KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 29 — A nationwide survey of children who had experienced online sexual exploitation and abuse (OCSEA) found that none of them reported their ordeals either to the police or social workers, with only one respondent reporting it to a hotline.

The report titled "Disrupting Harm in Malaysia: Evidence on online child sexual exploitation and abuse" launched today found that 12 out of 38 children who had experienced OCSEA in the previous year did not even tell anyone, with those who disclosed their situation were most likely to confide in a friend (18 children) or a sibling (11).

"Some of the children surveyed who chose not to tell anyone what had happened to them attributed this to the fear that no one would believe them or understand their situation and/or to not thinking the incident was serious enough to report," said its findings.

The report said its findings corroborated previous research saying that children are not likely to turn to hotlines or helplines for support — with a 2014 national survey on cyber safety pointing out that only 3 per cent of 13,945 Malaysian school children between seven and 19 would do so.

It said out of the children who were sexually harassed or received unwanted sexual content, the most common reason given for not disclosing their experience was because they thought the incidents were not serious enough.

Why don't child victims report their experiences?

There were several barriers stopping children from reporting OCSEA, with the main ones being shame and stigma which includes victim-blaming, lack of knowledge on OCSEA, and how to deal with such incidents.

It highlighted how shame was the most commonly cited reason among children who did not tell anyone about receiving unwanted requests to share sexual images and being subjected to sexual extortion.

A criminal justice professional who remained anonymous was also quoted divulging cases in which child victims had faced “inappropriate questions in the police station, occasionally made by unethical police officers or investigative officers who would insinuate that the act and blame rest on the child victims as the reason for the cases to have occurred.”

Other reasons included the victims feeling that they had done something wrong, fear of getting into trouble and fear of creating trouble for the family.

"Children who have experienced OCSEA may feel that they themselves are responsible," it said, pointing out that 78 per cent of children and 83 per cent of caregivers believed that it is the victim’s fault when photos or videos of that they took of themselves were shared by others.

"Many children may be unwilling to disclose instances of OCSEA for fear of punishment from their caregivers, including restrictions of their internet use."

Of note was how children who were abused by an offender of the same sex may have difficulty reporting the offence due to the stigma associated with homosexuality, especially when it involves male child abuse victims due to the criminalisation of male homosexuality here.

Meanwhile, of the caregivers surveyed who would not report if their child was subjected to abuse, exploitation or harassment, 55 per cent feared repercussions and 18 per cent wanted to avoid trouble.

"This may point to a lack of knowledge of what constitutes OCSEA, and how serious it is, both among children and among the people around them,” the report said.

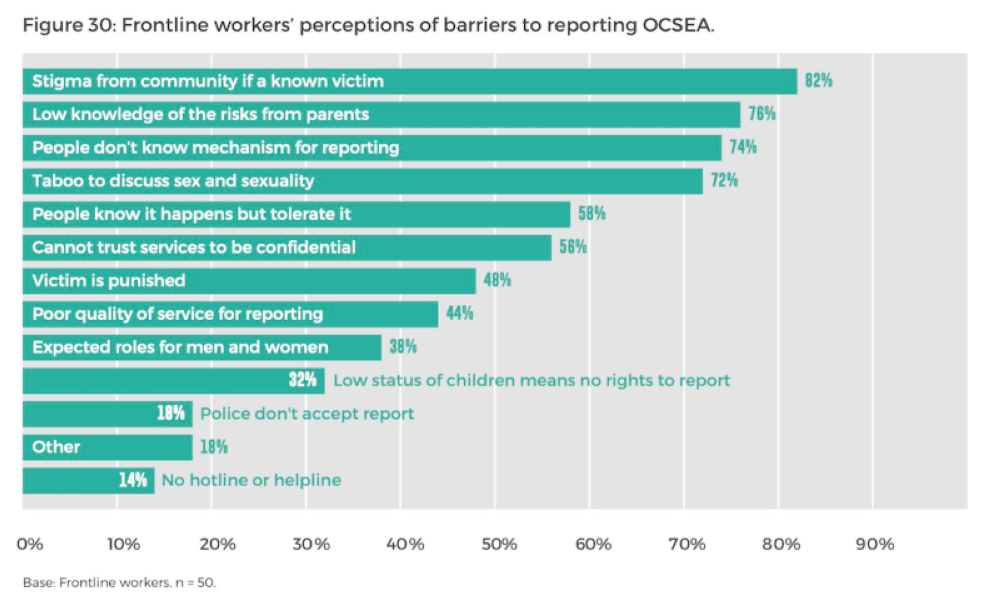

According to the frontline workers who were surveyed, 82 per cent believed that stigma influenced the reporting of OCSEA in Malaysia, making it the most commonly perceived barrier to reporting.

Further, 72 per cent of frontline workers cited taboos around sex and sexuality as a barrier to reporting.

The case for open discussions on sex, sexuality with children

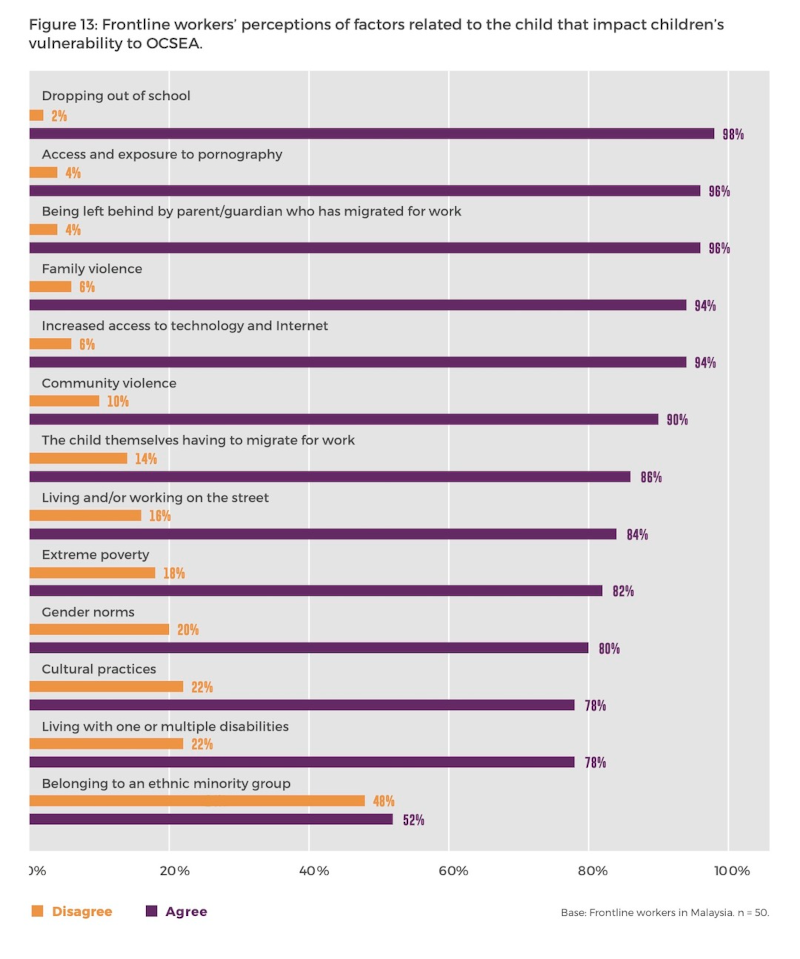

However, the report cautioned that the discomfort around open discussions of sex and sexuality would not only hinder rates of disclosure by victims but also increase children’s vulnerability to abuse and exploitation.

The research found that evidence-based awareness and education programmes must foster an environment in which children are comfortable having conversations about sexuality and asking trusted adults, including teachers, for advice.

Despite Malaysia demonstrating political will and preparedness to address OCSEA with measures such as the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 and the establishment of the Special Criminal Courts on Sexual Crimes Against Children, its promising initiatives were plagued with weak interagency cooperation and limitations related to budgetary resources, said panellist Smita Mitra, a Criminal Intelligence Specialist with Interpol.

In a recent forum discussing the findings, Andrea Varrella, ECPAT Legal Research Coordinator, shared that these issues could be alleviated by allocating financial resources for normal courts to be more child-friendly, by equipping legal professionals with technical knowledge and skills necessary to handle OCSEA cases and empowering the Malaysian Internet Crime Against Children Investigations Unit with sufficient personnel and expertise.

In terms of raising awareness, panellist Datuk Dr Raj Abdul Karim, Chair of End CSEC Network Malaysia and ECPAT International Malaysia, lamented that the Ministry of Education's planned sex education curriculum based on international standards was unable to be implemented due to political, religious and traditional constraints.

"It’s not only a question of giving them information about pregnancy and protecting against contracting HIV/AIDS et cetera, but also to strengthen their own confidence and their own ability to recognise risks online and offline of those who are trying to abuse and exploit them,” she said.

The US$7 million (RM32 million) study was funded by the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children and was carried out through the partnership of civil group End Child Prostitution in Asian Tourism (ECPAT) International, the Interpol and United Nations' Children’s Fund's (Unicef) Office of Research.

In Malaysia, researchers interviewed 995 children aged between 12 and 17 who had used the internet in the three months prior, in addition to ten semi-structured interviews with 11 criminal justice professionals, a survey of 50 frontline service providers that included outreach youth workers, social workers, and health and legal professionals working with children’s cases, and interviews with 18 government officials.