MIRI, Aug 5 — The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) says a reason for statelessness in Sabah and Sarawak is that ‘their extensive geographical land areas have limited rural people from both states access to the registration office located in the city’.

The Orang Ulu, for instance, originally settled in remote and isolated locations, often deep in the heart of rainforests or high in the mountains in Sarawak, leaving them disconnected from the bureaucratic processes required to assert their legal status.

While most parts of Malaysia and Sarawak have developed, rural constituencies such as Baram, Belaga, and small towns like Lawas as well as Limbang, where most Orang Ulu communities live, infrastructural development and access to basic amenities remain a challenge.

In the Parliament sitting last March, Baram MP Datuk Anyi Ngau pointed out that his constituency continued to be left far behind in terms of development from the rest of the country.

He lamented that the community still relied very much on logging roads as their main link to the outside world, something that has persisted for more than six decades.

In the past, Orang Ulu villages and settlements were only accessible after days or even weeks of travel by longboat or jungle trekking.

Today, even though these longhouses and settlements have logging road access, only four-wheel drive vehicles (4WDs) can withstand the unforgiving terrain.

Geographical isolation

Due to the long and challenging road conditions, the cost of transportation to visit the nearest National Registration Department (NRD) Office to register one’s newborn was costly and beyond most villagers.

Many of the Orang Ulu in the past also had limited access to formal education, due to their geographical isolation.

For example, many children from the Penan community, the last nomadic indigenous tribe in Sarawak, did not complete their primary and secondary school education.

A former Penan village chief, Belaweng Turau, 54, said many Penans, especially the older generation, never attended school.

“When I was a young boy, I remember our parents were still living in the jungle, and we would follow them wherever they took us. We moved from one jungle to another and therefore, it was difficult to attend school.

“Furthermore, the schools were located very far from where we settled.

“I remember when I attended the first few years of primary school, my parents had to walk with me for five hours to get to the school,” he said.

Inter-generational statelessness: A persisting problem

Another reason why the older Penan generations did not go to school in the past was because they were scared to come out of the jungle and live with other communities, said Belaweng.

History professor, Ooi Keat Gin, in his article entitled ‘Education in Sarawak During the Period of Colonial Administration 1946-1963, stated that although the number of native children attending school was considerably larger than during the Brooke period (1841-1946), the problems of irregular attendance and the tendency to withdraw before the full primary course persisted throughout the Colonial period.

The professor pointed out that the illiteracy rate among the indigenous communities of Sarawak prior to the formation of Malaysia in 1963 was at 98 per cent.

Without the ability to read and write, the older generation of Orang Ulu had no knowledge of the importance of registering their identity or the birth of their children and, in most cases, registering their marriages, which then resulted in inter-generational statelessness

Marriage woes

Sarawak’s Minister of Women, Childhood and Community Wellbeing Development Dato Sri Fatimah Abdullah was quoted in a news article published in The Borneo Post, as saying that another cause of child statelessness in the state was cross-border marriages that had gone unregistered.

She said such cases occurred in communities near the border with Indonesia.

“This has led to the child becoming stateless, and the procedure to register would become complicated as it would require various documents to prove the status of the child,” she said.

Some couples could not register their marriage legally because one partner, usually the woman, is stateless or undocumented.

To register a marriage at the NRD, both partners must be citizens. In the case the woman is a foreigner, she has to produce sufficient documents to enable the registration to go through.

“There were cases where couples wanted to register their marriage legally, but because of the complexity of the woman’s status, such as her being stateless, they ultimately could not.

“Hence, resulting in the children born out of wedlock and inheriting their mother’s citizenship status. This cycle will continue to the next generations,” said activist Agnes Padan.

Traditional and customary marriages that are not recognised by the law could also result in statelessness, especially among children.

Sarawak, for example, has three legal systems related to marriage: civil, syariah and customary marriages.

According to the Council for Native Customs and Traditions, non-Malaysians cannot marry Sarawak natives according to custom after Sept 21, 2006; otherwise, the marriage is invalid.

Some couples have resorted to marrying according to custom because the civil law does not allow them to get married due to lack of documents, especially when the woman is stateless or undocumented.

The NRD has also long been criticised for its inconsistent procedures in receiving, reviewing and approving citizenship applications.

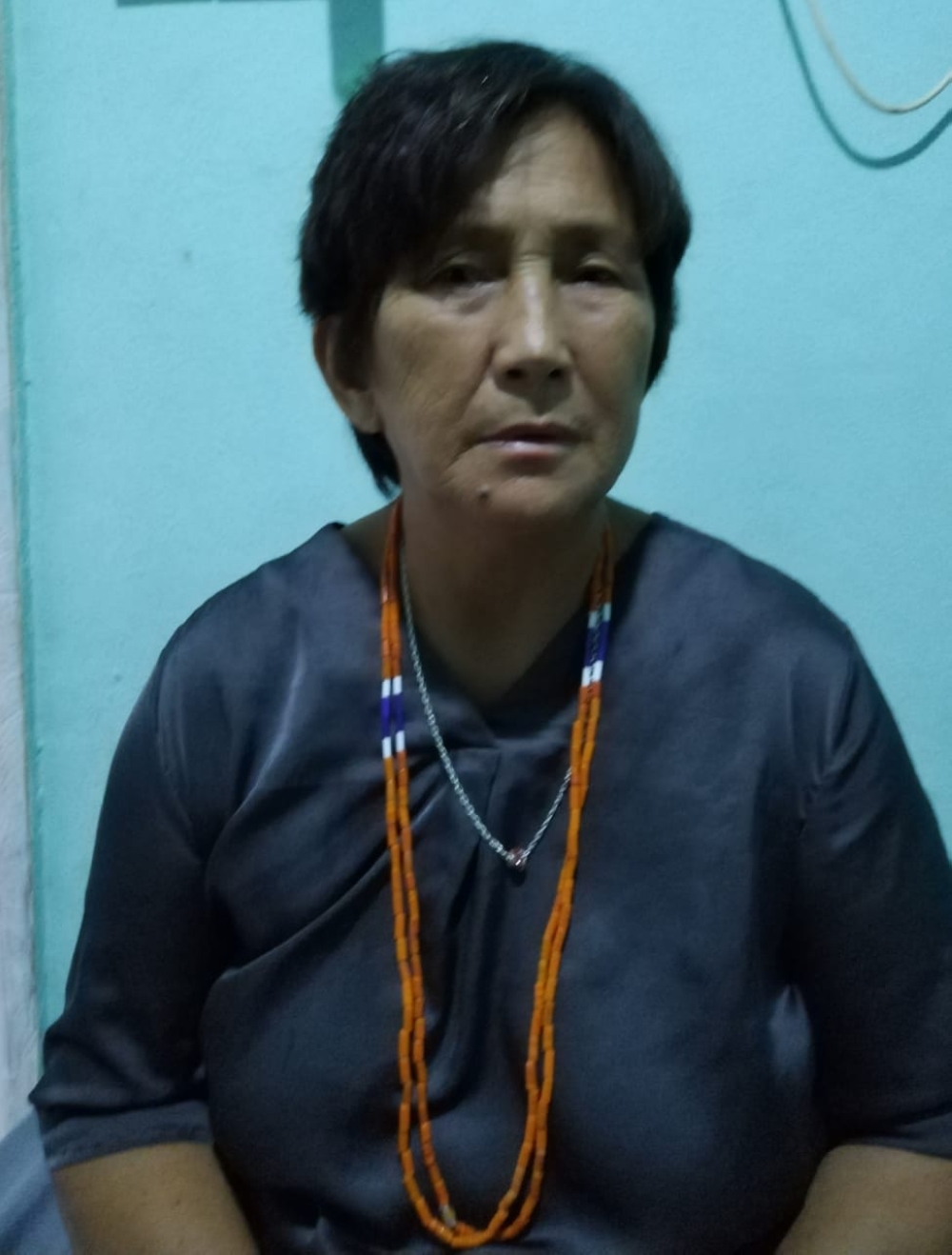

One example is Yana@Anna Daring, a Lun Bawang from Long Tuma in Lawas. She is the eldest of eight siblings, and also the only one who is still stateless in her family.

Lack of documents

Born in 1953 to Malaysian parents, Yana is still fighting over her citizenship status.

She had made repeated trips to NRD over the years, but until this day, lack of documents such as information related to her birth, has prevented her from submitting an official application.

Due to her citizenship status, all her nine children who were born in Malaysia, were only given temporary resident status.

Agnes said some stateless individuals, especially those in their late 70s and 80s, could not prove their place of birth because their parents had passed away.

“Some of them had difficulty to prove their birth because they were born in the jungle, or in the village where there was no clinic nearby. These would usually be the case for those born (in the) pre-Independence (era),” she said.

Meanwhile, Belaweng said there are still a number of Penans from his village who are either stateless, or are holding ‘Permanent Resident’ (MyPR) status.

He blamed the complexity of the procedures for applying for citizenship as one of the main reasons why they are facing this problem.

“Some cannot apply because they have no guarantor, especially the older ones, because their parents and siblings had died. Not only that, but some cannot afford to pay for the transportation charges to bring their guarantors to the NRD offices to support their applications,” he said.

Belaweng said the Penans are also subject to discrimination, and often accused of being Indonesians.

“We are people of the land. We have lived here our entire lives, but sometimes we get accused of being Indonesians.

“Even though many of us have settled permanently in villages, there are still a few Penans who live as nomads in the jungle because they are still scared to come out to the outside world,” he said.

Gaps in citizenship laws

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has stated that gaps in Malaysia’s citizenship laws are a major cause of statelessness in the country.

One of them is Section 17 (Second Schedule, Part III) of the Federal Constitution, which does not allow Malaysian men to pass down their citizenship to their children who are born out of legal wedlock.

UNHCR says apart from Malaysia, two other countries that practicse this are Barbados and Bahamas.

Also, the NRD has been long criticised for prohibiting Malaysian mothers who give birth overseas from passing down their citizenship to their children. — THE BORNEO POST