KUALA LUMPUR, March 2 — Former BSI Singapore banker Kevin Michael Swampillai said he and other colleagues had raised their suspicions about 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) and related companies like SRC International Sdn Bhd to the higher-ups within the bank, but said they were instead encouraged to continue carrying out the lucrative transactions involving huge sums of money.

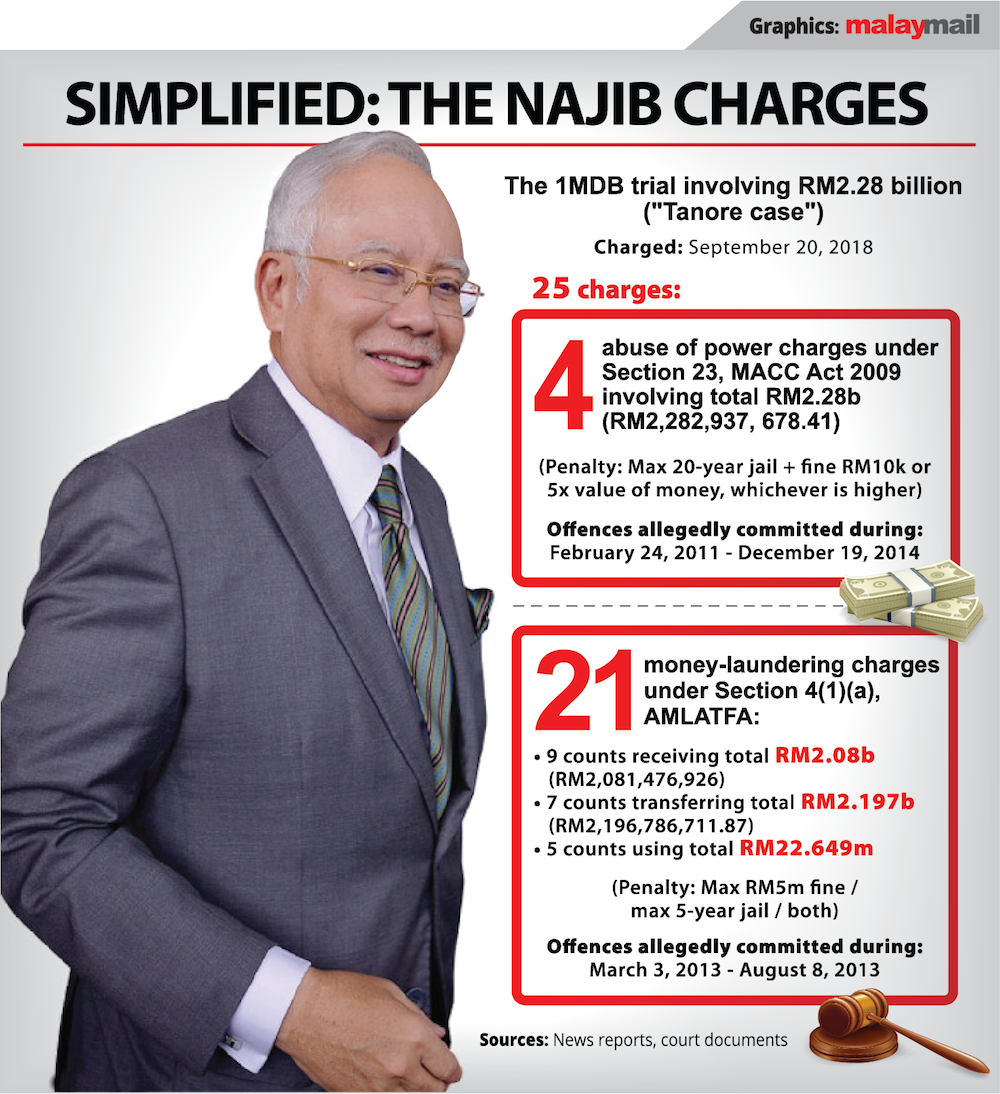

Swampillai was testifying as the 44th prosecution witness in Datuk Seri Najib Razak’s trial, where the former prime minister is accused of having received RM2.28 billion of money originating or belonging to 1MDB into his private bank accounts.

Questioned by Najib’s lead defence lawyer Tan Sri Muhammad Shafee Abdullah, Swampillai confirmed that he felt it was odd that these Malaysian government-linked entities or sovereign wealth funds had chosen BSI Bank which was not even a large bank and confirmed the monies transacted were huge sums.

“Yes, I did have suspicions. I did have concerns at the very beginning during the SRC phase of these transactions, I voiced my concerns, not just SRC, but even Brazen Sky transactions, I voiced my concerns to my supervisors in the bank. I don’t think I was the only one for that matter, I believe there were loads of concerns being expressed by compliance in particular,” he told the High Court.

“I raised my concerns in the beginning but I think it sort of fell on deaf ears within the higher echelons of the bank because nothing was being done to stop these transactions.

“But there was no factual basis for these concerns because there was no information forthcoming from clients on these transactions. The main question was where is the money going to eventually end up, with whom, where — that question — was never answered, was never provided by the account signatory or Jho Low despite the fact that question was posed many times but was never answered.

“And ultimately a decision was taken by higher-ups in BSI Bank because those transactions continued unabated despite concerns being expressed on the ground in terms of the veracity of these transactions,” he said.

While saying he could not comment on how BSI higher-ups discussed the suspicions after such concerns were raised, Swampillai said they had in fact encouraged instead of stopped these transactions.

“They went behind closed doors, talked about it, but ultimately they did not come down and say ‘let’s stop the transactions, let’s close these accounts’. In fact, they encouraged these transactions,” he said.

Shafee: With hindsight, you agree with me they encouraged the transactions because BSI was making loads of money?

Swampillai: Absolutely, yes.

Asked if Najib would not have to sit in the accused’s dock if BSI higher-ups had taken the trouble to check with the companies’ board of directors instead of taking Low Taek Jho’s instructions, Swampillai said he believed that SRC, 1MDB and a firm now known to be a fake Aabar would not even have opened accounts with BSI bank if the bank had insisted on imposing higher standards of control such as requiring board minutes to prove approval for every single transaction.

Swampillai had explained that from a compliance perspective, all the bank needed was for the authorised signatory of the account to sign off on transactions, instead of having to view the board’s approval for such transactions.

Shafee then asked if it was possible that Low — better known as Jho Low —had chosen BSI as its compliance standards were low.

Swampillai replied: “I think he chose the bank because I think he figured out somewhere along the line that BSI was hungry for revenue and I think he correctly deduced the bank would

compromise a little in terms of opening these accounts and carrying out those transactions.”

SRC, 1MDB subsidiaries and the fake Aabar had all opened up bank accounts at BSI bank, after the bank met with and gave a presentation to Low in 2011 on banking solutions.

Low later chose the method of fiduciary funds, where money could be sent out while hiding the identity of the sender and receiver of funds, for BSI’s new client SRC, with this same method used for other companies like 1MDB and for a purported US$2.3 billion investment — now known to be worthless — by 1MDB.

Swampillai agreed that he had the impression that the driving force to move these funds around at “light speed” was Low, based on his experience with the people he dealt with.

Shafee today challenged Swampillai’s assertion yesterday that he had the impression that Najib was aware of these huge sums of transactions by 1MDB, SRC and related companies, asking if he could really imagine that Najib would be involved in the siphoning of money out in such a detailed manner.

Swampillai maintained his views: “So when I made those statements, it was inferences, what I meant was that I didn’t think that an individual like Jho Low could command billions of dollars at whim without him having somebody that he needed to check with, run it by with, and that’s what I meant. Which is why I inferred the apex decision maker for that in terms of would have been the prime minister of Malaysia.”

Yesterday, Swampillai had listed several reasons why he believed former finance minister Najib knew about the 1MDB transactions, including Low touting himself as Najib’s adviser, and the huge sums of money and frequency of the transactions involving the Finance Ministry-owned companies which he believed would have to have approval issued by a high-ranking government official like a prime minister.

Najib’s 1MDB trial before judge Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah resumed this afternoon, with Shafee expected to continue cross-examining Swampillai.

Later in the afternoon, Swampillai told Shafee that he was merely expressing incredulity that Low would not have be answerable to someone higher up for the movement of billions of dollars, and said it did not necessarily have to be the prime minister.

“I mentioned it as an example, I didn’t say categorically to be prime minister. What I meant and I tried to explain earlier, it was incredible to me that Jho Low could make these decisions, make money move. Surely someone — given these entities were government entities — someone from the government would actually have the final say.

“So, maybe the wrong choice of words, but I sued prime minister as an example of apex approval authority, you could interchange that with director-general of Treasury department or the directors,” Swampillai suggested.

Also in the afternoon, Shafee suggested that Low’s response that the transactions were highly confidential government to government investments was a “very convenient way of shutting” BSI up to stop it from asking more questions on where the huge sums of money would eventually end up and what they would be used for.

Swampillai then revealed BSI bank was actually “threatened” when it kept asking questions about the huge sums of monies involving 1MDB and related companies, with BSI Singapore relationship manager Yak Yew Chee conveying the message from the clients of the potential consequence of persistent questions.

“Yes, in fact, if I may add, in fact there was a threat when the questions became too many and too often. Yak came back to all of us, communicated to all of us, the client — he didn’t specify who — were extremely displeased at the extent of questions and threatened to close the accounts and withdraw to a different bank. I think that effectively shut up BSI bank if not mistaken, we stopped asking questions,” Swampillai said.

Swampillai agreed this was because BSI bank was interested in the business and said it took on “wilful blindness” to what was happening, suggesting this could be the main reason why BSI lost its licence to operate in Singapore.

As for the big sums being transacted involving the 1MDB group of companies which Low insisted were for government-to-government matters, Swampillai said BSI just did not know what those funds were meant for, as it could have been for anything such as investments in another country, Islamic aid, aid projects or government-to-government projects.

“We were not in a position to decide or come to an opinion what these monies were going to, because we simply didn’t know where these monies would end up,” he said.

Believing that BSI higher-ups did discuss the question of why there was a need for the huge sums to go through fiduciary funds — where the identity of the sender and receiver of funds can be hidden — if they were truly for government-to-government matters, Swampillai said it was one of those questions which were never really answered for by the clients and which was in time ignored by BSI which then proceeded to continue with the transactions.

The trial will resume on April 17, with Swampillai to continue testifying.