PUTRAJAYA, Dec 16 — A Malaysian woman who was born to a Muslim man and a Buddhist woman was never a Muslim to begin with as the parents were not married and as she was an illegitimate child, and the declaration of her religious status as a non-Muslim should be made by the civil courts instead of the Shariah courts, the Federal Court heard today.

In this case, 39-year-old Rosliza Ibrahim has an identity card that states her religion as Islam, and has been waiting in a five-year legal battle for the civil courts to declare that she was never a Muslim and is not a Muslim, and that all Selangor state laws for Muslims do not apply to her and that Selangor Shariah courts have no jurisdiction over her.

At the High Court, Rosliza had shown proof that the Islamic religious authorities of the Federal Territories and 11 states (Selangor, Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Melaka, Negri Sembilan, Pahang, Penang, Perak, Perlis and Terengganu) do not have any records of her mother converting to Islam or of her biological parents entering into a Muslim marriage, as well as provided the court with her late mother’s October 8, 2008 statutory declaration of not being married to Rosliza’s father when she was born.

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal had previously in June 2017 and April 2018 respectively ruled against Rosliza, which led to the hearing of her appeal today involving two legal questions before the Federal Court.

Civil courts vs Shariah courts

One of the key questions of law today in the Federal Court was whether the High Court has exclusive jurisdiction — or is the only court with the powers — to hear and decide on a matter if it is about “whether a person is or is not a Muslim under the law” instead of “whether a person is no longer a Muslim”, based on the Federal Constitution.

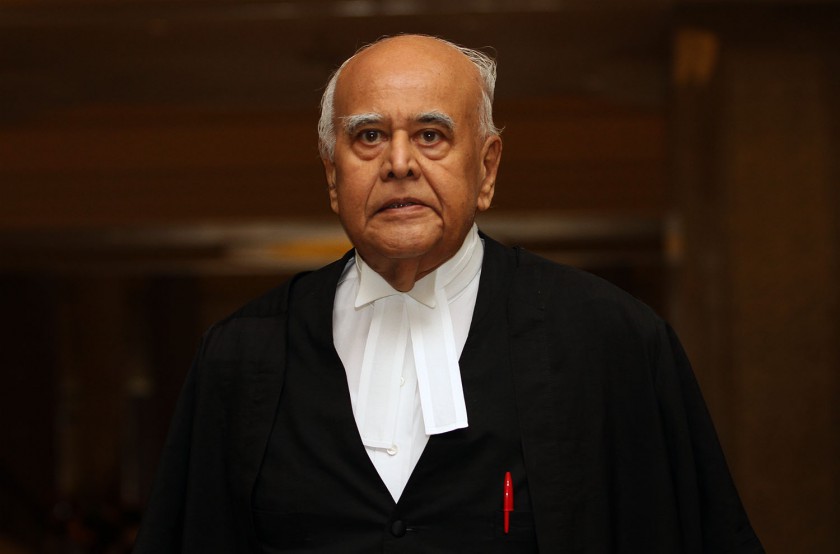

Rosliza's lawyer Datuk Seri Gopal Sri Ram today argued that both the High Court and Court of Appeal had wrongly categorised her case as being a Muslim seeking to stop being a Muslim and that this had resulted in them deciding that she could not get the civil courts to make a declaration on her religious status.

But Sri Ram said that Rosliza's case was different from the case of Lina Joy, where a Malay who was initially a Muslim had renounced the faith of Islam and where the Federal Court had in a 2-1 majority decision ruled in 2007 that such matters are for the Shariah courts to decide.

In Lina Joy's case, she went to court after the National Registration Department (NRD) allowed her to change her name but refused to remove the word “Islam” and her original name from her identity card, as the NRD insisted on Lina producing an order from the Shariah court regarding her renunciation of Islam even though she had filled in the IC application form with her religion stated as Christianity and a previous statutory declaration that she had renounced the faith of Islam.

Sri Ram argued that the lower courts' misclassification of his client's case resulted in them ruling that the civil courts cannot decide on Rosliza's religious status and that she should go to the Shariah courts.

“Our submission is that this is not a case of an exit of religion, rather it's a case where the applicant contends that she never belonged to the religion of Islam.

“This classification led to a fundamental error on the part of the courts below in refusing to seize themselves of jurisdiction and instead hold that the Shariah court was seized of jurisdiction on the facts,” he said.

Sri Ram said the Federal Court's majority decision in Lina Joy was wrong as it treated the civil courts' judicial powers as having been ceded entirely or given entirely to the Shariah court, and that it was wrong to interpret the Federal Constitution as having implicitly given the Shariah courts jurisdiction in the matters in that case as such jurisdiction have to be expressly mentioned in law.

But even if it is a case related to the act of leaving Islam, Sri Ram said the High Court in the civil courts still has the jurisdiction to hear and decide on the matter.

According to court documents by Rosliza’s lawyers, it was asserted that both she and her mother never converted to Islam and that there was no valid marriage between her parents, and that she was raised as a Buddhist since birth, and that the application form for her identity card cannot be considered as proof of her actual religion as it was allegedly riddled with conflicting details and inconsistent handwritings.

.jpg)

Was Rosliza a Muslim in the first place or not?

During the hearing today, the Federal Court judges repeatedly brought the attention of the lawyers for the Selangor government and the Selangor Islamic Religious Council (Mais) to the specific questions of law that were being examined in the appeal, and sought clarification from them.

Selangor state legal adviser, Datuk Salim Soib @ Hamid, who was appearing for the Selangor state government, insisted that Rosliza was a Muslim when she was born.

To justify his arguments, Salim cited Section 2 of the Administration of the Religion of Islam (State of Selangor) Enactment 2003, where one of the definitions of “Muslim” was stated as being a person whose parents — either one or both parents — were a Muslim at the time of the person's birth.

Chief Judge of Malaya Tan Sri Azahar Mohamed then asked what the religious status of Rosliza would be when she is born illegitimate as there is no valid marriage between the Muslim father and Buddhist mother.

Salim then again insisted that Rosliza was born a Muslim due to Section 2 as she allegedly took on her father's religion and argued that only the Shariah courts have the powers to decide on her religious status.

Chief Justice Tun Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat however highlighted that the general principle under Islam is that a Muslim father and non-Muslim mother could not have been married because one of them is a non-Muslim, and that in such a case, the child would under Islamic principles be born illegitimate and be unable to take on the Muslim father's religion but would follow the mother's religion.

Salim went on to argue that if the marriage is being disputed, the case should be referred to the Shariah court to determine the validity of the marriage.

Azahar highlighted however that Rosliza's mother had provided a statutory declaration to the courts that she is not a Muslim and that she never married Rosliza's father, and that there was also evidence from 11 state Islamic religious councils in Malaysia that showed that there is no record of any marriage between Rosliza's mother and father.

As Salim again said the Shariah court should determine the validity of the marriage, Tengku Maimun pointed out that Rosliza would naturally not fall under the Shariah court's jurisdiction, as she would be following her non-Muslim mother's religion due to her illegitimate birth to the non-Muslim mother and Muslim father.

Salim then sought to rely on the application for Rosliza’s identity card filled in by her father where her father was stated as a Muslim who was stated as married to her mother, asserting that the truth of the contents of the identity card documents would depend on the applicant giving correct information for the application.

Tengku Maimun however highlighted that cannot be the case as it would mean that even false information provided by a person applying for an identity card would be taken to be conclusive, then pointing out that Regulation 24(1) of the National Registration Regulations 1990 states that the person who claims the IC contents to be true has the burden of proving the truth of the contents.

Tengku Maimun said that Regulation 24(1) meant that the Selangor state government has the burden of proving Rosliza's IC contents to be true, but Salim disagreed.

.jpg)

Was the Muslim father and non-Muslim mother ever married?

In another lengthy exchange with the judges, Mais lawyer Abdul Rahim Sinwan insisted that Rosliza's parents were married and that Rosliza was born a Muslim, by citing the information filled up in the IC application form.

Abdul Rahim also insisted that there could be a valid marriage even without proof of marriage through a marriage certificate, claiming that Islam allows for a valid marriage even without it being registered if both parties agree they are married and that they could prove such an unregistered marriage by calling in witnesses in the Shariah court.

Tengku Maimun questioned the effect of such a line of argument, asking: “So taking this analogy, my question would be when there is a raid, and you say there is an offence of khalwat (close proximity) and cannot produce marriage certificate, but the marriage could very well be valid under Islamic law?”

“Yes, it is,” Abdul Rahim replied when confirming his argument of an undocumented marriage having the possibility of being valid in Islam.

When asked by Tengku Maimun, Abdul Rahim agreed however that a non-Muslim cannot marry with a Muslim based on the general principles of Islamic law, and that the child born from such a couple would be illegitimate and that the child would then follow the mother's religion instead of the father's religion.

Abdul Rahim however argued that Rosliza was not an illegitimate child, again insisting that she is Muslim due to her father being Muslim.

Senior federal counsel Suzana Atan, who represented the attorney general as amicus curiae, said that an illegitimate child would follow the religion of the mother and agreed that Rosliza would never be a Muslim to begin with if she is illegitimate.

Suzana agreed that the burden of proving the contents of Rosliza's IC would be on the Selangor state government and Mais based on Regulation 24(1) since they are claiming the IC contents to be true, before citing the IC application form filled in by Rosliza's father as proof of the truth of the IC contents.

Lawyer Philip Koh, who held a watching brief for the Malaysian Consultative Council of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Sikhism and Taoism (MCCBCHST), highlighted Section 2(2) of the 2003 Selangor enactment to say that definitions of terms in that law are required to not conflict with hukum Syarak or Islamic law.

Koh suggested that Section 2 regarding the definition of Muslim — where one or both of the parents of the person is a Muslim at the person's birth — should be read consistently with hukum Syarak or Islamic law where an illegitimate child would follow the mother's religion.

Lawyer Mansoor Saat appeared today for the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) as an amicus curiae.

After hearing the arguments, the Federal Court said it would deliver its decision at a later date.

The other judges on today’s nine-member panel were President of Court of Appeal Tan Sri Rohana Yusuf, and Federal Court judges Datuk Nallini Pathmanathan, Datuk Abdul Rahman Sebli, Datuk Zabariah Mohd Yusof, Datuk Seri Hasnah Mohammed Hashim, Datuk Mary Lim Thiam Suan and Datuk Rhodzariah Bujang.

.JPG)