KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 17 — A report by the regional think tank Asia Centre has suggested that hate speech and ultranationalist groups are gaining significant influence in the Malaysian online space recently, promoting their agenda that revolves around the “3R”, or race, religion and the royalty.

According to the report titled “Internet Freedoms in Malaysia: Regulating Online Discourse on Race, Religion and Royalty” released yesterday, there is an immediate need for action to be taken to protect victims of the groups which have been operating with impunity.

"More exclusive and more right-wing groups use social media to propagate their agendas. These groups are able to silence people,” Dr Hew Wai Weng, a research fellow at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, was quoted as saying in the report.

"They used their ‘freedom of speech’ to limit the freedoms of other people, especially those of minority background — be it gender, ethnic or religious minorities. For example, they campaigned against LGBT people. They monitor LGBT activism online and offline.

"These right-wing groups are not necessarily state actors. There can be preachers, NGO leaders, and opinion leaders who propagate Malay Muslim insecurity,” he added.

The report also said that these groups became especially prevalent after Malay nationalist party Umno’s defeat in the 2018 general election which saw its coalition Barisan Nasional lose for the first time in six decades, which created a "vacuum where Malays need to defend Malays”.

Umno is currently part of the coalition government with former political enemies Pakatan Harapan led by Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim.

The report also pointed out that although ultranationalist groups existed before the internet, the arrival of the internet enabled these groups to promote their agenda at a low cost to a bigger audience.

This comes as 89.6 per cent of the total 32 million population in Malaysia have internet access in 2022.

The report detailed traits and tactics used by the groups, such as patrolling and monitoring the internet to promote their agenda, doxxing and attacking critics of the 3R discourse using hate speech, lodging reports with the police and internet service providers, and sometimes even call to violence.

It also noted that although Pakatan Harapan has promised to look after the rights of non-Malays, after its success in the 15th general election, the coalition’s leader Anwar has made pledges that the position of the Malays, Islam and the Royalty will not be questioned.

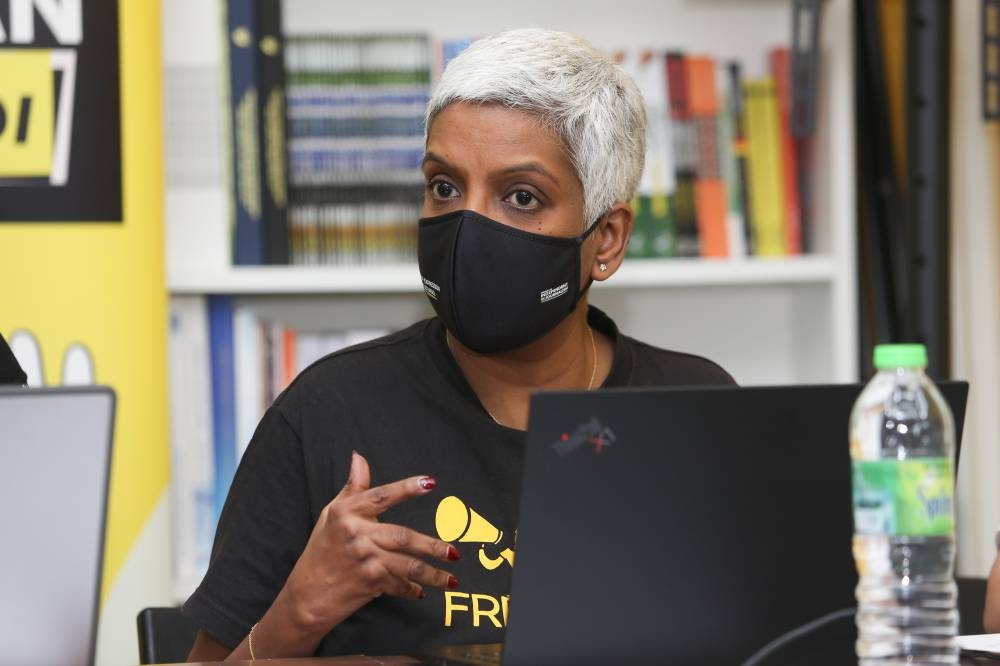

Meanwhile, Wathshlah Naidu, executive director of the Centre for Independent Journalism said that human rights activists and defenders of the internet have experienced online harassment to the point of withdrawing from participation in both online and public spaces.

"They experienced emotional and psychological impacts leading to the impact of public participation. The internet environment is contributing to a kind of spiral impact that is not only yourself but also your life in public," she said.

The think tank said the rise of ultranationalist groups was among the four impacts on internet freedoms that resulted from an ecosystem of laws used to ensure the special position of the Malays, Islam, and the monarchy, and to suppress progressive 3Rs narratives with fear.

Other impacts included website blocking by authorities, requesting social media platforms to remove content, and investigation and prosecution of critics.

The report then made several recommendations, among which was for Malaysia to sign and ratify the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Icerd) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) — which saw intense backlash from some in the Malay-Muslim lobby since 2018.

It also called for the repeal of Sections 298 and 298(A) of the Penal Code, which criminalises content or actions that authorities consider an insult to religion, as well as the repeal of the Sedition Act and the Official Secrets Act.

It also asked for a review and an amendment of Section 233 of the Communication and Multimedia Act to clearly define what are the improper uses of network facilities or network services that it criminalises.

Asia Centre said the report relied on primary and secondary data analysis carried out between August and December 2022 among others on United Nations documents, reviews of laws, reports from civil society, think tanks, government agencies and the media, and also eight key informant interviews with selected stakeholders including academics, activists, lawyers and media practitioners.