PETALING JAYA, April 13 — Sivasangaran Kumaran did not think too much of his daughter Swathi Nisha Nair’s quirks as an infant.

The father-of-two, who goes by Siva, noticed how Swathi liked to stick her tongue out, make odd facial expressions, and had delayed developmental milestones.

It wasn’t until she developed pneumonia at the age of six months in 2017 that Siva and his wife discovered a much deeper problem with their daughter’s health.

A chest X-ray revealed that Swathi’s heart was of abnormal size and an echocardiogram showed that her heart was only functioning at a rate of 25 per cent.

Swathi’s doctor also picked up on the symptoms that her parents initially dismissed and performed a gene mutation test on her, which revealed that she had Pompe disease.

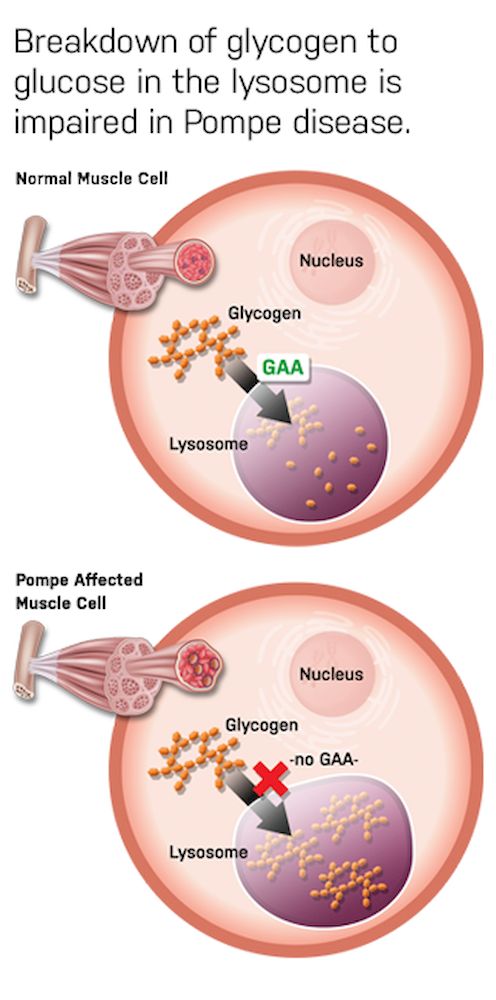

The rare condition, which affects only one in 40,000 people, is linked to a deficiency in an enzyme called acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) which breaks down a form of sugar known as glycogen.

A lack of GAA means glycogen builds up in a person’s cells and damages their muscles, leading to poor physical growth, an enlarged heart, and difficulties in breathing, hearing, talking, and eating in infantile-onset cases.

In an interview with media outlets, Siva said it felt like the family’s whole world came crashing down when Swathi was diagnosed.

“It felt like we were in the middle of a thunderstorm delivering blow after blow of devastating news.

“Eventually, we had to accept the truth and face an impossible decision: to treat Swathi or enjoy whatever time we had left with her and be prepared to say our goodbyes.

“In the end, even knowing that treatment would not guarantee her survival and that her life would be a difficult one, our parental instincts won and we chose to fight for and with Swathi,” said Siva.

RM500,000 a year for treatment

Needless to say, Swathi’s diagnosis turned her family’s life upside down.

Her mother gave up her job in December 2017 to become a full-time caregiver for her daughter, who is now almost four years old.

The loss of income presented an extra hurdle for Swathi’s parents as treating Pompe disease in Malaysia is typically a costly affair.

Siva said that Swathi’s treatment, medication, and therapy can set back the family a whopping RM500,000 every year.

Treatment facilities are not available in Seremban where the family resides which means they have to get up at 4am once a week to travel to Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL) so Swathi can undergo life-saving enzyme replacement therapy.

On top of this, she gets physiotherapy, occupational therapy, aqua therapy, and speech therapy a few times a week to help her reach developmental milestones.

Though Swathi is still non-verbal, her heart and liver functions have improved and she has managed to catch up to her physical milestones thanks to therapy.

A lonely journey

With so many added responsibilities, it’s no surprise that being a parent of a child with a rare disease can be a lonely experience,

Siva says that he and his wife have grown to accept that Swathi’s condition is unique and that it would be difficult for them to find other parents going through the same experience.

“Initially, it was very difficult as we learned that ‘no child is the same even with the same diagnosis.’

“There isn’t another child like Swathi with Pompe, maybe some similarities but there will be major differences.

“That also means limited expertise or knowledge on Swathi’s condition.”

The couple has also faced challenges juggling responsibilities between caring for Swathi and raising her 12-year-old brother Harrish.

Siva confessed that it was difficult to give equal amounts of attention and care to both children as Swathi’s condition forced them to uproot their routines and start anew.

“Before Swathi, Harrish had all the attention and love but this was somehow impacted after Swathi was diagnosed.

“This is hard to explain in words but it’s very difficult to juggle the love and care for a normal child versus a child (with a rare disease) to ensure both their needs are well taken care of without neglecting the other.”

Siva added that he was grateful for Harrish taking everything into his stride and being a loving older brother to Swathi.

He and his wife have also found solace in non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and online support groups on a local, regional, and global level that focus on parents caring for children with rare diseases.

Making peace with uncertainty

While treatment has helped Swathi, her father said that they can never be certain about her future as new symptoms often appear once they have resolved old ones.

It is also unclear how much longer Swathi will respond to therapy and if her family can continue to fork out money for her treatments in the long run.

As a result, Siva and his wife have tuned their mindsets to be realistic about what they can provide for their daughter.

The couple does not have any “major ambitions” for Swathi and is instead focused on letting her live a happy and healthy life for as long as possible.

They’re also working hard to look after themselves in the process so they can be ready for the challenges that lie ahead.

“More than anything, I want Swathi to be healthy, to be able to talk and call me ‘papa.’

“It is incredibly difficult for parents to cope when their child is diagnosed with a rare disease, and they need to receive emotional support and understanding to help them, so they in turn can do what it takes to care for their child,” said Siva.

Tacking delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses for rare diseases

In light of International Pompe Day on April 15, Siva hopes that Swathi’s story can inform Malaysians about the existence of Pompe disease and rare diseases as a whole.

HKL clinical genetics paediatrician Dr Muzhirah Aisha Haniffa said one of the main issues causing delayed diagnoses of rare diseases is a lack of awareness in both the public and medical practitioners.

“It takes an attentive and experienced doctor to recognise signs of Pompe disease.

“For example, infantile-onset Pompe disease is characterised by enlarged heart, difficulty feeding and poor physical growth, which could be attributed to many other common problems.

“Meanwhile, for those who experience symptoms as adults, they typically wouldn’t think that fatigue, weakness in the legs or tripping while walking, and difficulty swallowing are all part of the same problem,” said Dr Muzhirah.

A 21-year-old Malaysian man who wishes to be known as Lee faced this dilemma as he initially chalked up his chest discomfort and abnormal walk to other issues.

It took him six months to reach a conclusive Pompe disease diagnosis, during which he saw five specialists before being referred to HKL clinical genetics consultant Dr Ngu Lock Hock.

Lee’s biggest concern now, just like with Swathi’s parents, is figuring out how to fund his life-long treatments.

“My concern is how much of my funding can cover the cost of the treatment as it is exorbitant.

“Each treatment session is equivalent to the price of a small car,” said Lee.

Dr Ngu said this is a familiar scenario for many rare disease patients due to the myriad of therapies required and the lack of proper treatment facilities in the country.

According to statistics from HKL’s genetics clinic, approximately 20 people were diagnosed with Pompe disease in the last decade.

Due to the small number of patients, treatment options and facilities in Malaysia are extremely limited and research on the disease is even more scarce.

In light of this, a rare disease policy that covers access to treatment and sustainable funding is being developed by the Health Ministry in addition to the rehabilitation and support it currently provides for rare disease patients.

This builds on the recommendations in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) Action Plan on Rare Diseases, which were endorsed by Apec health ministers in 2018.

However, expansion of the current rare disease funding in Malaysia is still needed to ensure patients like Swathi and Lee do not get left behind.

To help individuals and families learn how to manage life with a rare disease like Pompe, the Malaysia Lysosomal Diseases Association and the Malaysian Rare Disorders Society offer education, support, and other resources.

For more information, speak to your doctor or visit https://www.mymlda.com/ or http://www.mrds.org.my/.