KOTA KINABALU, May 28 ― Sabah, the state that ostensibly sparked the third wave of Covid-19 in the country due to a snap election, is far behind in terms of vaccine registrations on MySejahtera compared to any other state.

As at May 25, just 17.56 per cent in Sabah have registered to be immunised, which is far behind the next lowest state which is Kelantan at 29.62 per cent.

The 515,124 who registered out of some 2.9 million who qualify is also far behind Sabah’s neighbouring Sarawak, which has registered 56.57 per cent, or 1.17 million people.

The numbers are somewhat jarring, given that in October and November last year, Sabah continuously recorded the highest daily number of Covid-19 cases nationwide each day, hitting a peak at 1,199 on November 6 before dropping back to three digits for the remaining time.

Vaccines started arriving in Sabah as early as March, but by March 18, only 9.1 per cent (or 267,386) had registered. A month later, it increased to 14.6 per cent or 419,143 people. On May 18, it was 16.2 per cent or 495,294 people.

As of May 25, the number stands at 17.56 per cent.

The figures also differ by districts ― urban districts like Kota Kinabalu and Putatan show 25 per cent and 42 per cent registration respectively, while Kinabatangan, a far flung rural district on the east coast only showed 5. 5 per cent registration.

What are some of the reasons behind the hesitancy?

Sabah Covid-19 spokesman Datuk Masidi Manjun said that the numbers were not reflective of the work and effort that health officers had put in on the ground to get people aware of the vaccine and physically sign them up.

“Most people prefer to register manually, especially in rural areas,” he said when contacted. He said that due to the manual labour involved, the number has not been factored into the system yet.

Malay Mail has reached out to the Health Department for statistics by districts in order to get a better picture.

Meanwhile, it is apparent to many that Sabah with its majority population in rural and semi-rural areas, lacks the infrastructure, and access to information that is needed to roll out such a monumental vaccination programme.

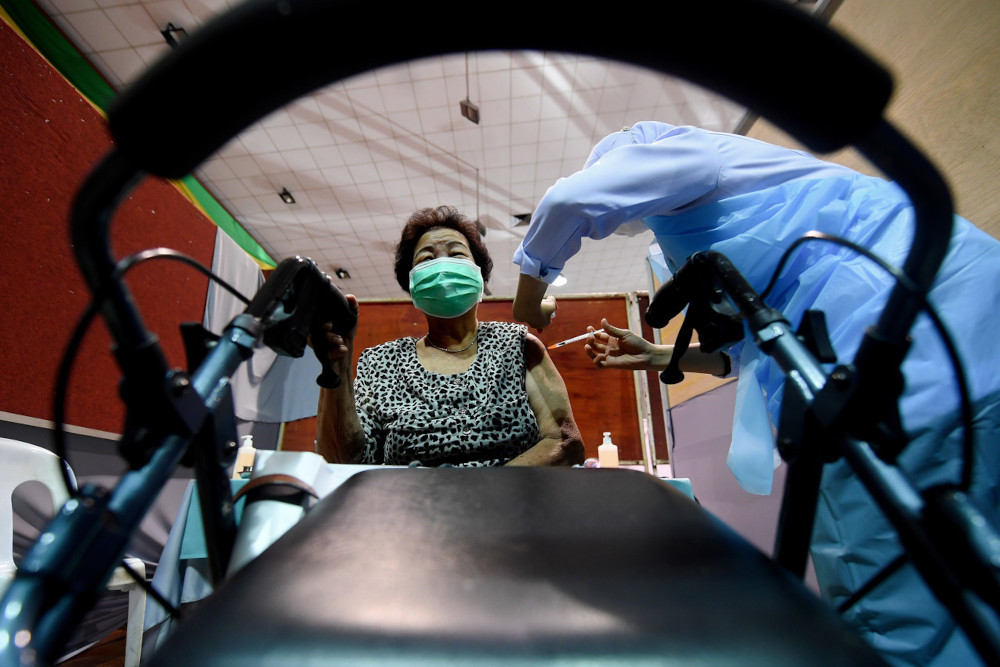

People that Malay Mail spoke to who had yet to register have many reasons why they have yet to register ― some are adopting a lackadaisical attitude, either out of fear of side effects or just plain procrastination, while others, mostly the elderly or those in rural districts, either do not have access to a smartphone or can’t be bothered to figure out how to work the app.

“I’m not against it, I don’t know. I read about some side effects so let’s see what happens,” said one urban mother of two who juggles housewife duties and a side business.

A middle-aged businessman from here said that many of his friends who registered have yet to have gotten an appointment yet so there was no point in rushing.

“It’s not as if they are going first-come-first-serve,” he said.

An elderly retired uncle, whose children have registered but not himself, said he was waiting for news of the Sinovac vaccine to be widely available before he goes for the jab.

But those are the laments of any middle-class urban-dweller anywhere.

In the interiors, Covid-19 just not part of conversations

In Sabah, the second largest state in Malaysia whose land mass is bigger than Selangor, Negri Sembilan, Perlis and Melaka combined, the population is spread out and many live in the rural areas, where internet and access to news and information is spotty.

Subsistence farmers like Obot Jefferi Joakim, 45 from Upper Moyog lives in a village 30 minutes walk from the main road through a river, several streams and dense secondary jungle and while he and his family has not been able to escape from the news of Covid-19 and its effects, it is not a big part of their daily conversation or life.

To him and his village of some 40 people, checking into an app and social distancing is a foreign concept that is hard to grasp, and vaccination an option they have only heard about in passing.

“I won’t say no, but I don’t think it is a priority. If they come to me, then sure, if it's for my own good, why not? I’ve got relatives in Kota Kinabalu who have taken it, and nothing happened to them, so ok.

“But if you ask me to do this and that … I don’t know. I know it’s free, but its a lot of effort,” he said.

To people like him and the majority of Sabahans who live in rural areas, a vaccine they have not heard of to a disease they don’t feel threatened by, is simply not a priority.

It also helps that no one in his family or village has been infected by Covid-19.

Kadamaian assemblyman Datuk Ewon Benedick said that it is a combination of the “wait and see” attitude, lack of awareness and access that makes it so challenging to get a state like Sabah vaccinated for herd immunity.

“In most kampungs in rural areas, you really need to go to them to convince them in person. With restrictions in place like no gathering, churches and suraus being limited and with the health department fully occupied, no physical awareness programme being carried out to that kampungs,” said the Upko vice-president.

Then, it is a matter of not having a smartphone or not being tech-savvy enough to maneuver through the app and then the registration.

“Then the answer is to do it for them, or manually register them, but not all the villages have clinics where they can get manually registered. And with travel restrictions, many can’t make it to the nearest health clinics even,” he said.

“People in the grassroots, the personal touch is important. A grassroot engagement is necessary for things like vaccines. Maybe you even need a spiritual leader like an imam/priest to convince their faith,” he said.

Kepayan state representative Jannie Lasimbang, who is no stranger to working with indigenous communities concurs that it is definitely that lack of connection both technologically and socially, to the grassroots that has Sabah so behind.

She said that the registration rate in urban areas is decent but the main problem is rural areas, like Obot’s lack of internet connectivity and therefore, access to information.

“I think they have not even scratched the surface for rural areas yet. Do the 60 per cent rural population actually have access to registration?,” she asked

“If the government is relying on MySejahtera App, the registration is expected to be low,” said the Sabah DAP Wanita chief.

Lasimbang is from Penampang, a district just outside the city centre, where Obot lives, where many villages are just 30 minutes off road but may render one without internet or even running tap water.

“In Sabah, the new government changed the local leaders like the ketua kampung, and village development and security committees have not been appointed yet so they can’t rely on them for manual registrations either,” she said.