KUALA LUMPUR, Aug 16 — Amid PAS’ continued push to implement strict Shariah criminal penalties in the two states it currently controls, a research by the Penang Institute released today found variations in the prescriptions of its implementation across the three countries in South-east Asia despite belonging to the same Shafi’i Islamic school of thought.

The study, focusing primarily on hudud punishments on theft and robbery in Brunei, Aceh in Indonesia, and Malaysia’s Kelantan and Terengganu, revealed that although the law is supposed to be enforced in accordance with Islam, its implementation differs in all four jurisdictions.

While they each share similar basis from Quranic verses and hadiths, there are still several notable differences including the scope of jurisdiction, punishable offences and types of penalties.

Penang Institute analyst Nidhal Mujahid who wrote the report, said that today’s hudud law cannot simply be deduced as God’s commands.

“It is also unlike how it was previously done in the prophet's time because its implementation requires human reasoning (ijtihad).

“Hudud’s jurisdiction may be influenced by the difference in school of thoughts and jurists compatibility with local context and existing laws,” he said in the 14-page-long report.

Aceh, for instance, uses hudud law as a blanket ruling to both Muslims and non-Muslims, with the exception of those mentally-ill.

However, the Penang Institute study said Aceh does not have specific provisions to penalise theft and robbery.

It added that hudud law in Indonesia’s westernmost province limits punishment for those crimes to caning, fine, and jail terms.

.jpg) Nidhal said heavier penalties often associated with hudud, such as amputation of limbs or stoning, are not provided for by Aceh’s existing laws.

Nidhal said heavier penalties often associated with hudud, such as amputation of limbs or stoning, are not provided for by Aceh’s existing laws.

“This is probably made possible due to the limited provision in the Helsinki Agreement, a form of human reasoning which eventually brought peace to Aceh,” he said.

The Helsinki Agreement refers to the August 15, 2005 accord signed by the Gerakan Aceh Merdeka which sought autonomous rule from Jakarta, and the Indonesian government to end conflict in the Sumatran province that had been taken place since 1976.

Nidhal said this also showed that hudud supporters in Aceh had carefully weighed in all factors, including the local context, prior to its implementation.

“If such pragmatism is acceptable in fine-tuning the implementation, is it not acceptable that hudud implementation can be deferred if it does not meet the syariah objectives?” he asked.

In Brunei, theft is an offence that “involves public space and or the lives of others”, therefore its penalties are applicable to both Muslims and non-Muslims.

First time offenders may have his or her hand amputated, while repeat offenders may additionally have their feet chopped off.

Brunei’s hudud law, however, grants an exception to its sultan for he is deemed “infallible” by the nation’s ordinances.

In Terengganu and Kelantan, the exact same punishments await Muslim thieves.

Generally, all Malaysian Muslims are bound by hudud law but the Yang di-Pertuan Agong and the Malay Rulers are protected by the Federal Constitution.

According to Article 182 (2), any proceedings involving the Yang di-Pertua Agong or Malay Rulers will need to go through the Special Courts.

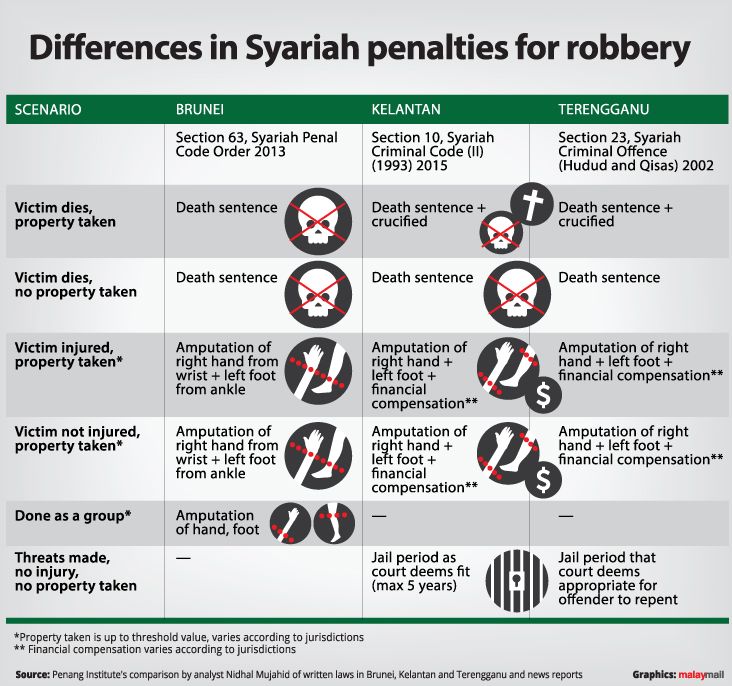

The study added that the distinction can further be seen in the penalties for robberies and other serious crimes.

In Terengganu and Kelantan, for instance, offenders who murder and forcibly seized other’s properties not only face a death sentence, but they will also be crucified.

Those who rob others without causing hurt are required to pay financial compensation (diyat), on top of having their limbs chopped off, if the robbery value exceeds a certain threshold.

Those who rob others without causing hurt are required to pay financial compensation (diyat), on top of having their limbs chopped off, if the robbery value exceeds a certain threshold.

The financial compensation also varies in all three jurisdictions.

In Brunei, 1 Diyat is equivalent to 100 Dinar or 4250 grams of gold or B$340,000 (RM1,014,733).

In Kelantan, 1 Diyat is equivalent to 4450 grams of gold or RM 703,434, while in Terengganu, 1 Diyat is the equivalent of 100 camels or RM 590,000.

Hudud law has become a controversial topic in Malaysia since PAS president Datuk Seri Abdul Awang Hadi first sought to amend the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965, also known as Act 355, in 2016 through a private member’s Bill.

The Marang MP has repeatedly said he is only seeking to empower the Shariah courts to mete out stricter penalties.

Critics have said that the proposed amendments to Act 355 are a backdoor to the implementation to hudud, to which Abdul Hadi has repeatedly denied.

Over the past two years, the Bill has been listed in the Dewan Rakyat’s Order Paper four times.

It, however, was left in limbo after deferred by former Dewan Rakyat Speaker Tan Sri Pandikar Amin in April to the next Parliamentary meeting, without reaching its turn to be debated.

At the moment, Terengganu and Kelantan cannot implement their respective hudud laws until Bill 355 is tabled and passed in the Parliament, following the separation of jurisdiction between the central and state governments.

.jpg)