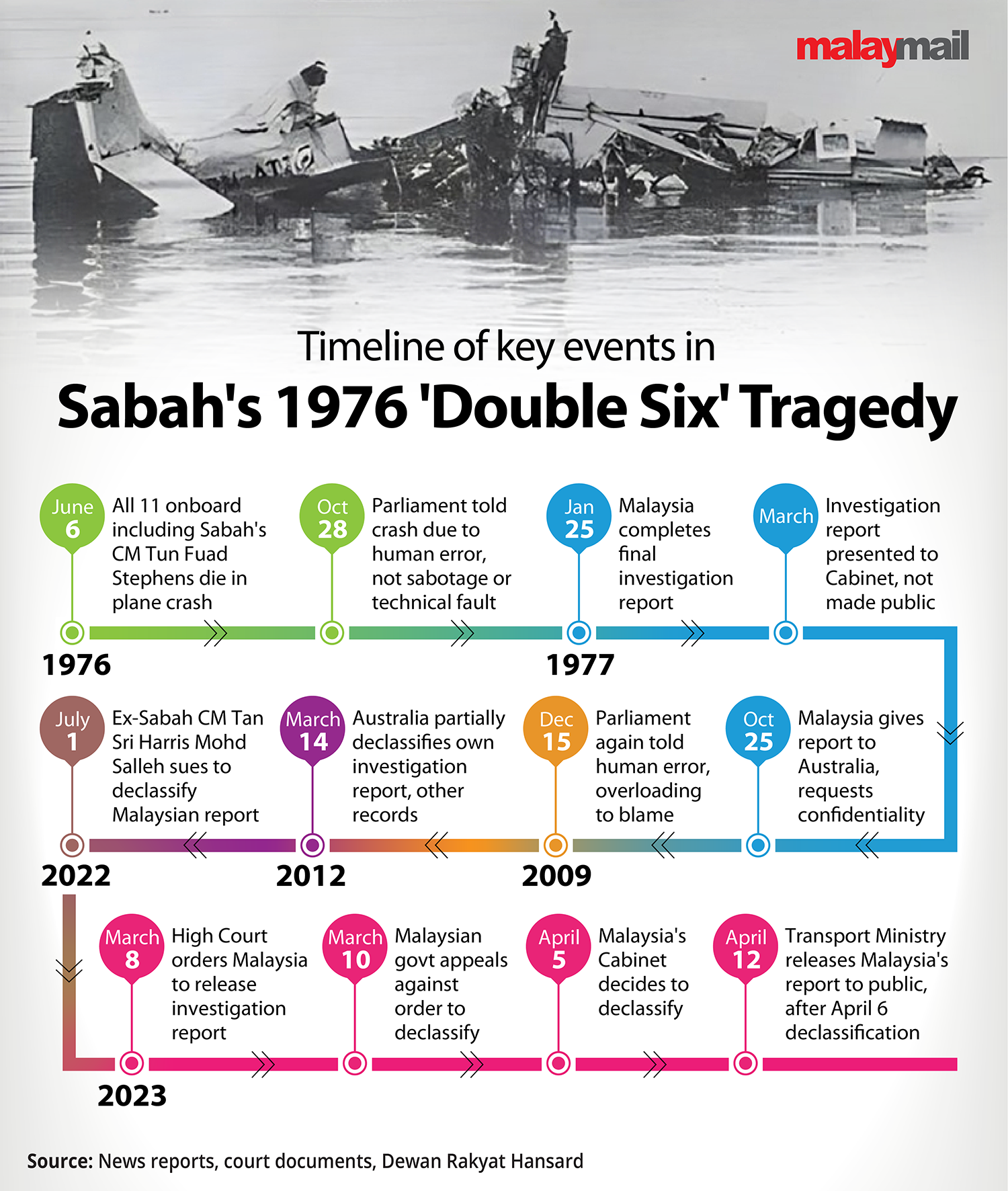

Read here for Malay Mail’s summary of events which led to Malaysia’s declassification of its own investigation report.