KUALA LUMPUR, Aug 22 — Jay Jay Denis used to go to private hospitals to treat his spinal and nerve injuries, but switched to public facilities in 2015 when medical fees became too expensive and his insurance could not cover everything.

However, the 24-year-old policy researcher has now taken to self-medicating, saying he could not afford the long waits — once as long as three hours at University Malaya Medical Centre’s (UMMC) emergency ward — to treat the back spasms that required him to use crutches.

The UMMC is a university hospital in Petaling Jaya.

“Previously, I would be attended to by a general practitioner or specialist within one hour but since that visit, a subsequent experience of a similar waiting time meant that I now try as best to manage the problem on my own through research online, and purchase the medicines at a pharmacy, or visit a chiropractor,” Denis told Malay Mail Online.

Denis, who used to visit his doctor every two to three months, said he could not afford the medical leave necessary for the multi hour waits because he was working more than one job and has deadlines to meet, besides being wary about abusing his allotted leave.

When asked if he was afraid of misdiagnosing himself by doing online research, he said it was a risk worth taking for the time and money saved.

“So far, I’ve been lucky with online research, although doctors don’t recommend it at all. But perhaps because I [have a] job as a researcher, [it] helps me vet through before self-diagnosing and buying medicines to cure the pain,” said Denis.

One in five don’t go to clinics or hospitals

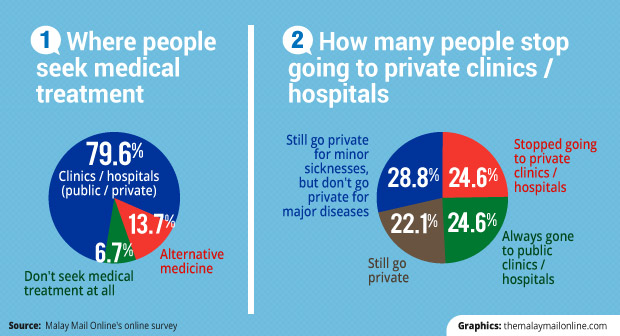

Denis’ experience of quitting formal medical treatment for major health issues because of long waiting times at public hospitals is shared by about 20 per cent of respondents in a Malay Mail Online survey, who said they do not seek medical treatment at all or rely on alternative medicine.

In the online survey that ran from August 16-18 and received 358 responses, around 26 per cent cited excessive waits as the reason they stopped seeking medical treatment at public clinics or hospitals in the last 12 months. About 16 per cent said they could not afford to take a full day’s leave to get treatment because they are not paid for time off.or their employer did not allow them to do so.

On the average waiting time to see a doctor at public clinics or hospitals in the last 12 months, about 40 per cent said they waited four hours, about 26 per cent waited for an hour, about 8 per cent less than an hour, and about 7 per cent between two and four hours.

Two per cent said they waited for eight hours.

Just over half said they switched from private clinics or hospitals to public institutions in the last 12 months, mainly because they could not afford the medical fees.

Just over half said they switched from private clinics or hospitals to public institutions in the last 12 months, mainly because they could not afford the medical fees.

A total of 9.5 per cent said they stopped seeking treatment at public facilities shortly after making the switch from private to public, while nearly 6 per cent have completely stopped visiting any clinic or hospital.

The clinics or hospitals most frequently visited by respondents were located in Selangor (35.5 per cent) and Kuala Lumpur (about 29 per cent).

Getting up at 5.30am to beat the queue

Lyn Chan, 56, sometimes gets up at 5.30am to prepare a breakfast with a special diet for her husband who suffers from diabetes, kidney disease and has suffered strokes in 2008, 2014 and again this month.

She must do so if she plans to arrive at UMMC by 7.30am or 7.45 am just so she can see the doctor in three hours by 10.30am or 11am.

She said even if her 64-year-old husband gets an 8am appointment, there is regularly a crowd already waiting for queue numbers when the dispenser opens at 7.30am.

“Even for a blood test, it’s two hours or more,” Chan told Malay Mail Online.

“The waiting time is just very long even though there’s an appointment set,” she said.

Chan added that an appointment was essentially a guarantee that you will see a doctor on the day, but not at the appointed time.

Chan recalled when her husband had his first major stroke in 2014 and they entered the accident & emergency (A&E) department at 7.30pm that was fully packed then. She said the doctors took some blood tests but did not see him till some two hours later, after which they ordered more tests before diagnosing him at midnight.

They then had to wait for a bed to be ready. Chan said her husband was only warded at 5.30am, which meant they were in the hospital for almost 10 hours.

The process of seeing a doctor

According to Chan, upon arriving at the university hospital, one takes a queue number to see a nurse who will register, look up the patient’s files and documents, and assign him to a doctor or clinic. This can take 15 to 30 minutes, depending on when one arrives at the hospital and the queue length.

At the next station, a specific doctor and room is assigned, which takes another 15 to 30 minutes, again depending to the time of day and queue length.

Then, the patient is sent to the waiting area outside the doctor’s consultation room, where the wait can be between one and three hours. On average, Chan said the total time waiting was three to four hours before meeting the doctor.

The actual consultation with the doctor will take between 15 and 30 minutes, depending on the patient’s problems.

After seeing the doctor, Chan said she would wait for 15 to 30 minutes to collect medication, noting that prescriptions are fast as they are done online.

“The waiting game at the clinic, you just have no choice because you can’t afford medical fees in the private sector,” she said.

Living on EPF money

She pointed out that when her husband suffered the 2014 stroke, she sent him to the Gleneagles Kuala Lumpur private hospital a couple of weeks after he went to UMMC. His treatment at UMMC, including a week’s stay, medicine, tests and scans (excluding MRI) cost RM1,500. At the private hospital, the bill was close to RM5,000 for half as long, but included the RM1,500 for the MRI.

Now, Chan’s husband’s clinical check-ups (once every three months for each of five to six different clinics), three therapy sessions a week, medicine, and most scans (except for MRI that is charged at RM500) at UMMC are all free because he has been categorised an “OKU” (disabled person).

“We’re at the hospital almost every day,” she said.

The couple who live in Shah Alam do not have medical insurance. Since Chan is a full-time carer for her husband who cannot work, she has been dipping into her Employee Provident Fund (EPF) savings, which is meant for retirement, to support both of them. They still pay almost RM6,000 monthly for their housing loan that have a few more years to go. Her husband has depleted his EPF funds.

Chan is also doing part-time teaching at a floral arrangement school that earns her some RM2,000 monthly, which “can help with groceries”.

When her EPF and unit trusts run out, she said she will be forced to sell a condominium that she bought as investment when she first started working. And if the RM500,000 or RM600,000 from the sale of that condominium runs out, she said they will have no choice but to sell their marital home and start renting.

“We don’t have medical insurance. When you’re young, you don’t think about it.

“But it doesn’t release the fact that the government should do something and push it. If they can come up with something like EPF, why can’t they do something like that for medical and push us to contribute 0.5 or 1 per cent more?” Chan questioned.