KUALA LUMPUR, April 17 — Former Singapore-based banker Kevin Michael Swampillai today said he had a “sinking feeling” that something had went wrong with 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), which was a client of the BSI bank where he worked, amid news reports that 1MDB funds had ended up being spent on a yacht, private jets and properties.

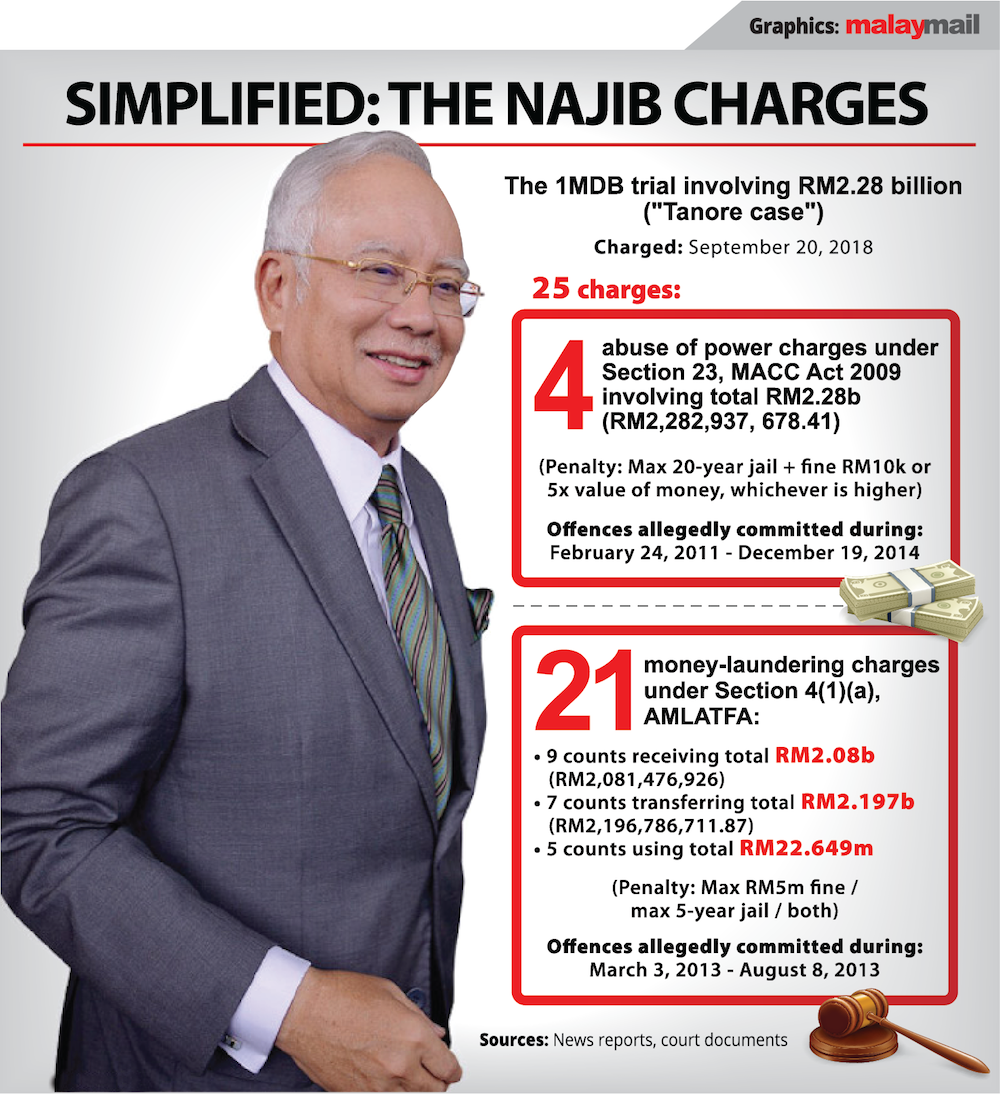

Swampillai said this while testifying as the 44th prosecution witness in former prime minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak’s trial over the misappropriation of RM2.28 billion of 1MDB funds, which were alleged to have entered the former finance minister’s private bank accounts.

Even from the very start when 1MDB and its related companies opened accounts at BSI Bank, Swampillai said there were already multiple “red flags” about 1MDB.

But Swampillai said BSI Bank, which earned more than US$250 million (RM1.1 billion) in fees from the “lucrative” client — 1MDB and its group of companies — eventually stopped asking questions about the red flags and problematic issues, such as now-fugitive Low Taek Jho’s influence over the companies despite lack of documents proving his alleged role as 1MDB adviser.

Swampillai said there was a lot of speculation among BSI bankers over where the huge sums of funds that went out from 1MDB and SRC International Sdn Bhd would eventually end up after being placed in “fiduciary funds” through BSI bank for purported investments, and when the funds would return from those “investments” via the fiduciary funds.

“If the money does not come back, you are going to create a huge hole in the balance sheets. The concern was whatever they were doing with those monies, we were certainly hoping they were investing. To a large extent, we also wanted to believe what Jho Low told us, government-to-government, which seems to indicate bona fide investment, hoping that was the case. If it wasn’t the case, clearly it would be a huge problem down the road.

“At the end, we didn’t know where these monies ended up, or when would this money be coming back. Towards the end, as news started coming out in the media, these huge fund flows, these fiduciary fund structures, that’s when it began to dawn on us — not everybody on the government side, Malaysian side knew what was actually happening with these transactions.

“I think that’s when in the bank we started to develop a sinking feeling that something has gone wrong, these monies had probably ended up in someone else’s pockets. That was the concern and that’s what came to pass at the end of the day,” the Malaysian ex-banker told the High Court when cross-examined today.

Asked by Najib’s lead defence lawyer Tan Sri Muhammad Shafee Abdullah if he now knows with hindsight that those purported “investments” were never meant to come back, Swampillai replied: “In terms of what’s come to light, what these monies ended up in, yacht, private jets, real estate, these monies were never intended to come back.”

Swampillai today said he believed that the fiduciary funds — which could actually be used for legitimate reasons — were “misused” to give the illusion that the money belonging to 1MDB and its group of companies were put in genuine investments.

It was in early 2015 that he realised the attempt to give the illusion that 1MDB funds were being properly invested, due to reporting on blogs and Sarawak Report, which started in 2013 and which increased in crescendo in 2014 and 2015, until mainstream media such as the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times started to also report the matter in 2015.

In hindsight, he now believes that the fiduciary funds were misused to carry out money-laundering involving 1MDB and its related companies, with the intention of obscuring or hiding the identity of the “ultimate beneficiary” of the money.

Declining to comment on BSI Bank’s relationship manager Yak Yew Chee, who brought in Low himself, 1MDB and SRC to become BSI clients, the former banker Swampillai, however, said he and other bankers within the bank did not know that money laundering was actually going on.

“I cannot attest to what Yak Yew Chee knew and the kind of conversations he had with Jho Low with regards to these transactions, because he had a very close relationship, he was the relationship manager, he liaised very extensively, very intimately with Jho Low, so I can’t speak to his knowledge.

“But I can speak to my knowledge and the rest of the bank, we had no knowledge of how these funds were being used. So in that sense, I will say with all honesty, we did not assist in money laundering, because we didn’t know it was money laundering at the material time,” he said, having said he did not know the 1MDB group of clients’ intentions and where their money was intended to finally end up.

Swampillai said the stern warning he had received from Singapore’s authorities and the charges that were pressed against his BSI Bank colleagues in relation to 1MDB were all not related to money laundering, which he said indicates that Singapore has no evidence that the bank and its employees were aware of the “true nature” of those transactions then.

Swampillai said he had a “prevailing sense” that something “dodgy” was going on in relation to 1MDB and that there were always suspicions about the 1MDB-linked transactions, but there was no information available to enable a conclusion about those funds.

As early as 2011 when SRC opened its account with BSI, there were already “obvious red flags and gaps in due diligence” as BSI Bank continued to pose questions for compliance purposes over a period of time, but the information was not being provided by SRC to the bank.

Swampilllai listed the red flags as including 1MDB and its related companies being in the category of “politically-exposed persons” and government entities which would typically go to investment banks or commercial banks if they intended to open accounts for investments, instead of the “relatively small and obscure private bank” BSI, as private banks would tend to handle high-net worth individuals as clients instead.

He also listed the other red flags as being large transactions being approved by single signatories without board minutes, the use of fiduciary fund structures, and transactions for purported investments being backed up by promissory notes documents which had no economic value.

On Low’s decision to choose BSI to carry out these transactions, Swampillai said: “With the benefit of hindsight, it was probably a masterstroke on his part. I think he correctly deduced by going to a smaller private bank, it would be easier to get accounts opened and undertake those transactions undertaken in those accounts, namely the use of fiduciary funds to make obscured or shielded transactions in the way that they did.”

Believing that a bigger bank would have very early on stopped the 1MDB transactions which had many red flags, he believes BSI Bank did not file any suspicious transaction reports (STR) to Singapore’s authorities, but suggested it was possible that the bank had filed such STRs towards the end when it was already too late to prevent the transactions.

He said an STR would typically be a “prelude” to the closure of a bank account, where the bank would have already decided it would terminate the client and report the client to authorities and also indicate a willingness to cooperate with authorities by providing information on the client and their transactions through the account.

If an STR was filed early on, it would mean the account and transactions would have been stopped, he said.

When concerns about 1MDB transactions were raised to higher-ups in the bank, he said a meeting would typically be called where the concern would be discussed but nothing would happen and that he would not know what the senior management decided, saying: “The very fact that the transaction is authorised, that sends signal down the line, the senior management is comfortable with these transactions and the subliminal message is full steam ahead, get it done.”

“In the early days, the bank used to pound the table and asked about board authorisation, who is Jho Low, and what is his connection to this account. But at some point, BSI Bank stopped asking those questions, and particularly after the bank was threatened by Jho Low that you know, no further questions would be entertained,” he said.

He believed BSI decided it needed the money from having 1MDB as a client possibly after doing a cost-benefit analysis and that the bank became wilfully blind by not continuing to ask further questions about Low’s role in 1MDB, after Low threatened to close down and move the 1MDB bank accounts.

Swampillai said the over US$250 million in fees which BSI earned from the 1MDB group of clients meant that it was the “most lucrative client” and “single largest client” for the bank in terms of transaction volumes and revenue and that it contributed to about 10 per cent of BSI’s total revenue, and said the bank also earned quite significant revenue from Low and his family members, who also had bank accounts with BSI.

Swampillai said Yak — who brought in 1MDB, SRC, the fake Aabar Investment PJS Limited and Low as customers for BSI — became the highest-paid banker in BSI globally and was paid even more than BSI’s chairman. This was due to Yak having negotiated to get a percentage of revenue generated by the 1MDB group to BSI to be paid to him in the form of yearly bonuses.

Najib’s 1MDB trial before judge Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah resumes tomorrow, with Shafee expected to continue cross-examining Swampillai.