KUALA LUMPUR, March 1 — Officials at 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) had treated fugitive financier Low Taek Jho, who once touted himself as Datuk Seri Najib Razak’s adviser, as though he was their “boss”, the High Court heard today.

Former BSI Singapore banker Kevin Michael Swampillai today described Low to be a man of Chinese ethnicity and “somewhat short and stout”, and said 1MDB officials were deferential towards Low — otherwise known as Jho Low — during a 2012 dinner in Kuala Lumpur.

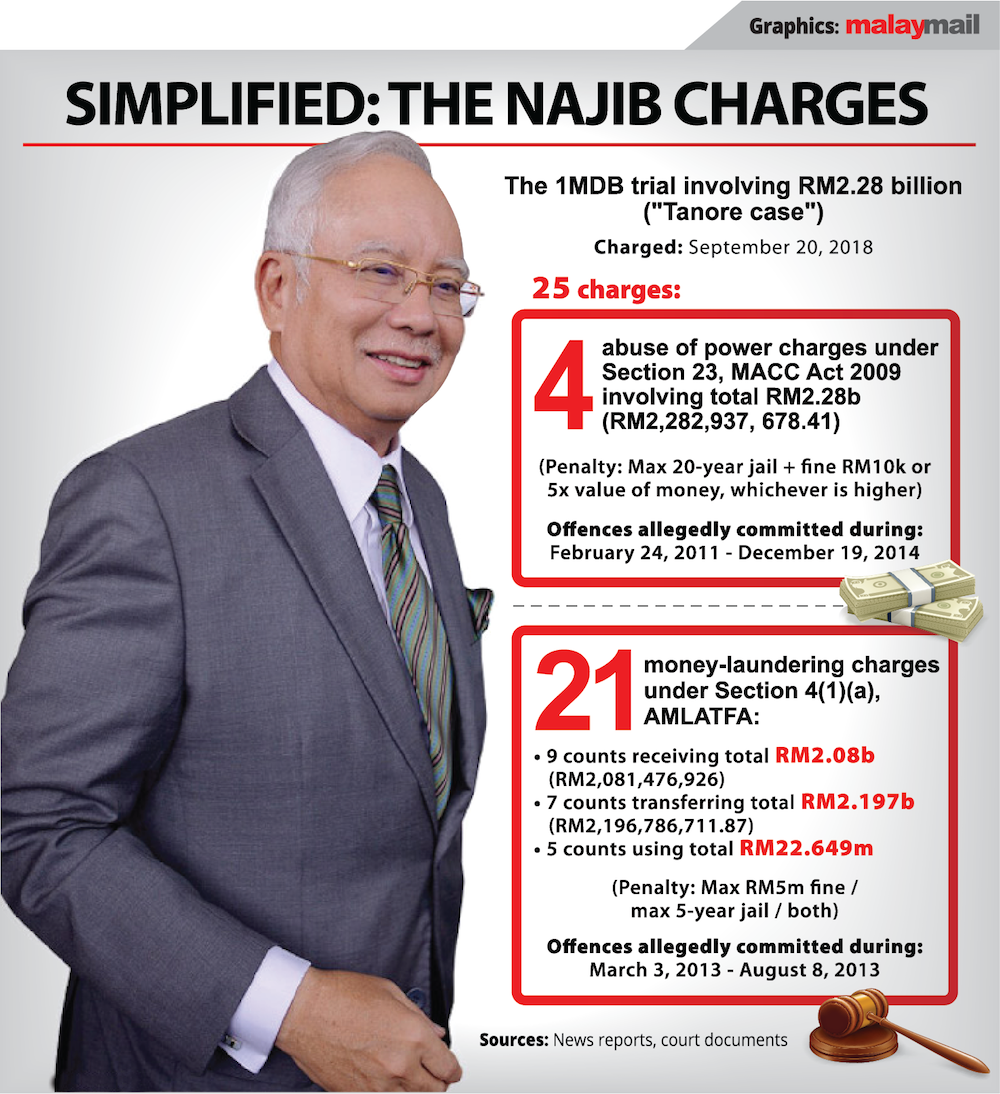

Swampillai was testifying as the 44th prosecution witness in Najib’s trial over the alleged entry of RM2.28 billion of 1MDB funds into the former prime minister’s private bank accounts.

Swampillai said he went with his BSI Singapore colleague, Yeo Jiawei, to 1MDB’s office in Kuala Lumpur to meet with the firm’s officials Jasmine Loo, Terence Geh and Azmi Tahir for a short introductory meeting in relation to PetroSaudi’s drill ships.

After the meeting, Swampillai said they went for a dinner and were ushered to a table where Low was sitting with BSI relationship manager Yak Yew Chee and Yak’s team member Yvonne Seah, with then Goldman Sachs banker Tim Leissner also present.

Swampillai said the dinner had no official purpose as it was more of “social chatter”, and assumed that Low was present in his capacity as adviser to 1MDb “as he often said”.

“Based on their interaction, I think that was the first occasion when I saw the 1MDB employees with Jho Low. That was the first time I think I saw them all together, and I formed the distinct impression that Jho Low was their boss, there was a certain amount of deference being displayed towards Jho.

“Jho was obviously the centre of attention at the dinner, he did most of the talking, everybody listened,” he told deputy public prosecutor Mohamad Mustaffa P. Kunyalam.

Asked why he formed the opinion that the 1MDB management listened to Low, Swampillai noted that Low had already positioned himself to BSI Bank that he was an adviser to 1MDB, adding: “So he was like the go-to person to discuss anything to do with these companies and accounts with BSI Bank as well as all the transactions that took place in these accounts. In fact he was quite explicitly positioned to the bank as the adviser, the go-to person.”

But for the Finance Ministry-owned companies like 1MDB and SRC International Sdn Bhd, Swampillai said he eventually felt there was someone higher than Low in terms of authority.

“As time wore on, it became more and more evident to me at least that Jho Low wasn’t perhaps the apex decision maker. You know, as I’ve made in the statement before, these are government-owned entities. I assumed, I made the assumption there was someone above Jho Low, but I don’t recall anything you know, any documentary evidence to state that fact.”

“They were government-linked entities or government-owned entities, most if not all of them fall within the auspices of the Finance Ministry of Malaysia,” he said, confirming that Najib was at that time the head of the Finance Ministry.

Swampillai, who was formerly BSI Singapore’s head of wealth management services, today shared his doubts about the legitimacy of purported “investments” by the bank’s then clients 1MDB, SRC, 1MDB subsidiary 1MDB Global Investments Limited (1MDB GIL) and Aabar Investment PJS Limited — now known to be a fake company mimicking the actual Abu Dhabi firm.

Swampillai said these entities such as SRC and 1MDB GIL had opened up bank accounts at BSI Singapore shortly after the bank gave a presentation to Low on fiduciary solutions that could be used to hide the identities of clients as the source of funds and to layer money flows.

In hindsight, Swampillai now believes that Low chose to use fiduciary funds for SRC, 1MDB and the fake Aabar to put their money in, in order to give the “optical illusion” or to trick people into thinking that the money belonging to these companies were being invested in genuine investment funds.

Ultimately, Swampillai said he “harboured suspicions” on the legality of these transactions despite the clients insisting that these were “government-to-government” investments, pointing out it was not made clear where the money pumped in by entities like 1MDB and SRC would end up after going into the fiduciary funds.

“There was no credible reason or argument advanced by the clients concerned for the amount of layering involved in these transactions.

“With the benefit of hindsight, I can safely say that there was no economic basis for these transactions, in that they were not bona fide investments that the clients attempted to portray,” he said, referring to the group of clients including 1MDB, 1MDB GIL, SRC and Aabar as not actually making genuine investments.

Instead, Swampillai said the fiduciary funds give bank clients like 1MDB and SRC the unlimited flexibility to decide when and how much money they want to send out, and that these fiduciary funds were used to send out money to recipients only known to the clients while enabling them to hide their intentions from scrutiny by Malaysia.

For example, Swampillai said it did not surprise him that after US$2.721 billion entered 1MDB GIL’s BSI bank account, a large number of transactions to send the money to fiduciary funds took place within one day of the US$2.721 billion arriving.

Based on 1MDB GIL’s BSI bank account statements, US$2.71 billion had entered in two transactions of US$2,494,250,000 and US$226,750,000 into the company’s BSI bank account on March 19, 2013, while 13 payments to transfer the money out were made the very next day on March 20, 2013 in sums ranging from US$50 million to US$161 million. The 13 transfers out totalled US$1,590,909,099 or more than half of the US$2.721 billion which had entered.

The reason Swampillai did not find it surprising was because he had observed previous transactions involving other 1MDB-related clients at BSI Bank, where cash did not remain in their BSI Bank accounts for too long but were instead quickly sent out for purported “investments”.

“There was always a great haste demonstrated by the clients to ‘invest’ the money in fiduciary funds as quickly as possible. In fact, various employees in BSI Bank were put under tremendous pressure by the clients (specifically the pressure was applied by Jho Low on Yak who in turn pressured various departments in the bank) to expedite processes so that the money flow from 1MDB GIL (and other 1MDB-related client accounts) was transferred as quickly as possible from the BSI bank account to the account of the fiduciary fund and then on to the account of the target company.

“In applying the pressure, relevant BSI staff involved in the flow of funds were constantly reminded that we were handling highly sensitive and time-bound transactions involving the sovereign wealth fund belonging to the government of Malaysia and complacency would not be tolerated by the client,” he said.

The prosecution’s case is that money originating or belonging to 1MDB had flowed through various entities and accounts including Low-linked firms and fiduciary funds before ending up in Najib’s private accounts, while Najib’s lawyers have been claiming that he had genuinely believed that the money which he received were donations from Saudi royalty.

Najib’s 1MDB trial before judge Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah resumes tomorrow, with Swampillai expected to continue to testify.