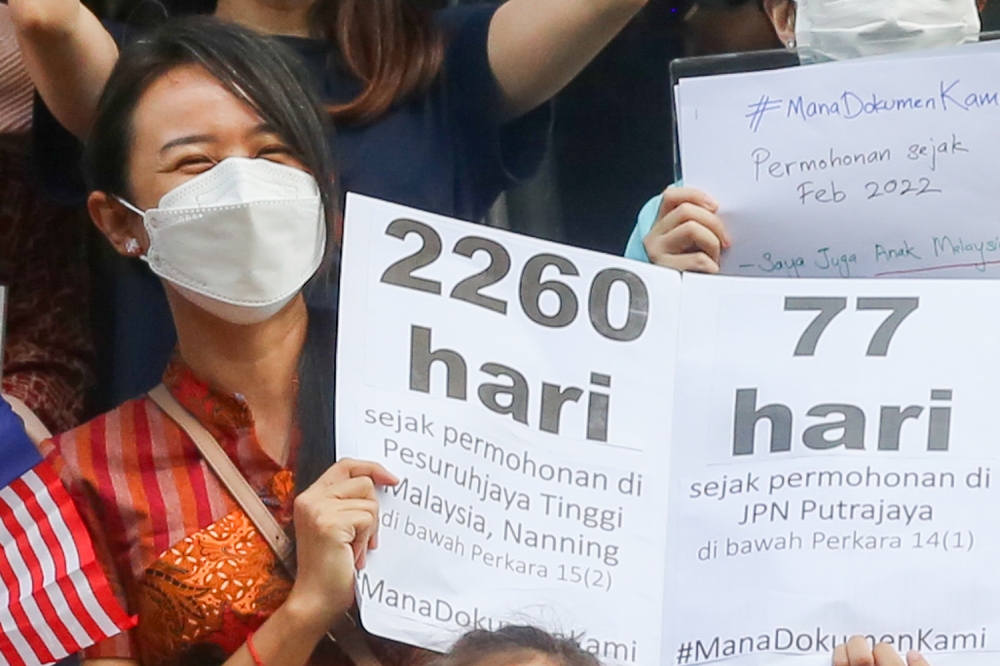

KUALA LUMPUR, March 16 — For many Malaysian children aged seven and above, the start of the new school year from March 19 in the Covid-19 era is a chance to make new friends or reconnect with old ones.

But for the overseas-born children (OBC) of Malaysian mothers living here, such joy as they might feel will have to be delayed to April or even later, depending on whether or not the public schools have any more space left over.

Selangor-based mother Alison Wee’s daughter is one such example. The girl was born in China seven years ago and should be starting Standard One this month, but her entry into the Malaysian public school system is being held up due to extensive paperwork.

“Right now, she should be entering primary school. If she’s a citizen, she will follow the other Malaysian kids and enter school by March 20,” Wee told Malay Mail in a recent interview.

She related how she went to the Consulate-General of Malaysia in Nanning, China to apply for her daughter to be a Malaysian citizen in 2016. Till today, Wee said her daughter’s citizenship application is still being processed.

Now that the daughter is seven this year, Wee has to obtain a student visa for her. The student visa is important as it is the document that will allow overseas-born children aged above seven to continue living with their Malaysian mothers and relatives in Malaysia.

“Since then, she has been here, she has not been back in China since the pandemic. She has been attending kindergarten here, learning Negaraku, singing that every week, every Monday,” Wee said, adding that she and her daughter have been in Malaysia since the child has been four.

What OBC have to do to attend public schools

The bureaucratic process for non-citizen OBC to attend local public schools is not only daunting but tricky.

For mothers in Selangor like Wee, it starts with sending an application form — for the enrolment of non-citizen students into government schools or government-aided schools — along with three sets of documents (such as birth certificates, passports, marriage certificates) to the state Education Department.

After that first step, applicants wait for the approval letter to attend public schools. Once they have that, they need to go to the district education office to pay an annual fee and obtain another letter addressed to the Immigration Department that states the school the child will be attending. And then they have to go to the school to obtain a verification letter addressed to the Immigration Department.

After obtaining those letters from the district education office and the school, they will need to go to the Immigration Department to present those letters, a receipt of the fee paid, a letter from the National Registration Department and a passport — in order to obtain a student pass or student visa.

After that, they will then need to go back to the district education office to again get a letter on which school they will be placed in — this time the letter is for the school — and finally report themselves to the school to register the child as a student. That is when the OBC can finally start school.

Wee sent her daughter’s enrolment application to the Selangor Education Department on September 12 last year. To date, she has yet to receive the approval letter.

“I think this is very unfair for mothers in my situation and for the children. Even if she enters school now, she has to repeat the same process every year, apply for a student visa again, run around for papers again. Every year, the student will have to miss school.

“For a working parent, it’s very taxing on us. Every time we have to run around for paperwork, we have to take leave from work.

“I hope that the government can be more lenient with this. If let’s say the non-citizen child has a Malaysian mother, then it is logical or reasonable to try to place the child in school as soon as possible. I think we should not be treated like complete foreigners in our own country,” said Wee, whose Dutch husband is currently working in Brunei.

Why public schools?

The 39-year-old university lecturer finds it ironic that she dedicates herself to teaching the next generation but faces so much difficulty in ensuring education for her own child.

While there are more schooling options in Malaysia now like international institutions or private schools which would have an easier enrolment process, Wee pointed out that not every parent can afford them.

A product of the Malaysian public education system, she said local schools have a bigger student population and believes this provides her daughter the chance to mingle and make friends with people of diverse backgrounds.

“For myself, I really want my daughter to go through our public school system. I have confidence in our public schools. I think it’s great. I myself went through the public school system all the way up to STPM, I really hope my daughter gets the same experience, it’s just that we can’t enrol in time,” she said.

Enrolling OBC with special needs

Kuala Lumpur-based housewife Nuraini Ahmad has two special needs children, a nine-year-old son with intellectual development delays and a seven-year-old autistic daughter.

The boy has Malaysian citizenship as he was born in Malaysia. He also has an “OKU” card issued by the Social Welfare Department for Malaysians with disabilities, which enables him to receive free medical treatment, admissions and therapy at government hospitals for free.

His OKU card also enables him to attend special education classes in the local public school and entitles him to RM150 allowance.

His sister does not have an OKU card as she was born in Saudi Arabia and her citizenship application filed in Riyadh in 2017 was rejected without any reason given.

To put her in a local public school with special education classes, Nuraini had to first obtain an evaluation letter from a government hospital specialist, to be shown to the district education office.

And just like in Wee’s case, Nuraini will have to pay school fees and buy textbooks for the girl, all because she is a non-citizen at this point, and apply for an annual student pass.

“She has to apply each year to the school, renew her student visa each year. My first child, I don’t have to think much, no need to renew, just go to school and change classes only,” the 43-year-old mother said, highlighting the different treatment for her two disabled children based solely on their citizenship status.

In addition to the evaluation letter, Nuraini must secure an insurance policy for her daughter, which is one of the Immigration Department’s conditions for student visas to be issued to non-citizen children.

“It’s a bit difficult for an autistic child to get medical insurance as most of the insurance companies I enquired with said they don’t cover special children, autistic children,” she said, adding that she had even paid for an insurance policy only to have it rejected due to her daughter being autistic.

“From last year, I have been stressed when I think of enrolling my daughter into school, I couldn’t sleep at night and kept thinking about insurance. How to get into school if insurance is needed, if we don’t apply for student visa, she cannot stay in Malaysia, if she has to leave Malaysia, I also have to leave Malaysia,” Nuraini told Malay Mail.

Thankfully, she was finally able to obtain an insurance policy for her daughter. But there are other hurdles to jump to enrol her non-citizen daughter into Nuraini’s preferred school, which, for practical reasons, is the same one as her son attends.

“Another thing, for the non-citizen child, she will enter school late. Children with Malaysian citizenship will enter on March 20, but our child will enter two weeks late, so only in early April, my child can enter. Late because they give priority to children with citizenship, and after that when there are empty slots they enter our children to school,” she said, noting that she would only be notified on March 29 on which school her daughter will be placed in and that the child will lag behind in her class.

Nuraini hopes that the government will quickly resolve the citizenship issue for OBC by amending the Federal Constitution.

“Mothers are stressed. If possible, we want to have this solved quickly because we have been struggling for years in facing the same issue — bureaucracy, financial problems, and family problems.

“I ask for the government to speed up this amendment because we have been forced to face government bureaucracy for too long. If possible, I hope next year there will be no need to apply for a student visa. I hope my child can go to school easily.”

Followed all instructions, but schooling still delayed

A Johor single mother who only wanted to be known as Ma has been jumping through hoops to get Malaysian citizenship for her China-born daughter even before the girl was born.

The 38-year-old told Malay Mail that it started with the “wrong” information given by a National Registration Department (NRD) officer in her Johor hometown.

According to Ma, she was told she could apply for her daughter’s Malaysian citizenship even if the latter were born in China, and that dual citizenship would be allowed until the child turns 18.

After an earlier failed bid in 2016, Ma's second citizenship application in late 2017 for her daughter is still being processed.

Fearful to leave her daughter’s education to chance, Ma contacted a local school principal last July about the enrolment process and was told she can apply only in October as Malaysian students were prioritised for entry.

And so she did. The process went smoothly at first. Ma obtained the Education Ministry’s approval letter for her daughter to obtain a student pass from the Immigration authorities in just a month last November.

But Ma said the Education Ministry told her non-citizen children could only start applying to Immigration in January as the new school year now starts in March.

On January 6, she submitted all the necessary documents to the Johor Immigration department. Four weeks later, Ma was told that the application had been approved, but that she needed to go to Putrajaya to cancel her daughter’s long-term social pass since it was issued there, and exchange it for a student pass.

On February 23, she went to Putrajaya to get it done and was issued a special one-month pass for her daughter.

On March 3, she returned to the Immigration office in Johor Baru to apply for the student pass, only to be told that it could not be issued as the daughter’s special pass is still valid and as she could not hold two passes at the same time.

Ma said she was told by Immigration officials in Johor that she would have to wait three days before the special pass expires before she can exchange it for a student pass.

This meant that Ma’s daughter would only get her student pass on March 27 at the earliest, after taking into account certain work holidays around that time, which would delay her daughter’s schooling.

Her daughter’s school starts on March 19, but the lack of the student pass means she cannot show up in school yet — even though the school has already kept a seat for her.

“So I’m really upset, I did it very early, but in the end, my daughter still cannot start school in time,” the mother of one vented.

“My only hope, and my daughter’s hope also, after waiting for so long, we want citizenship only,” she said.

Ma said she could see tyat the current government has started taking steps to address the citizenship woes faced by Malaysian mothers with OBC and hopes it can be speeded up “so we don’t need to run to so many states and steps, it’s so difficult for us”.

She added that for the past seven years, she had to travel all over Johor as well as to Putrajaya with her daughter to deal with the paperwork to renew the long-term social pass.

The long-term social pass is required for non-citizen children aged below seven to stay in Malaysia, while those aged above seven have to switch to getting a student pass.

Beyond the delay in enrolling their OBC in public schools, the mothers Malay Mail spoke to said there were many other challenges. Their non-citizen children are not entitled to free medical care including dental check-ups and vaccination shots.

Non-citizen OBC also cannot represent their schools in competitions or at higher levels such as the state, “no matter how outstanding” they are, simply because they do not have Malaysian citizenship, Wee said.