TOKYO, June 11 — When Megumi Ota needed the morning-after pill in Japan, she couldn’t get a prescription in time under a policy activists call an attempt to “control” women’s reproductive rights.

“I wanted to take it but couldn’t over a weekend,” when most clinics are closed, she told AFP.

Unable to arrange an appointment in the 72 hours after sex when the drug is most effective, “I just had to leave it to chance, and got pregnant.”

Emergency contraception cannot be bought without a doctor’s approval in Japan and is not covered by public health insurance, so can cost up to US$150 (RM660).

It’s also the only medicine that must be taken in front of a pharmacist to stop it from being sold on the black market.

Abortion rights are just as restrictive, campaigners say, with consent required from a male partner, and a surgical procedure the only option because abortion pills are not yet legal.

A government panel was formed in October to study if the morning-after pill should be sold over the counter, like in North America, most of the EU, and some Asian countries.

But gynaecologists have raised concerns, including that it could increase the spread of diseases by encouraging casual, unprotected sex.

Ota decided to terminate her pregnancy after her partner, who had refused to use condoms, reacted coldly to the news.

“I just felt helpless,” said the 43-year-old, who was 36 at the time and now runs a sexual trauma support group.

Japan has world-class medical care but is ranked 120th of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum’s gender gap index, which measures health among other categories.

“In Japan’s system, there’s a perception that women may abuse what they have and do something wrong,” said reproductive rights advocate Asuka Someya.

“There’s a strong paternalistic tendency in the medical world. They want to keep women under their control.”

Limited Choices

The debate comes with reproductive rights in the global spotlight.

In the United States, the Supreme Court appears poised to overturn a 1973 ruling guaranteeing abortion access nationwide, while Poland enacted a near-total ban on terminations less than two years ago.

There are an estimated 610,000 unplanned pregnancies each year in Japan, according to a 2019 survey by Bayer and Tokyo University.

Abortion has been legal since 1948 and is available up until 22 weeks, but consent is required from a spouse or partner. Exceptions are granted only in cases of rape or domestic abuse, or if the partner is dead or missing.

A British pharmaceutical firm last year applied to Japanese health authorities for approval of its abortion pill, which can be used in early pregnancy.

But until a decision is made, those seeking termination must undergo an operation to remove tissue from the womb with a metal or plastic instrument.

The procedure costs around ¥100,000 to ¥200,000 (RM3,275 to RM6,550), with late-stage abortions sometimes even more expensive.

Someya, who had an abortion as a student, said she was “terrified” and wishes she had been able to “choose more comfortably between different options”.

“I was informed of the risk that the operation could leave me sterile, but I thought I would be to blame,” said the 36-year-old, who now views abortion as medical care women deserve access to.

Birth control choices are also limited in Japan, where condoms are by far the preferred method, and alternatives are rarely openly discussed.

Contraceptive pills were approved in 1999, after decades of deliberation by the government — compared to just six months for Viagra.

Nowadays they are used by just 2.9 percent of women of reproductive age, compared to a third in France and nearly 20 percent in Thailand, according to a 2019 UN report.

Meanwhile, IUDs, which sit inside the womb to prevent pregnancy, are used by 0.4 percent while implants and injections are not available at all.

‘We Must Change’

Gynaecologist Sakiko Enmi, a leading member of the campaign for better access to the morning-after pill, said the government must not drag its feet.

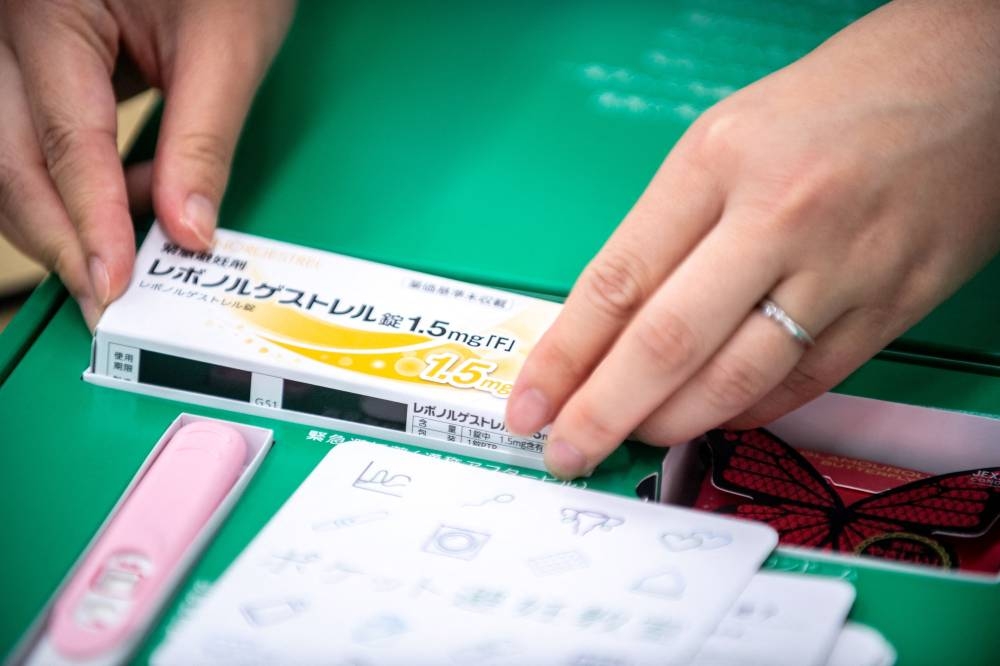

Levonorgestrel, a drug used in emergency contraception to delay or prevent ovulation, has been legal in Japan for more than a decade.

But “it does not reach those who really need it, due to poor accessibility and the price,” Enmi said.

Women can consult a doctor online, but still must take the morning-after pill in front of a pharmacist — Japan’s only medicine that has this requirement as standard, the Tokyo Pharmaceutical Association says.

A previous government panel rejected making emergency contraception available over the counter in 2017, and many medics remain opposed to the change.

In October, a Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists survey found 40 per cent of its members were against the proposal.

Overall, 92 per cent said they had concerns, with the report stating that “this country needs to improve sex education before considering whether to make the emergency contraceptive pill available over the counter”.

Enmi, however, is adamant about what needs to happen.

“We must change,” she said. “Women should be allowed to make decisions for themselves.” — ETX Studio